By Noah Williams

On 12 July 1884 ‘[t]he announcement of the verdict [in Cornwall v. O’Brien] was instantly carried outside, and the cheers with which it was received by those in court were echoed again and again outside’. When William O’Brien, editor of United Ireland, left the court, it was reported that the ‘crowds who assembled along the precincts of the court and in the courtyard gave vent to a torrent of cheering and applause such as probably has never been heard at the close of any case tried in the four courts’. Cries of ‘Cheers for O’Brien’ and ‘Long live United Ireland’ were reportedly heard all around Dublin city for ridding Ireland of the ‘moral leprosy’ that was homosexuality.

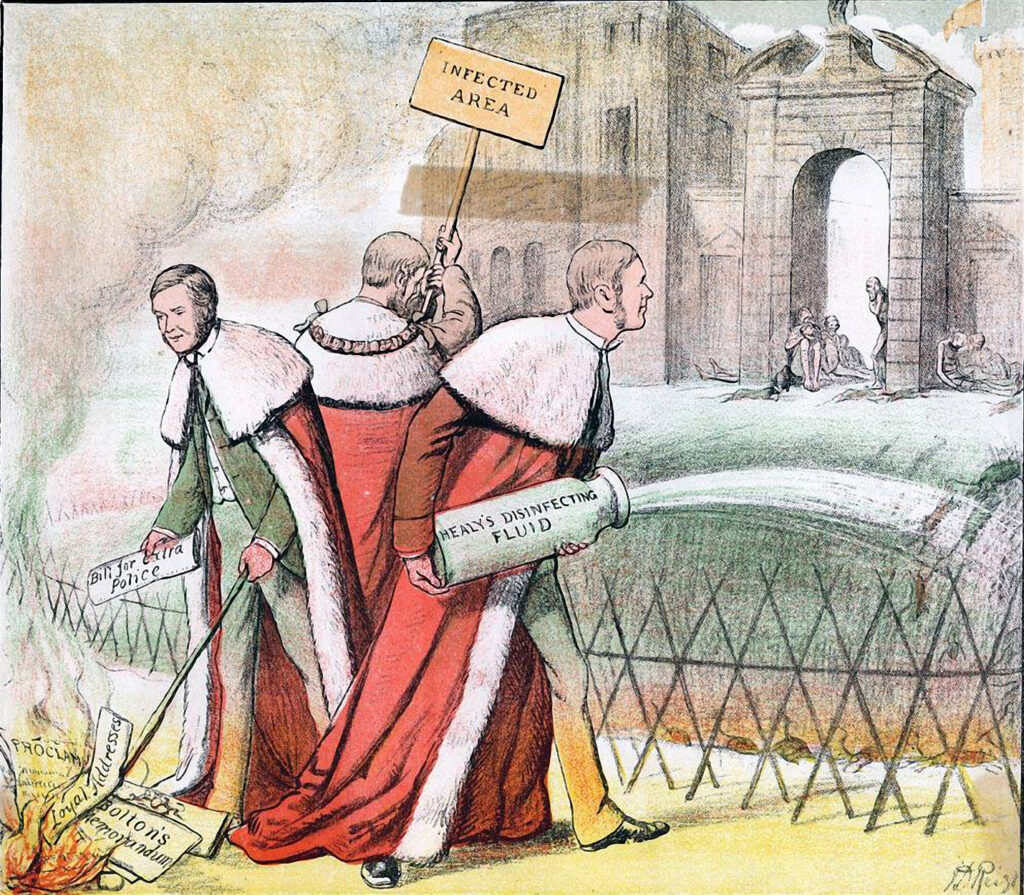

The ‘United Ireland’ or ‘Dublin Castle’ scandal of 1884 arose from the publication of several articles in the United Ireland newspaper that contained allegations of homosexuality amongst representatives of the British administration in Ireland. United Ireland was founded in 1881 by Charles Stewart Parnell, who felt that other Irish newspapers had insufficiently nationalist leanings. It was pro-Home Rule and, as A.G. Cocks notes, was used ‘to constantly needle the British in an effort to undermine their rule, reporting on scandals, raising money for agitators, and organizing like-minded Irish men and women’. The newspaper used homophobia as a weapon to undermine British rule in Ireland by an effort to distinguish Irishness from the morally corrupt English.

In August 1883 United Ireland published stories regarding the sexual inclinations of James Ellis French, director of the detective department of the Royal Irish Constabulary. In May 1884 similar stories were published about Gustavus Cornwall, secretary of the Dublin department of the General Post Office (GPO). At the time, being accused of something like same-sex desire without legally challenging the accuser was as good as an admission of guilt. Consequently, French and Cornwall were lured into libel suits.

LIBEL TRIALS OF JAMES ELLIS FRENCH AND GUSTAVUS CORNWALL

In August 1883 United Ireland published several articles alleging that James Ellis French was at the centre of a network of homosexuals. Although advised against it by another member of the underground community, French sued O’Brien as editor of United Ireland for libel, but he allegedly began suffering from a mental breakdown. This meant that he was unable to pursue his libel claim, which was consequently dismissed by the courts.

In preparation for French’s case, however, O’Brien hired a disgraced former Scotland Yard detective named Meiklejohn to find evidence to substantiate the original publications. Meiklejohn discovered a ‘whole network of gay men who were active in the city’s gay underground’. This was the subject of further articles in United Ireland in May 1884, the focus of which was Gustavus Cornwall of the GPO.

Following these further publications, Cornwall issued proceedings against O’Brien for libel, seeking damages of £10,000. O’Brien planned to prove that Cornwall did commit the acts alleged, namely indecent acts and sodomy. Evidence obtained by Meiklejohn in the form of witnesses who were party to the alleged offences was produced in court. Although Cornwall claimed that there was ‘not a particle’ of truth in the articles, the jury found on the balance of probabilities that the statements made in United Ireland against Cornwall were true in substance and in fact. Cornwall’s action failed because ‘the law will not permit a man to recover damages in respect of an injury to a character which he either does not, or ought not, to possess’.

Following the witness testimonies in the libel actions, many others were implicated in the scandal. The articles unleashed a wave of defamation actions and criminal prosecutions, resulting in the uncovering of a clandestine network of homosexual men in Victorian Dublin.

CRIMINAL TRIALS OF GUSTAVUS CORNWALL AND MARTIN KIRWIN

On 30 September 1884 Cornwall was arrested and committed to Kilmainham Gaol. He was indicted alone on one felony charge and was also indicted alongside Captain Martin Kirwan of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers (a cousin of Lord Oranmore) on six non-felony counts. An example of one of the charges was:

‘… being lewd and evil-disposed persons, and wickedly devising and intending to debauch and corrupt young men, did among themselves … agree to procure young men and boys … to commit with the said [Cornwall] and [Kirwan] certain filthy, lewd, and indecent acts, amount to and being outrages on decency and morality’.

The jury in Cornwall’s and Kirwan’s case struggled to reach a verdict and were subsequently discharged. The divisive point was the question of the credibility of witnesses, all of whom were also accomplices.

In criminal trials of this nature there were specific evidential burdens to ensure that individuals were not wrongly convicted of crimes which were, or were considered to be, of a most serious and grave nature. Proving such an offence was done through two methods—either by evidence of a witness who spied on the offence, or by persuading the other party (an accomplice) to act as a witness. This was the more common approach, given the difficulty of providing a non-participating witness to the offence. A criminal rule of evidence was later established in the mid-eighteenth century that where evidence was given from such an accomplice there needed to be independent corroboration. For example, in the Oscar Wilde trial, evidence given regarding the state of the bedding in the hotel room by a maid was used to corroborate evidence given by an accomplice. If there was no such corroboration, judges had to instruct the jury that they should consider evidence from an accomplice with great scepticism or, alternatively, that convicting on the basis of evidence from an accomplice was ‘unsafe’.

Another difficulty was that Cornwall and Kirwan had been charged with conspiring together and therefore the judge’s charge to the jury stated that they had to convict or acquit both. The jury were unable to agree on whether Cornwall and Kirwan had conspired together; they only wanted to find Kirwan guilty. Failing to reach agreement, they were discharged.

There were further weaknesses in the Crown’s prosecution. In the felony case solely against Cornwall, evidence was given by William Clarke, a man in his late twenties. Clarke, who was seemingly a male prostitute, gave evidence that he was sometimes given money for sexual favours but he never sought payment. John Monroe QC, addressing the jury on behalf of Cornwall, stated that ‘everyone would be amazed that a man in the position of Mr Cornwall was put on trial on the evidence of such abandoned wretches as Clarke’. He further commented that, ‘if such a course was pursued by the Crown, no man’s liberty would be safe’. Evidence was also given that Cornwall was in Scotland at the time when the offences were alleged to have taken place. On 21 August 1884, following a six-minute deliberation, the jury acquitted Cornwall on the felony charge.

Undeterred by these failures, the Crown tried Cornwall and Kirwan on different offences: conspiring to procure the commission of ‘unnatural offences’. The result of this trial was that both were found ‘not guilty’, as the Crown evidence was insufficient. Witnesses for the prosecution admitted in cross-examination ‘that Detective Meiklejohn induced them to give information’. In his charge to the jury, the judge advised that if the witnesses for the prosecution ‘were not accomplices they were certainly tainted witnesses, who had unblushingly admitted the wretched lives they had lived. But at the same time it was quite possible for people steeped in crime to tell the truth, and it was for the jury to decide that point in the case.’ He told the jury that they had to ‘take into consideration the vile lives the two witnesses admitted they had lived. They would have to ask themselves could they base a verdict of guilty on the testimony of such criminals as the witnesses.’ Following a twenty-minute deliberation by the jury, the defendants were acquitted.

Although acquitted, Cornwall lost his libel trial and suffered serious damage to his reputation and social rank. He was forced to retire early from the GPO without a pension after 45 years of service.

CRIMINAL TRIAL OF JAMES ELLIS FRENCH

In July 1884 French was charged that he on several occasions committed the felony of buggery, and also that he attempted to commit such a felony. It was also alleged that he solicited and incited for the purposes of committing buggery, and that he conspired with others to procure persons to procure the commission of buggery. He was also indicted on charges of attempting to commit sodomy with Clarke, the same man who gave evidence against Cornwall and Kirwan.

French was eventually convicted of the misdemeanour of conspiracy to commit buggery after his sanity was upheld by a special jury. After the jury delivered their verdict, the judge, Mr Justice O’Brien, said to French: ‘You have lost everything by your own crime—your position, your reputation and character, and your liberty’. As French was an officer of the law, and ‘bound by a higher more solemn engagement than the rest’, he could not award him ‘any less sentence than the extreme penalty of the law’. He was sentenced to two years in prison with hard labour.

WEAPONISATION OF HOMOPHOBIA

United Ireland’s successful campaign to ruin French and Cornwall is a perfect case-study of the use of homophobia in the nationalist movement in Ireland. As Averill Earls notes, ‘the politicization of same-sex sex in Irish nationalist papers is most illustrative of an Irish anticolonialism effort to draw a line between Irishness and Englishness’. United Ireland and other nationalist newspapers reported on scandals of same-sex relations in their newspapers in order to depict the English as morally corrupt, aiming to undermine British rule in Ireland. The idea was that Irish purity could only be preserved through Irish rule.

The link between homosexuality and British rule was explicitly made in an article in United Ireland on 12 July 1884, following the verdict in Cornwall’s libel trial. United Ireland quoted the Freeman’s Journal, stating:

‘We will not be stupid or unjust as to say that there is any necessary connection between such crimes as Mr Cornwall has practically been found guilty of and the system of British rule in Ireland. It is, however, justifiable to note, as a well-known historical experience, that despotic forms of government and odious vice have had in the history of the world an association so common as to be justifiably held as cause and effect. The reigns of autocrats have, from the days of the first Roman Emperors to those of the last Napoleon, been remarkable for the growth in rank luxuriance of all forms of unnatural vice, and the same cause which produced these effects in Rome and Paris may be inferred to have been the parent of the same effects in Dublin.’

The lasting effect of this portrayal of the English as a morally corrupting influence persisted long after independence. While marching with the Irish Gay and Lesbian Organisation during the St Patrick’s Day parade in New York in the 1990s, David Beriss notes seeing an old woman holding up a sign which read: ‘If you’re gay and you’re Irish your parents must be English’.

HOMOSEXUAL LIFE IN VICTORIAN IRELAND

The underground homosexual community uncovered by the ‘United Ireland scandal’ highlights some aspects of life in Victorian Ireland that have not commonly been associated with this period of Irish history. A seemingly small, close-knit homosexual community existed, which grew through mutual connectors like Cornwall; this community was involved with the theatre, hosting musical and theatrical parties—for example, a ‘drag ball’ where many of the men in attendance dressed as women, taking up nicknames. It is even reported that this ball was attended by ‘at least one clergyman from both of the main churches’. The men also enjoyed walks in the Botanic Gardens and the Phoenix Park together and attended flower shows and concerts in the Royal Irish Academy.

The life of a homosexual involved in this underground community and subculture in many ways depicts Victorian Dublin as a more cultural and modern city than commonly thought. Nevertheless, it should not be considered in a wholly positive light. The surviving witness testimonies used in the prosecutions also show a litany of allegations of sexual exploitation and sexual harassment, especially by older wealthier men on younger men. Instances of rape, sexual assault and sexual harassment went unreported and seemed to be a normal part of homosexual life in Victorian Dublin. One particularly dark allegation was made by Clarke, describing an interaction with French:

‘He forced me to take down my trousers, and I did. He dragged me about and pressed me very much to him and forced his person into me, after I had turned my back to him, and hurt me very much. I screamed. … It was forcibly, against my will.’

Clarke went on to say that he ‘was then about sixteen years old’, and that he ‘roared about so much that [French] made me take up my trousers’. Yet no complaint was made by Clarke to the authorities. Owing to the forced underground nature of such a life in Ireland at that time, and for long after, there was no protection or potential redress afforded to victims of such crimes.

Noah Williams is a UCD law graduate, currently studying for an LL.M in the University of Edinburgh.

Further reading

A. Earls, ‘Unnatural offences of English import: the political association of Englishness and same-sex desire in nineteenth-century Irish nationalist media’, Journal of the History of Sexuality 28 (3) (2019), 396–424.

R. Norton (ed.), ‘The Dublin scandals, 1884’, Homosexuality in nineteenth-century England: a sourcebook (www.rictornorton.co.uk).

‘R v. Gustavus Cornwall’, August 1884: Box 15, Crown & Peace Files, 3-045-14, City and County Dublin, National Archives of Ireland.

N. Williams, ‘Nationalism, homophobia and a Victorian Dublin subculture’ in UCD Law Review(2024).

This is an edited version of the undergraduate winner of the 2024 Irish Legal History Society student essay prize. Further information: https://www.irishlegalhistorysociety.org/?page_id=1464.