By Robert Delaney

September 2025 marks 100 years since the Irish army first fired artillery in the Glen of Imaal. It was the beginning of the Artillery Corps’ long association with the Wicklow training ground, and it defined the Defence Forces’ approach to artillery exercises for decades to come. The Artillery Corps was established officially on 23 March 1923, two months before the end of the Civil War. It had nine 18-pounder field guns and 62 ‘stout-hearted prospective gunners’. The guns were those supplied by the British during June and July 1922; the ‘prospective gunners’ were the men who operated them when they were deployed across the country during the conflict. The Free State’s eagerness to use artillery against the anti-Treaty side from the start of the war meant that these gunners earned the unique distinction of firing their weapons in combat before firing them on a practice range. In fact, it took three years to get to the range. The Artillery Corps’ commanding officer, Patrick Mulcahy, explained: ‘We had guns, and we had knowledge, but we couldn’t start shooting practices until the ammunition arrived’. Contemporary army files confirm that there were major problems in obtaining ammunition, but the corps also had to deal with shortages of equipment and, more importantly, the men needed training to gain the knowledge that Mulcahy mentioned.

HORSES

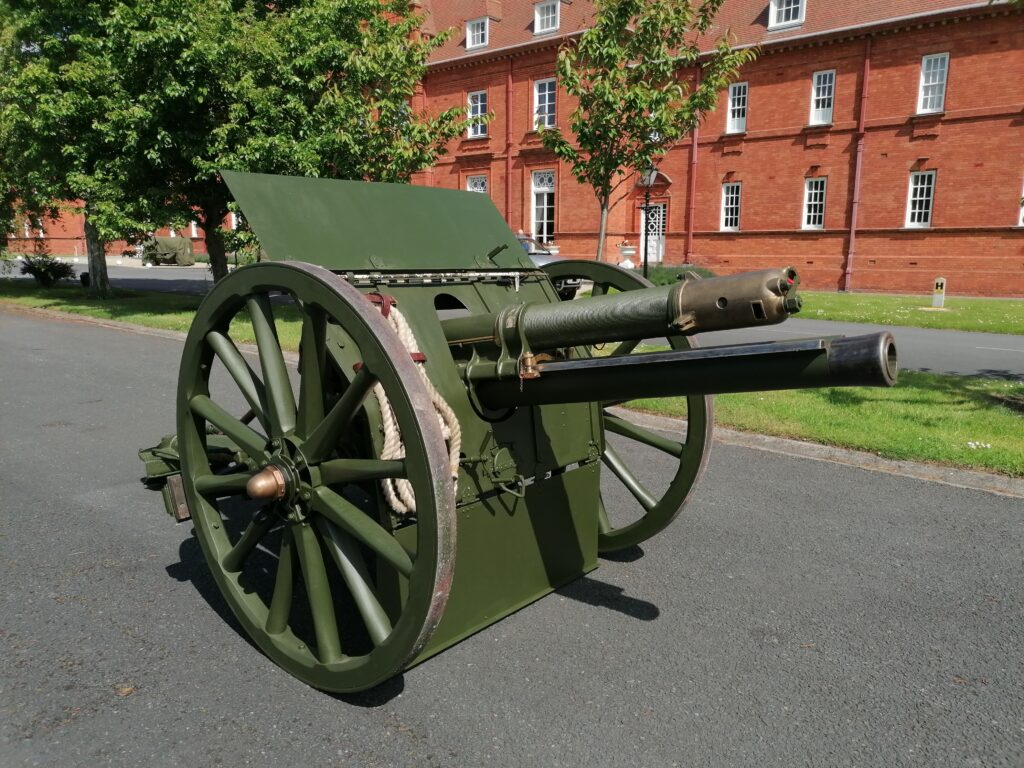

When Mulcahy was given command of the Artillery Corps in 1923, he made it clear to the chief of staff that he knew nothing about artillery, only to be told ‘Neither do any of us!’ During the Civil War, the 18-pounders were sometimes used in the most rudimentary, even crude, way and the term ‘gunner’ could only be applied loosely to the men behind the weapons. An intense period of training began that summer for everyone ‘from the Officer Commanding down to the latest recruit’. It was perhaps unsurprising that some of the men who had previously served with the guns proved unfit for service in the new corps. Horsemanship training started; the use of lorries to pull the guns during the previous year was unconventional, and the Artillery Corps, like the Royal Artillery, would use a team of six horses to haul each 18-pounder. While the unit was based in Marlborough (now McKee) Barracks in Dublin, the Fifteen Acres in the Phoenix Park were ideal for exercising men and horses. They learned quickly: as early as June 1923 a reporter watched a battery of four guns ‘sweeping over the grass, wheeling and circling … then at the command “Halt! Action Rear!” … the horses, unlimbered and moving off, leaving the gun ready for action’.

SHORTAGE OF EQUIPMENT

Gunnery was a separate skill that took about six months to master. It was taught first in the barracks, and when the unit moved to Kildare in 1925 the Curragh plains became the training ground. Officers learned the basics before they were introduced to the various roles that a lieutenant might be assigned in the gun battery. The opportunity to train with artillery schools abroad was still three years away, so Mulcahy sought expert help wherever it was available; the Ordnance Survey Department in the Phoenix Park was consulted about lessons in trigonometry and the use of survey instruments. This, however, highlighted another problem: the shortage of equipment. The artillery at this stage lacked many of the instruments that were required to position a battery correctly and to calculate and direct its fall of shot accurately. Barometers, rangefinders and directors were only procured six months after the first shot was fired.

A huge amount of equipment was required across the army and all kinds of artillery stores and munitions were purchased from the British War Office (WO) during these early years, but the procurement process was slow. An advance of £137,000 paid to the British in March 1925 failed to speed things up and the Free State had to follow the same procedures as the ‘dominion and colonial governments’ when placing an order. On the Irish side, a request for equipment passed through a succession of army offices before going to the Department of Defence, and every purchase had to be sanctioned by the Department of Finance before it was sent to the newly installed high commissioner in London, who eventually passed it on to the WO. It could take months, or even years.

Nevertheless, by May 1925 one 18-pounder battery had been trained to an acceptable standard and was ready to fire on the range. A second battery formed that January was in training, and ‘officers, NCOs and specialists’ were to go to the Glen of Imaal for a short course during the summer. It was a significant achievement but there was to be one more delay—a shortage of ammunition. The army had a stock of 18-pounder rounds that had been supplied by the British during the Civil War. When these were inspected by an ordnance officer in October 1924 they were found to be in a bad state. The officer was convinced that the poor condition of the ammunition demonstrated that there was ‘considerable indifference as to the quality of the shells when handed over’, and he believed that they were only accepted because of ‘the exigencies of the times’. Some of the problems might be explained by the 1917 manufacture date. Wartime munitions’ production was at a peak that year; 300,000 shrapnel shells were being produced every week, and a shortage of materials was causing ‘unsatisfactory deliveries’, but the Irish ammunition did not conform to the conditions laid down in the British Ordnance Regulations.

Surprisingly, things moved quickly after this discovery and the Department of Finance sanctioned the purchase of 1,000 rounds before the end of the year. The initial response from the WO indicated that the ammunition was available, though it was cutting it fine to have it delivered in time for the 1925 training period. Then three months later a letter from the WO explained that the Irish demand for the most up-to-date version of the shrapnel shell could not be fulfilled, as there were none in stock. They could be manufactured, but this would take time; in the meantime, 200 ‘older pattern’ shells could be supplied. These were ‘fully serviceable’, according to the WO, and were ‘being used and are likely to be used for some years to come by the British army’. It was agreed to accept these rounds instead, but at this point Mulcahy must have accepted that it was unlikely that the guns would fire that summer. Undeterred, he made preparations to occupy Coolmoney camp in the Glen of Imaal.

GLEN OF IMAAL.

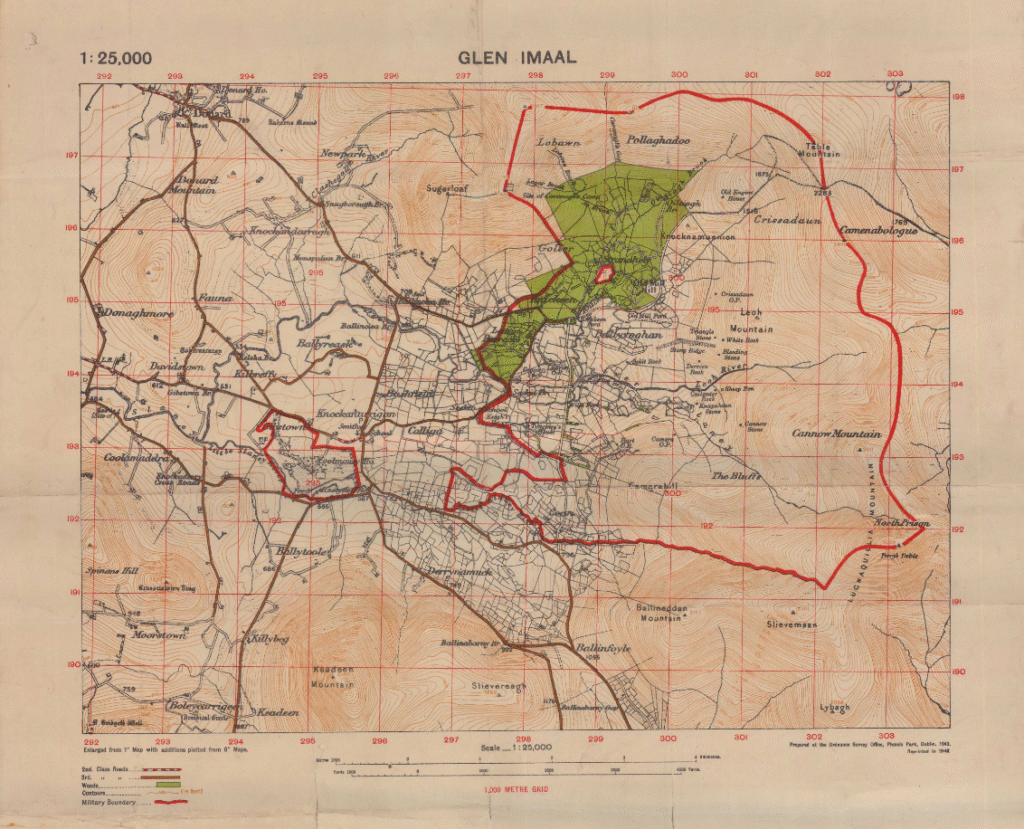

The Glen of Imaal had been used by the British for artillery training since 1899. The camp there was large enough to accommodate three 18-pounder batteries—about 350 soldiers and 150 horses—and the valley beneath Lugnaquilla mountain made an ideal shooting range for artillery. The Royal Artillery had built splinter-proof bomb shelters and laid armoured cables to establish communications between observation dugouts and firing-points, and before the camp was abandoned by the British in February 1922 improvements had been made to a moving-target system. The harsh landscape made gun-towing difficult, and gun detachments were challenged as they took ‘their team [of horses] and guns through places which try their patience, coolness, efficiency and daring’. Every artillery exercise in ‘the Glen’ commenced with the twenty-mile march from Kildare Barracks, which took the best part of a day. Guns, limbers and supply wagons were all horse-drawn; regular stops were required along the way to water the animals, and ‘a halt’ at Dunlavin allowed time to feed and rest horses and men. In Coolmoney the camp was basic; it had not been occupied since it was dismantled by the army’s Salvage Corps during the Civil War. The officers’ mess was in the main building, Coolmoney House, which needed ‘slight repairs’, but the men were under canvas and temporary wash-houses, latrines and horse troughs had all to be erected by army engineers.

No. 1 gun battery occupied the camp first in July 1925. By then it was the better trained of the two and was armed with four 18-pounder Mark II field guns, the first that were handed over by the British in 1922. These were slightly more advanced than No. 2 battery’s older Mark I guns and were almost certainly in better condition. It would become the norm in the years that followed for the two batteries to take it in turns to occupy Coolmoney, each for a three-week period, but in the summer of 1925 artillery men spent longer there repairing and improving the camp. A few days before marching to Wicklow, No. 1 battery was on ceremonial duty at Bodenstown. The annual Wolfe Tone commemoration was one of several events that became part of the Artillery Corps’ yearly schedule and helped to familiarise the public with the new peacetime army. No. 2 battery would interrupt its training in August to take part in another of these events, the Griffith/Collins commemoration in Dublin. The strict discipline and attention to detail that the corps valued so much was on display on these occasions, and the diverse nature of its workload was demonstrated by the appearance of horses and men hauling guns through rivers and over mountains a few days after they had been on parade and ‘with all the fittings of the guns burnished to perfection, came in for the lion’s share of admiration’.

FURTHER DELAYS

Army files indicate that the long-awaited supply of 18-pounder ammunition did not arrive for the shoot in September, and the finance officer’s frustration is evident in his letters to the WO. The quartermaster general was still wondering where his ammunition was that November, and it is unclear where the rounds fired during the exercise came from. The condition of the Irish stock of shells may have been reassessed by the Ordnance Service after a delivery of special tooling allowed technicians to strip the rounds and inspect them more thoroughly. This idea is supported by a hastily drafted note written before the shoot that directed ordnance personnel to examine ‘200 shells’. It is likely, too, that the realisation that the British were still firing ‘older pattern’ rounds—as old as the Irish stock—alleviated some of the doubt about using the shells from 1917.

At 10am on 1 September the honour of firing the first shot from an Irish artillery piece in peacetime was given to Major Mulcahy. The significance of the event was described by one correspondent who watched as ‘the hills which had so long echoed to the rumble of the British guns now threw back the echoes of Ireland’s artillery’. A single 18-pounder logbook, known as a ‘history sheet’, survives from the nine ‘Civil War guns’ and it records that one gun fired 43 rounds over six days on the range. The low rates of fire can be explained by the corps’ inexperience and, crucially, by its inaugural introduction to range safety drills. The actions of the gun detachment had to be scrutinised and the aim of the gun checked every time a new target was selected. The highlight was the demonstration on 11 September for Minister for Defence Peter Hughes and Minister for Finance Ernest Blythe, who were joined by senior army staff. Blythe’s attendance was noteworthy; it allowed him to see what his department was spending money on. The battery’s four guns fired probably ten rounds each in a short space of time at targets that were placed on the hillside 5,000 yards away to simulate entrenched enemy troops. The gunnery was impressive enough to bring the minister for defence back the following year along with President of the Executive Council W.T. Cosgrave.

Throughout the 1920s and ’30s the Artillery Corps returned to the Glen of Imaal every summer for training and firing practice. In 1926 Lieutenant Charlie Trodden travelled to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, the US Army’s Field Artillery School. He was the artillery representative on the famous military mission to the US and was the first artillery officer to travel abroad for training. Soon after, Mulcahy went on the battery commander’s course in England, establishing a link with the Royal Artillery’s training school at Larkhill that continues to this day. Many more officers and NCOs have followed in his footsteps, advancing the Artillery Corps’ capabilities and developing its tactics, techniques and methods of training. When Mulcahy came back from Larkhill, he brought plans for an anti-tank range that included a simple moving-target system, and this was subsequently constructed in the Glen of Imaal. More guns (18-pounders Marks IV and V and 4.5in. howitzers) were purchased during the 1920s but there were always difficulties in procuring ammunition. When war broke out in 1939, firing was restricted, as ammunition was stockpiled for defence, but the dire need to qualify gunners for the expanding Artillery Corps saw shooting resume and it peaked with an impressive 72-gun range practice in 1944, probably the largest in the history of the range. This was the last time the ‘Civil War 18-pounders’ were fired. To this day the Glen of Imaal continues to echo to the sound of the Artillery Corps’ guns.

Robert Delaney is an artificer in the Defence Forces and has researched the 18-pounder field gun and its Irish service at Maynooth University.

Further reading

T. Clonan (ed.), Artillery Corps 1923–1998 (Dublin, 1998).

J.P. Duggan, A history of the Irish army (Dublin, 1991).

M. McLoughlin, Kildare Barracks, from the Royal Field Artillery to the Irish Artillery Corps (Sallins, 2014).

R.A. Riccio, The Irish Artillery Corps since 1922 (Poland, 2012).