Religious homogeneity helped contribute to the relative political stability in the Irish Free State during the 1920s. Politico-religious rivalry in the North on the other hand was a major cause of endemic sectarian tension. There were 3,171,697 Catholics living in Ireland, according to the 1926 census — 2,751,269 in Saorstát Éireann [Irish Free State] and 420,428 in Northern Ireland. There were 164,215 members of the Church of Ireland in the Saorstát, 32,429 Presbyterians, 10,663 Methodists, 3,686 Jews, 717 Baptists and 9,013 ‘others’, a total of 220,723 non-Roman Catholics.

Legitimacy of the state reinforced

Irish Catholicism in the 1920s sought, as one of its major objectives, to reinforce the legitimacy of the new state. The post-civil war political climate of Saorstát Éireann suited and reassured members of the Catholic hierarchy. They had lived through the dangers of the war of independence period between 1919 and1921, witnesing the breakdown of law and order. A number of the hierarchy had even found their very lives threatened by elements in the British forces. The killing of three priests demonstrated that the clergy were not immune from the official government policy of reprisals during the ‘Troubles’. Before the signing of the Truce on 9 July 1921, the majority of the Catholic hierarchy had shifted to a political position of tacit support for the constitutional wing of Sinn Féin. They supported the opening of peace talks with the British government and welcomed the signing of the Treaty on 6 December 1921. With the outbreak of civil war in 1922, the hierarchy sided with the Saorstát and roundly condemned the anti-Treatyites in a joint pastoral issued in October 1922.

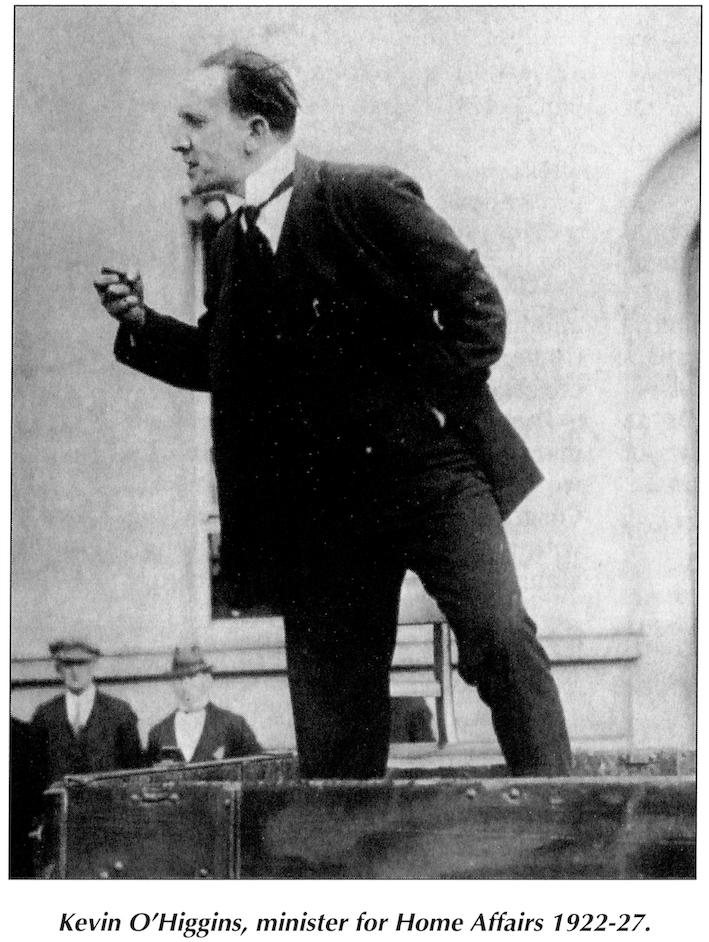

William T. Cosgrave was the President of the Executive Council between 1922 and 1932; he was a devout Catholic and a close friend of the Archbishop of Dublin, Edward Byrne. During the war of independence, he had put forward the idea of establishing a ‘theological senate’ — an upper house for Dáil Éireann in which the Catholic bishops would sit to adjudicate on the orthodoxy of all legislation. But he did not seek to implement that idea when he took office in August 1922. In his personal life he was genuinely devout. He was given special permission from the Holy See to have an oratory built in his home where Mass could be celebrated. The Vice-President and Minister for Home Affairs, Kevin O’Higgins, was an ex-seminarian who had studied for the priesthood in Maynooth. The Minister for Finance, Ernest Blythe, was the only non-Catholic. However, it is important not to overstate this point. While the Cumann na nGaedheal ministers were quite distinctive in their political approaches — and the tensions between personalities was at times very pronounced — there was a tendency to reach consensus easily on church-state questions. The main objective of Cumann na nGaedheal was to strengthen the popular legitimacy of the new Irish state.

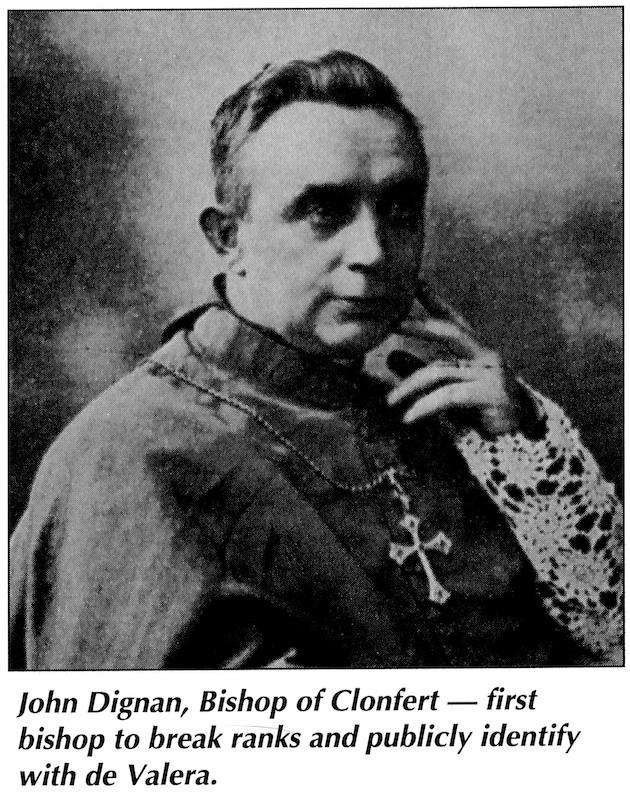

Even if there is evidence that the bishops supported Cosgrave and his party in government, the hierarchy was not Cumann na nGaedheal at prayer. John Dignan of Clonfert was the first bishop to break ranks and publicly identify with de Valera’s anti-Treatyites. As his episcopal ordination in June 1924, he predicted that ‘the Republican Party is certain to return to power in a short time’, a prediction realised in 1932. In the meantime, church and state worked in close harmony with little evidence of conflict.

Moral laxity frowned upon

There was general political approval for the hierarchy’s censorious attitude towards alleged sexual immorality in the Saorstát. The bishops frowned upon modern dancing and foreign fashion fearing that the moral laxity associated with Britain and the continent might reach Irish shores through the medium of cinema, radio and the British yellow press. Archbishop Harty of Cashel said on 25 April 1926 that the ‘quantity of such horrible papers circulating in the country was simply appalling’. On 9 May 1926 Archbishop Gilmartin of Tuam condemned foreign dances, indecent dress, company-keeping and bad books. He spoke of a ‘craze for pleasure — unlawful pleasure’. He warned that family ties were weakened and in other countries where there were facilities for divorce ‘the family hardly existed’. The hierarchy believed that native dancing had salutory powers: ‘Irish dances do not make degenerates’. Sex was, therefore, a matter of considerable concern to church and state alike in the 1920s.

However, legislative initiatives on censorship, the curtailing of drinking hours and illegitimacy were not taken under pressure from the bishops. The Censorship of Films Act was passed in 1923; the Intoxicating Liquor Act was passed in 1924 and amended in 1927; the Censorship of Publications Act became law in 1929 and the Legitimacy Act in 1930. Bishops and politicians shared a conservative Catholic outlook which was also shared, in the main, by the leaders and members of other churches. The government sought the advice of the hierarchy and was usually decisively influenced either by the Archbishop of Dublin or by the bishops as a body.

Divorce

The question of divorce revealed a pattern of relations between church and state which was to repeat itself in the 1930s. Before 1922 a divorce was obtained by private bill in parliament. Soon after independence, three private divorce bills were introduced. The Attorney General, Hugh Kennedy, sought a decision from the Executive Council as to whether legislation would be promoted to set up the necessary procedures. Cosgrave sought the advice of Archbishop Byrne and the bishops as a body. The hierarchy meeting in October 1923 stated ‘that it would be altogether unworthy of an Irish legislative body to sanction the concession of such divorces, no matter who the petitioners may be’. Cosgrave took note and standing orders were suspended to prevent such a bill being introduced into the Dáil. Despite spirited opposition, the measure was upheld. Professor William Magennis summed up the contradictions in the debate: ‘You cannot be a good Catholic if you allow divorce even between Protestants’. There the matter rested until the introduction of Bunreacht na hÉireann in 1937.

Censorship

Since the foundation of the state, the Catholic Truth Society and a number of prominent clergymen had campaigned for stricter censorship laws. The Minister for Home Affairs, Kevin O’Higgins, set up a Committee of Enquiry on Evil Literature 1926. A Censorship Bill was introduced in summer 1928. Leading Irish literary figures, William Butler Yeats, George Bernard Shaw and George Russell all condemned the legislation. But their collective wrath and reputation were not sufficient to prevent the passage of the bill and the first censorship board was established on 13 February 1930. The committee had the power to prohibit the sale and distribution of ‘indecent or obscene’ books. The publishing, selling or distribution of literature advocating birth-control was also deemed an offence under the Act.

Theatre in the Saorstát in the 1920s enjoyed freedom from censorship. However, when the Abbey Theatre performed Sean O’Casey’s The Plough and the Stars, there were vocal protests against the bringing of the tricolour into a public house and to the presence there of a prostitute, Rosie Redmond. The play ran for two weeks but with the lights on in the theatre and with gardaí lining the passages at the sides of the pit. Conservatism remained a feature of most aspects of Irish administrative, cultural and social life in the 1920s. The emphasis was on the need for continuity and conformity.

Education

Economic stringency, the close relationship of the government with the Roman Catholic Church and a state philosophy of minimal interference have been identified as three constraining factors on the development of educational reform in the 1920s where the main emphasis was on curriculum rather than structural change. The Minister for Finance, Ernest Blythe, cut national teachers salaries by 10 per cent in 1923. This reflected the poverty of the country at the time. However, despite the limited state resources during their respective tenures, the two ministers for education Eoin MacNeill (1923-1925) and John Marcus O’Sullivan (1926-1932) were responsible for significant administrative initiatives. The department was created and its procedures established; systematic investigations were launched into various issues; a new secondary examination and curricular structure was devised; a primary certificate was introduced; a network of preparatory colleges was established; and legislation was successfully promoted on school attendance, the universities and vocational education. The Cumann na nGaedheal government established a model which the education system followed with minor modifications for almost forty years. The Catholic church played the central role in the development of a denominational educational system. The Church of Ireland was also provided with a separate primary and secondary school system and separate teacher-training facilities. The Jewish community operated schools in Dublin. The educational system was based on the religious pillars in the state. Through their involvement in education, the churches played a major role in the building of national character and identity.

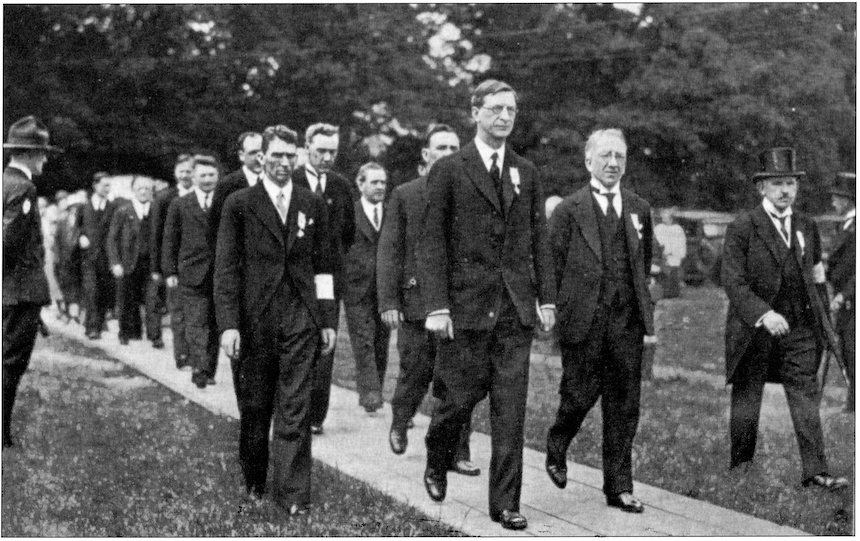

Eamon de Valera: Catholic nationalist

Eamon de Valera, an abstentionist in Irish constitutional politics since the acceptance of the Treaty in 1922, founded Fianna Fáil in 1926 and broke with his more intransigent Sinn Fein colleagues. He entered the Dáil in 1927 and led the opposition until Fianna Fáil was returned to power in 1932. De Valera was a Catholic nationalist. Temporarily out of favour with the Irish hierarchy since 1922, he had managed to restore his credibility among the younger Irish clergy by the late 1920s. Although he had never been perceived as a ‘gunman’ by the bishops, de Valera was held responsible for his poor judgment which had contributed to the outbreak of civil war in 1922. But collective episcopal hostility had waned towards ‘the chief’ by the time Fianna Fáil entered the Dáil.

There was, however, a rump of the hierarchy who neither forgave nor forgot. But members of the hierarchy were, in the main, pragmatists. De Valera was somebody with whom they might soon have to work in government. The arrival of Fianna Fáil in Dáil Éireann placed Cumann na nGaedheal under considerable political strain. Taking stock of its situation in 1929, it made a successful attempt to establish diplomatic relations with the Holy See that year. Paradoxically, this complicated relations between the hierarchy and the government. The bishops were very unhappy at the idea of having a nuncio resident in Dublin. Firstly, they feared that he would be running with tales to Rome all-too-frequently. Secondly, they believed that the nuncio might interfere with the process of episcopal appointments. Thirdly, they believed that British influence would be extended over the Irish church as a consequence of the perceived subservience of the Holy See towards the Court of St James.

The Dunbar-Harrison case

The government survived that storm. But the nuncio crisis of 1929 had given Fianna Fáil an opportunity to demonstrate that Eamon de Valera was more sensitive to the feelings of the hierarchy on that matter than was Cumann na nGaedheal. The vulnerable position of the government also made it amenable to episcopal representations when the Legitimacy Act (1930) was being drafted. That legislation was strongly influenced by canon law. The Vocational Education Act (1930) was also drafted with a view to placating the hierarchy. However, all Cosgrave’s careful efforts not to alienate Protestant opinion was jeopardised by the Letitia Dunbar-Harrison case in 1930. After winning an open competition she had been appointed to the post of librarian for Mayo. She was a Protestant and an honours graduate of Trinity College, Dublin. When the local library committee refused to give approval to the appointment — a stand supported by the local county council — the government stood by the decision of the Local Appointments Commission, disbanded the council and kept Dunbar-Harrison at her post. Local clergy were outspokenly against her appointment. A Christian Brother M.S. Kelly argued that ‘her mental constitution was the constitution of Trinity College’. Mgr D’Alton of Tuam told the local library committee that they were not appointing a ‘washerwoman or a mechanic but an educated girl who ought to know what books to put into the hands of the Catholic boys and girls of this county which was at least 99 per cent Catholic’.

The Catholic-Protestant communities had been driven further apart by the Lambeth Conference decision in 1930 on contraception. D’Alton stressed the difference between the two churches on birth control: ‘supposing there were books attacking these fundamental truths of Catholicity, is it safe to entrust a girl who is not a Catholic, and is not in sympathy with Catholic views, with their handling?’, he asked. These comments echoed the profound mistrust that existed in 1930 at official level between the Protestant and Catholic churches.

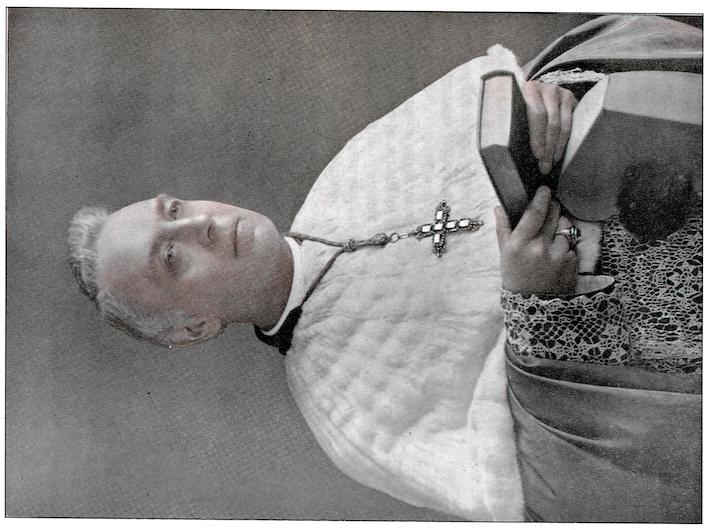

The appointment of Dunbar-Harrison as librarian was really only a minor concern in comparison to the fears expressed in certain Catholic journals about the employment of Trinity graduates as dispensary doctors. The Catholic Bulletin — never regarded by the bishops as automatically reflecting the views of the hierarchy — spoke out against Trinity and questioned whether any distinction could be made between the Protestant and Catholic graduates of that college: ‘Is not the title of Catholic, assumed and used by such a Catholic medical graduate of Trinity College, Dublin, simply an added danger for the morality of our Catholic population, rich and poor?’ Soon after that article appeared, the Minister for Education, John Marcus O’Sullivan, had an interview with John Harty of Cashel. The archbishop assured the minister that the bishops were not going to make any pronouncement on the question of librarians. Cosgrave made a number of efforts to enlist the support of the bishops to kill off the embarrassing case. But the bishops did not want to have the issue formally raised at a meeting of the hierarchy. It was a matter for the local ordinary, Thomas Gilmartin of Tuam. Cosgrave met him on 25 February 1931. But the meeting did not solve much. There was a danger of the question now being broadened to include the appointment of dispensary doctors. Gilmartin urged Cosgrave to sign a concordat with the Holy See.

That was not a position with which many members of the hierarchy would have agreed. By March 1931 Cosgrave had secured strong backing within the Executive for a tough stance. He abandoned his placatory tone and confronted the more hawkish members of the hierarchy head on. A memorandum was prepared for Cardinal MacRory on 28 March:

We feel confident that Your Eminence and their Lordships and bishops appreciate the effective limits to the powers of government which exist in relation to certain matters if some of the fundamental principles on which our state is founded are not to be repudiated.

He regarded any attempt to impose a religious test on a candidate for the post of dispensary doctor as unconstitutional. Cosgrave drew attention to the delicate question of marriage dispensations on grounds of non-consummation which were granted by the church and ‘of which the civil authorities receive no notification’. He warned:

That these and other difficulties exist is not open to question. That in the present circumstances, they are capable of a solution which could be regarded as satisfying, at once, the requirements of the church and the state is, I fear, open to grave doubt. Any failure following an attempt to solve these problems would only add to the difficulty, and if it came to public knowledge, might prove a source of unrest, if not a scandal.

Seeing the gravity of the situation for future church-state relations, Cardinal MacRory had an interview in mid-April with Cosgrave. The details of the meeting are not available. But Cosgrave and O’Sullivan met Gilmartin of Tuam within days of seeing the cardinal. The western archbishop was on the defensive from the outset. He meekly suggested that Cosgrave might consider transferring Dunbar-Harrison at a suitable time. She was moved finally in January 1940 to become librarian in the Department of Defence. The outcome was, according to the Irish correspondent of Round Table, ‘fair to the lady, soothing to the Mayo bigots and good for the government’. Cosgrave ultimately lost power in a general election in 1932 in which both Cumann na nGaedheal and Fianna Fáil vied with each other to demonstrate their orthodoxy as Catholic parties.

Conclusion

The late John Whyte came to the conclusion that:

The extent of the hierarchy’s influence in Irish politics…is by no means easy to define. The theocratic-State model on the one hand, and the Church-as-just-another-interest-group model on the other, can both be ruled out as over-simplified, but it is by no means easy to present a satisfactory model intermediate between these two. The difficulty is that the hierarchy exerts influence not on a tabula rasa but on a society in which all sorts of other influences are also at work.

This qualified conclusion has not been accepted by a number of authors. Noel Browne, a former Minister for Health in the Inter-Party government between 1948 and 1951, is a strong critic of the Catholic hierarchy’s political power. An American anti-Catholic author, Paul Blanshard, described Ireland in 1954 as ‘a clerical state’. But it was not like the confessional states of Portugal and Spain:

Its [Ireland’s] political democracy is genuine, and it grants complete official freedom to opposition political parties and opposition religious groups… The church-state alliance in Ireland is unofficial and much more informal than the alliance in either Portugal or Spain. Ireland is not a police state, and it is not fascist. No Catholic bishops sit in its government councils. The Irish Republic combines the continental and medieval ecclesiastical monarchy of Rome with a modern, streamlined parliamentary system in a unique mixture, and the two organizations live in genuine amity most of the time because the state does not venture to challenge clerical authority directly and because the Church is usually discreet enough to assert its power unobtrusively.

More recently Tom Inglis has presented a view of the Roman Catholic church in Ireland as a coercive institution where ‘a rigid adherence to the teachings and practice of the Church has been the dominant type of ethical behaviour among modern Irish Catholics’.

Yet, despite the publication of a range of works in recent years — memoirs, historical monographs, sociological studies and philosophical theses — a scholar has yet to attempt to write a survey of church-state relations comparable to John Whyte’s of 1971. The archives are now available to make that possible.

Dermot Keogh is Jean Monnet Professor of European Integration Studies at University College Cork.

Further reading:

J. Whyte, Church and State in Modern Ireland 1923-1979 (Dublin 1971).

D. Keogh, The Vatican, the Bishops and Irish Politics 1919-1939 (Cambridge 1986).

J. Lee, Ireland — Politics and Society 1912-1985 (Cambridge 1989).

N. Browne, Against the Tide (Dublin 1986).