To this day Eoghan Ruadh Ó Néill remains an enigmatic figure who played his cards so close to his chest that his inner motives are still difficult to discern. Nevertheless an overall impression of what Ó Néill hoped to achieve in Ulster and Ireland in general can be gleaned from his writings and correspondence. In this his own inner struggle to provide a viable solution for the aspirations of the dispossessed Gaelic Irish and Catholic Church, while balancing the kingdom of Ireland’s constitutional relationship with Britain is of crucial importance.

Eoghan Ruadh’s personality is of major importance in to determining his actual objectives on returning to Ireland during the Confederate era. As a leader and military tactician, Eoghan was recognised as being extremely patient and imperturbable. The person who should have known Ó Néill best was his Protestant nephew Daniel O’Neill. Yet this highly respected royalist, himself renowned for his powers of perception, was unable to probe his uncle’s psyche, in the end referring to Eoghan in exasperation as ‘that subtle man’.

These character traits in conjunction with a traumatic early life in Ireland and a frustrating career in Spanish service in Flanders ensured that by the 1640s Eoghan Ruadh was a hardened soldier and a determined and patient conspirator. Furthermore Ó Néill’s fame on the continent in 1640, due to his courageous defence of the town of Arras against the French, enabled him to return to Ireland as one of the most able and respected generals of the age.

An Irish Republic

Although few things can be stated about Ó Néill’s life with any certainty, he regarded himself as a leader of the dispossessed Gaelic Irish and wished to overturn the plantation of Ulster. Over many years he took great care to establish solid contacts by marriage and promises of aid with many of the Gaelic Irish nobility of Ulster. In the run-up to the rising of 1641 he played a major conspiratorial role, sending trusted agents to Ulster who were very active on his behalf. In fact long before this, in 1627,

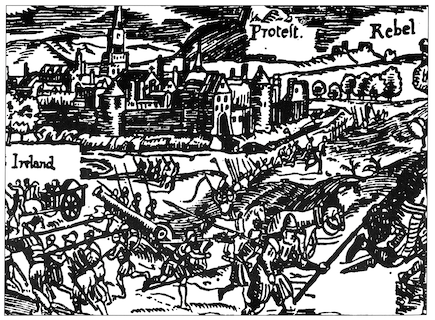

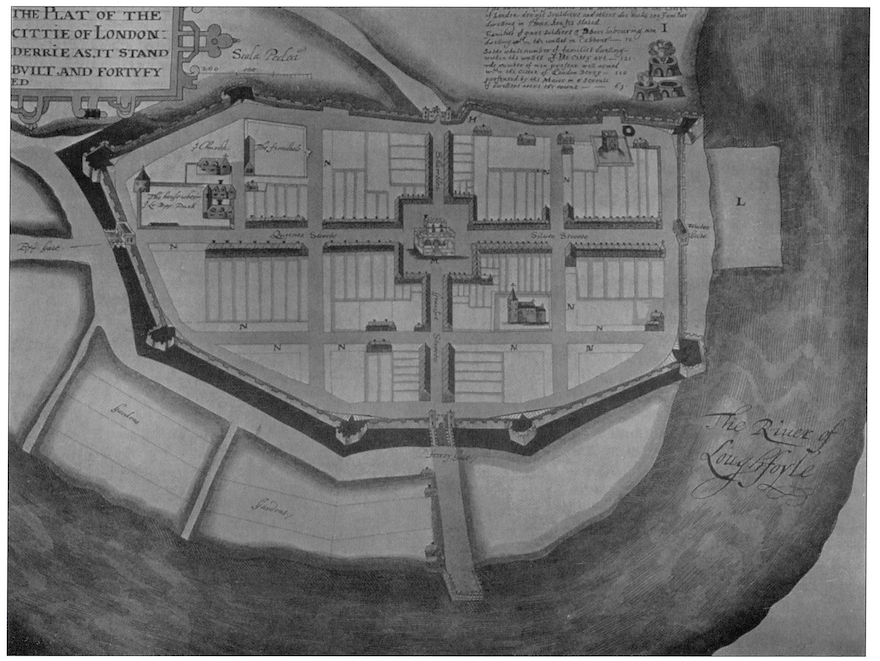

Eoghan Ruadh and his cousin Sean Ó Néill, the third Earl of Tyrone, had come close to launching an invasion of Ireland spearheaded by the Irish regiments in Flanders. In a remarkable document re-discovered by Tomás Ó Fiaich in the Brussells Archive Generales du Royaume, the two Ó Néills present to the Spanish crown a well-thought out plan not only for taking Ireland, but setting up a Catholic commonwealth to unite the Old Irish and Old English under one flag. This document in essence calls for an invasion of Ulster by the Ó Néill regiment aided by the second Earl of Tirconnell, Aodh mac Ruaidhrí Ó Domhnaill. The Irish forces were to land at Killybegs, capture Derry and set up what they called an ‘Irish republic’ by inviting the nobles and towns of Ireland to elect deputies to an Irish parliament. Then agents were to be sent to every Catholic power in Europe to solicit support for the new Irish state.

This plan never came to fruition but when Ó Néill did succeed in returning to Ireland it is clear that he intended to assume the role of a conciliatory force amongst the Catholics of Ireland. Father Hugh Burke, one of Eoghan Ruadh’s Franciscan agents on the continent stated that Ó Néill ‘goes not there to command, but to receive what they may be minded to accord him and lay upon him…as he claims only the right to serve God and enjoy the portion that falls to him of his father’s inheritance’.

Enemies

However on being elected General of Ulster, Ó Néill made a number of influential enemies in Ireland. Sir Feilim Ó Néill, who had pretensions to become Earl of Tyrone, resented being demoted as leader of the Ulster Irish and was not content with the post of President of Ulster. It is also clear that the Old English never really trusted Eoghan Ruadh, a fact that he complained of in a letter to Ormond in 1646, when referring to ‘the many undeserved enemies I have in this kingdom’. At an early stage Ó Néill attempted to establish an element of trust between himself and the Supreme Council at Kilkenny by bestowing his two frigates on the Confederate navy. However the author of The aphorismical discovery, admittedly a very pro-Ó Néill source, states that ‘I have never heard that he ever got by it as much as thanks’. While the Old English distrust of Eoghan Ruadh may have stemmed from residual memories of Ó Néill raids and the Nine Years War, the major factor was their fear of the radical changes in the 1641 status quo demanded by many in the faction which Ó Néill commanded.

Eoghan Ruadh soon became allied to the most determined churchmen such as Eber Mac Mathghamna, the bishop of Clogher and an tAth. Baothgalach Mac Aodhagain. These Counter Reformation clerics often sought a return of traditional church property which may not have bothered the Gaelic Irish of Ulster but certainly created unease amongst the Old English, many of whose estates such as those of Richard Bellings, the secretary to the Confederacy for much of this period, were made up largely of ancient church lands. The Old English also had no desire to come under Spanish influence, a link which they saw personified in Ó Néill. These perceived threats persisted to cloud Ó Néill’s relationship with the supreme council at Kilkenny. In the end they ensured that he was never able to rise above being an Old Irish leader. As a result Ó Néill was forced to rely for support on the alienated Gaelic and Gaelicised families of Connacht, Leinster and Munster, who although often very eager adherents, never had the resources to greatly contribute to his forces.

The nuncio’s party

Indeed as factions began to emerge within the Confederacy, Ó Néill came to gravitate more and more towards the extreme Catholic faction. Links with the papal nuncio, Cardinal Rinuccini, were very important as they gave Ó Néill his first adequate supplies of military equipment which allowed him to inflict a crushing defeat on the Scots at Benburb on 5 June 1646. Ó Néill and the nuncio decided to prevent any peace being made between the Catholic Confederates and the Marquis of Ormond, by using the prestige of the victory of Benburb to topple the Ormondists on the Supreme Council. In a letter dated August 1646, Ó Néill gives a very good indication of his agenda at the time when he wrote to the nuncio that ‘I am of the opinion that in order to prevent the pernicious cancer from eating into the sound members of our body, steps should energetically be taken against the treachery of this cowardly peace by fulminating ecclesiastical censures against its authors and abettors’.

Coup d’état

This was why Ó Néill marched south in August 1646, leading many later commentators to accuse him of not following up his victory in Ulster, something which was beyond his army in any case without siege equipment, heavy artillery or the ability to blockade the North Channel. In fact if Ó Néill had not marched south he would have alienated his clerical supporters who were his only allies. In the short term Ó Néill’s march south was quite successful as it induced Preston and the Leinster army to join with the nuncio and himself in staging a coup d’état and shoring up the Confederacy.

Despite the success of the 1646 coup d’état, the Old English soon regained their dominant position on the Supreme Council because of their control of the organs of the Confederate administration. Also a number of incidents served to weaken Ó Néill’s credit at Kilkenny. His seizure of the important strategic town of Athlone caused mistrust between the General of Ulster and the Supreme Council. In 1647 a further controversy arose in Ireland due to the arrival of Conchobhair Ó Mathghamhana’s book Disputatio apologetica de iure regni hiberniae published in Portugal in 1645, which called on the Irish Catholics to establish their independence by expelling the colonists and electing a leader of their own. The Ormondists felt that this was a ploy to make Ó Néill king of Ireland. Later a third controversy broke out in 1648 when Luke Wadding sent the sword of Aodh Mór Ó Néill to Eoghan Ruadh. This gift which had associations with papal approval of an Ó Néill monarchy caused uproar in Old English circles. As a result, in 1647, the Ulster army was sent to Connacht to keep it out of the way. Not surprisingly the army mutinied when called back to defend Leinster after Preston’s disastrous defeat at Dungan’s Hill. The mutiny was sparked off by pay but the real underlying issue was, as some of the Ulster officers put it, their being ‘absolute slaves to the Supreme Council, which contributed nothing to their maintenance’.

The peaceful quelling of the mutiny gave Ó Néill another opportunity to reiterate his position as regards the Confederate Catholics. On this occasion he told his assembled troops that ‘I told you often, and the generality of the nation, that I came to this kingdom with intent to serve the king and the nation in general, and in particular the province wherein I was born…and do believe nothing will more endear or create a better understanding between you and the rest of your countrymen than a timely relief of this kind in time of need’. It can be seen by this speech that Ó Néill regarded the Old English as his fellow countrymen and saw 1647 as a perfect opportunity to effect a reconciliation with the southern provinces. In the end the Old English continued to regard Ó Néill with suspicion, although Ó Néill did succeed in garnering much support amongst the Gaelic and Gaelicised families of south Leinster, Clare, Tipperary and Kerry due to his protection of these areas.

The split

Indeed in 1648, when the confederate Catholics finally split over the issue of a truce with Inchiquin, Ó Néill was very reluctant to fight his fellow countrymen even when they attacked him. When opposed by Irish Catholics he issued orders to Colonel Laeighseach Ó Mordha not to kill any of his opponents ‘but in proper defence’. On one occasion Ó Néill even went so far as to deliberately capture thirty of Preston’s troopers and then enjoyed himself by showing ‘himself loving, more like a dear father to his children than any way an enemy and preached them the error of their ways’.

In June 1648, Ó Néill and his Ulstermen issued a declaration against the cessation in which they made it very clear that they regarded themselves as remaining loyal to the Catholic confederacy and also that they put great store by the oath of association, which they regarded as being broken by the Ormondists:

We have by free and full consent without any reluctancy, in the view of the world, taken the oath of association appointed by universal votes to be taken by all the Confederate Catholics of Ireland, wherein we manifest our religion towards God and secure our loyalties towards our sovereign. This oath we have as frequently and as freely iterated as any of the rest of our fellow Confederates of this Kingdom… We provoke the whole world to charge us with the least act of disloyalty.

It is evident that Ó Néill and his Ulstermen believed that it was they who were upholding the Confederacy. For them it was synonymous with loyalty to the nuncio. It is also clear that the oath of association meant a great deal to these men and that it was their opponents whom they regarded as being disloyal. Indeed in this instance it was the more staunchly Gaelic element in the confederacy which attempted to preserve it, which paints a very different picture than that given by many Old English observers.

Truce with parliament

For 1649 two documents enable us to get closest to the aims of Ó Néill and his party. In April 1649, Eoghan Ruadh signed a three month cessation with the parliamentarians in Ulster under George Monck to take effect on 1 May. In return for relieving Derry, Ó Néill received powder and ammunition from Sir Charles Coote. These actions were taken to keep the Ulster army supplied. In addition Ó Néill set out terms for joining the Parliamentarians in an effort to get a just settlement for his people, terms which would have ensured the reversion of Ulster to its pre-1603 position.

In the Draft of the Propositions of General Owen O’Neile, the Lords, Gentry, and Commons of the Confederate Catholics of Ulster, to the most potent Parliament of England Ó Néill not only asked that all discriminatory laws passed against Catholics since the twentieth year of Henry VIII be rescinded, and this to extend to his people and their successors for ever, but also that an ‘act of oblivion’ be passed for all things done by his party since 1641, and that all lands taken from them since 1603 be restored and that Ó Néill be put back in possession of his father’s estates. He also demanded a place in the army ‘befitting his worth, place and quality’ and that his men ‘be eligible for all posts of trust, civil and martial, by sea and land’ and that they should be given a seaport and provisions for an entire army. Although Ó Néill must have known that the negotiations would end in failure, as they eventually did, Monck did his best submitting a rearranged draft to Ó Néill entitled Propositions that Colonel Monck thinks the Parliament will consent unto which in themselves were quite favourable to the Ulster Irish.

Alliance with Ormond

When the truce with the Ulster parliamentarians eventually broke down, Ó Néill came to terms with the Marquis of Ormond after the outstanding issue of his opponents’ excommunication was dealt with to his satisfaction. The articles signed on 20 October 1649 contain much more realistic terms and represent the bottom line of Ó Néill’s demands for himself and his loyal followers. This note of realism was reinforced by Ó Néill’s inclusion of a clause which stated that the nobility and gentry of Ulster alone had the right to choose his successor in the event of his death. The terms agreed with Ormond made provision for an Ulster army of 6,000 foot and 800 horse, with Ó Néill’s only superior being Ormond himself. Ó Néill’s adherents were also to have the benefit of an act of oblivion. These concessions in themselves were substantial, holding out the prospect of a just settlement in Ulster in the event of a royalist victory. Ó Néill had tried to do his best for his people, but he died on 6 November 1649 and his followers never enjoyed the benefit of these articles.

Conclusion

The writings of Eoghan Ruadh Ó Néill and the various documents which concern him all tend to point to his conciliatory role, not only in Ulster, but in the country in general. He accepted the framework provided by the Catholic Confederacy and did not break the oath of association until October 1649 when the Confederation was defunct to all intents and purposes anyway. Ó Néill regarded himself as leader of the dispossessed Gaelic Irish but any disagreements which arose with the Old English as a result were generated by genuine differences of opinion as to what policies the Catholic Confederates should pursue. Old English historiography has been very successful in depicting the Gaelic Irish as ambitious intriguers. As Massari, the nuncio’s secretary, at one stage pointed out, the Old English continually attempted ‘to create the impression that the good Catholics of Ulster were all ferocious barbarians, untrustworthy and untamed’.

If the surviving evidence is taken into account Ó Néill’s Ulstermen and his other adherents in Connacht, Leinster and Munster seem to have been more faithful to the oath of association than many of their erstwhile Old English compatriots. According to this view Ó Néill’s faction played a major centre-stage role in Confederate Ireland, saving it in 1646 and again in 1647, until the weight of Ormondist opposition eventually became too great, helped in large measure by the fragmentation of the

Ulster army itself into Ormondist and nuncioist factions in the spring of 1648. That Ó Néill then managed to keep his army together, although surrounded, seriously weakened and with almost no ammunition must stand as one of his greatest achievements. Much of the Old English distrust of Eoghan Ruadh Ó Néill was unjustified (although if the Ormondist clique had always intended to destabilise the Confederation from within, then they had good reason to be wary of him) and he was more committed to the ideal of the Catholic Confederation than many later writers have been willing to acknowledge.

Darren Mac Eiteagain is a postgraduate research student at University College Dublin.

Further reading:

J.I. Casway, Owen Roe O’Neill and the struggle for Catholic Ireland (Philadelphia 1984)

Gillespie, ‘Owen Roe O’Neill c.1582-1649: soldier and politician’, in Nine Ulster Lives (Belfast 1992).

T. Ó Fiaich, ‘Republicanism and separatism in the seventeenth century’, in Leachtaí Cholm Cille 2, (Ma Nuad 1971).