The growing popularity of the Parnell Summer School at Avondale derives from the interesting balance its programmes have struck between sessions on Charles Stewart Parnell and his times with those focusing on current events and newer historiographical approaches. One of the best attended sessions this year provided new insights and analyses on the role of women in nineteenth and twentieth century Irish political, economic and social history.

Maria Luddy (Wawrick) traced how the active public roles played by Irish women in the communal and popular politics associated with Repeal agitation, tithe protests, food riots and parliamentary elections gradually diminished in the post Famine era under the combined influence of steadily declining employment opportunities for rural women, the Catholic devotional revolution and the mid-Victorian emphasis on domesticity. The first signs of an emerging feminist political consciousness associated with protests against the Contagious Diseases Acts and the land agitation in the 1870s were eclipsed by the constitutional struggle over the Union beginning in the mid-1880s. For the next forty years, most Irish women put greater priority on their nationalist or unionist identity than on common gender concerns, thereby inhibiting further growth of a feminist movement until recent decades.

Dympna McLaughlin (Maynooth) documented the ways increasingly rigid definitions of female respectability both marginalised and oppressed working class and poor women after 1850. Previously used strategies for economic survival such as begging, working as migrant agricultural labourers or in urban factories were now seen as totally incompatible with women’s ideal roles as wives and mothers and as guardians of society’s moral stability. The growing disdain for those who did not conform to this bourgeois domestic ideal was reflected in rising rates of female occupancy in workhouses, the detention of prostitutes and those with venereal diseases in hospitals, and growing female dependence on religious charitable institutions. The definition of offensive female behaviour broadened to such an extent that by 1891 women could be incarcerated for Charles Stewart Parnell using abusive language in public. A keen awareness of the social ostracism and economic hardship attached to single motherhood rather than naive innocence or prudishness seems to have kept the rates of pre-marital sex for young Irish women relatively low. Emigration, abandonment or infanticide were frequently the only options available for single women who became pregnant. In fact, it was the sacrifices of poor and working class women which made it possible for their more fortunate sisters to aspire to the idealised status.

In the concluding paper Margaret MacCurtain (UCD) described the way changing patterns of land usage and inheritance affected Irish rural women. Despite the dramatic population decline of mid-century, the complex interaction of a continuing perception of land scarcity, persistently high rates of marital fertility, farm consolidation and widespread conversion from tillage to pasture significantly narrowed the personal and career options for women. The need for a sizeable marriage dowry of land or cash meant that most farm families could provide for only one daughter and usually her husband was considerably older. Her female siblings were expected to emigrate at an early age to the urban centres of Britain or America to earn as domestic servants or factory hands their own livelihood and remittances for the family back home. The tradition of patrilinear land succession, the continuing exodus of rural women across the sea or into increasingly cloistered religious orders, and the fraternal bonding that tool place at GAA events and in the expanding number of public houses laid the foundations for the male dominated social and cultural values which characterised the Irish countryside until recent decades. She concluded that the well-intentioned yet restrictive provisions relating to women and marriage that Eamon de Valera wrote into his 1937 constitution gave de jure recognition to patterns and attitudes that had been deeply embedded in Irish society as early as 1900. Thus this document reflected broadly accepted societal values and was not solely the product of de Valera’s personal attitudes and experience. All three presentations bore testimony to the resilience, courage and initiative of Irish women in meeting the challenges that major economic and social transformation presented in the post-Famine era.

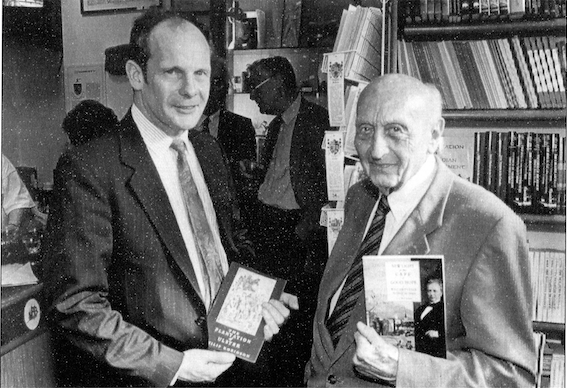

Philip Robinson (left), author of The Plantation of Ulster, and J.L. McCracken, author of New Light at the Cape of Good Hope at the Ulster Historical Foundation’s recent book launch.