KIERAN KEENAGHAN and JAMES SCULLY

Offaly History

€20

ISBN 9781909822429

Reviewed by

Eileen Casey

Eileen Casey is a poet, fiction writer and journalist.

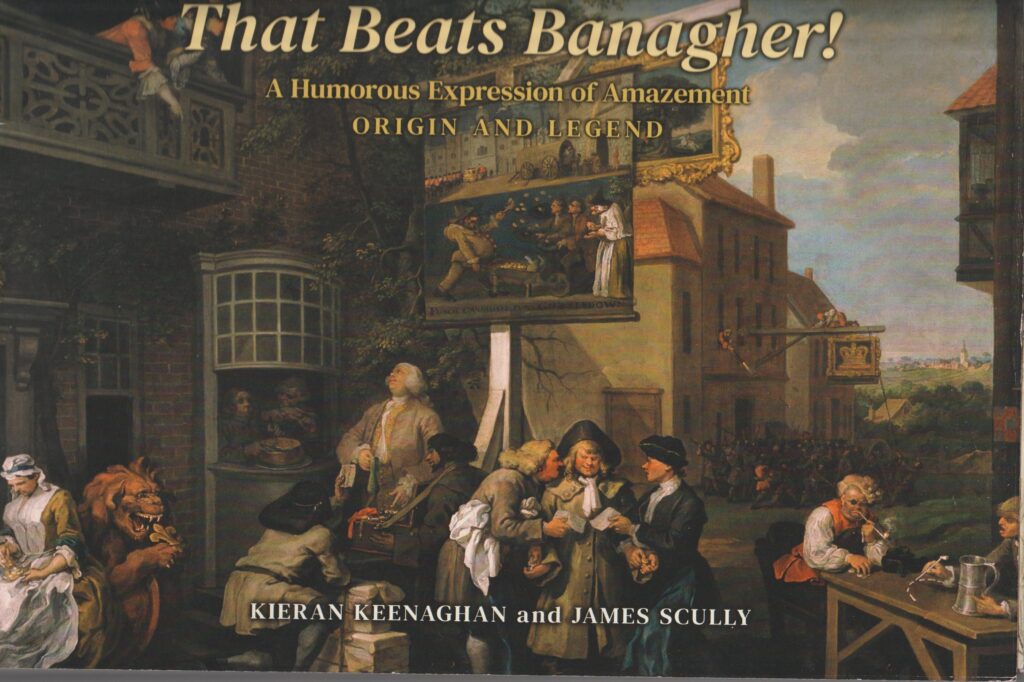

Co-authored by local historians Kieran Keenaghan and James Scully (recipient of a Heritage Hero Award), this handsome full-colour edition addresses any lingering doubts or questions about an expression in spoken usage for well over 200 years. Original source material, sumptuous images, maps and illustrations provide historical depth, interesting anecdotes and illuminating characterisations.

For example, consider Banagher’s globally recognised association with the great novelist Charlotte Brontë. Banagher, Co. Offaly, is where her husband, Arthur Bell Nicholls, lived out his later years. When he died in December 1906, the Westmeath Gazette, announcing his passing, included a brief history of the expression. It claimed that political corruption lay at its root, a claim supported by Keenaghan and Scully through well-researched documentation. The authors clarify, however, that, although linked with Machiavellian machinations in the political arena, the phrase was, bizarrely, used ‘in a positive manner’. In fact, they make the assertion that common usage frequently connotes not derision so much as admiration or amazement—‘getting one over’, in popular parlance.

By the time Charlotte Brontë visited Banagher in 1857 the phrase was well established, appearing worldwide in newspapers, books and scripts, for example in the Bombay Gazette in July 1823. Also included is the very first reference to the phrase in the Dublin Evening Post in September 1821. The authors have been diligent in finding print outlets that refer both to Banaghan and Banagher. The Edinburgh Gazette in 1822 opts for Banaghan, describing it as ‘a town of Ireland, in King’s county, situated on the river Shannon, which, before the union, sent two members to the Irish Parliament’. Something similar appears in the London Gazette in 1823 and in the Nouveau dictionnaire geographique. This variation was already in use as early as 1787, as recorded by Francis Grose in his popular A classical dictionary of the vulgar tongue. Grose’s dictionary brimmed with colourful turns of phrase, attributing this particular Irishism ‘to someone who tells extraordinary or exaggerated stories’. ‘That beats Banaghan’, found in the 1834 novel Rockwood by William Ainsworth, featuring highwayman Dick Turpin, is just one of hundreds of examples.

Included is mention of Daniel O’Connell’s repeated use of the phrase during his speeches in support of Repeal in the 1830s and ’40s, which ensured its growing popularity at that time (although O’Connell sometimes used the original Banaghan instead of Banagher). ‘Bates’ or ‘bangs’ was often interchangeable with ‘beats’. ‘Banagher beats the devil’ was a later variation.

The phrase, as the Westmeath Gazette rightly concluded, indeed has its origin in the scandalous swapping, buying or selling of the borough of Banagher, a borough first established in 1629. Before the Act of Union in 1800, Banagher elected two members of the Irish parliament. As with all lofty positions, being an MP was much sought after. Powerful, wealthy individuals controlled the ‘election’ process. In 1787 James Alexander, who purchased Banagher borough from the incumbent Peter Holmes, swapped it for the borough of Newtownards, thus ushering in the Ponsonby era in Banagher. As time went by, these people were considered to have the ownership of a borough or borough control so that it could be bought, sold or even bequeathed. Banagher borough was notorious for these practices. Democratic process simply didn’t exist. Sold and swapped in 1787, it was this trait that set it apart from other boroughs and gave rise to the astonished tone of ‘That beats Banagher!’

Humour is also found within these pages. Anecdotal relief appears with purpose, revealing how the phrase is not just confined to Banagher or Ireland but has a global reach. In October 1891, the Birmingham Express reported on a ‘Yankee paper’, detailing how a lady in Missouri divorced her husband for incompatibility. She subsequently fell in love with him again and they remarried. This occurrence is reported as ‘beating Banagher’. The lady is warned, however, that she cannot again enter a plea of incompatibility because her husband and herself are two fools together or folie à deux, as the French saying goes.

A strength of this publication is the balance between historical fact, anecdotal humour and tragic consequence. The swapping of Banagher with Newtownards in 1787 is one example. A few short years before, Peter Holmes and Edward Bellingham Swan were the Banagher MPs. Swan had paid £1,400 for his Lanesborough seat in 1771, and when he replaced the existing MP in Banagher in 1785 he would have paid Peter Holmes a considerable sum. Such wheeling and dealing put him under enormous stress, so much so that he took his own life.

Bribes, compensation and massive inducements were never more prevalent than when voting for or against the Act of Union, the aftermath of which reduced Ireland to a backwater. The equivalent of one billion pounds in today’s terms was spent. William Brabazon Ponsonby received a bribe of £15,000 as compensation for the loss of Banagher borough. Now that, indeed, beats Banagher!

I thoroughly recommend this publication, mostly for its depiction of time, place and character. Overall, it’s an enjoyable, thought-provoking read.