By Christine Kinealy

Many Irish people are aware that in Black ’47, possibly the deadliest year of the Great Hunger, members of the Choctaw Nation in Oklahoma raised $170 to help the starving poor in Ireland. This act of generosity from people who themselves had been colonised, impoverished and displaced is the best-known example of Famine philanthropy. Over the last four decades, the Choctaw gift has been commemorated in multiple ways—in public ceremonies, artwork, music, scholarships, donations to Native Americans during the Covid-19 pandemic, and in both scholarly and children’s books. In addition to understanding the historical context of this gift, recent research has broadened our appreciation of the cultural context. The Choctaw people themselves use the concept of ima, which translates as ‘to give’, to help explain the generosity of their ancestors to people with whom they had no direct connection.

Given the deep and ongoing interest in the Choctaw donation, it is surprising that little attention has been paid to the contributions of the Cherokee Nation. Yet their involvement is no less impressive and is part of a larger story regarding the remarkable contributions of indigenous peoples, in both the US and Canada, to Ireland in 1847.

FORT GIBSON

On 13 March 1847—ten days before the Choctaw Nation met in Skullyville—a meeting was held in Fort Gibson, a garrison located on what was referred to as the ‘Indian Frontier’ but later became north-eastern Oklahoma. The purpose of the meeting was to talk about the Famine in Ireland. It was convened by Lt. Gen. Gustavus Loomis, the commanding officer at the garrison. Loomis, a veteran of the war of 1812, served in this position twice. During his first tenure (1843–4) he had built a school and church at the fort. His second and final command (1846–8) was more controversial, with complaints made to the War Office that he was ‘teaching negroes in a slave state to read—and possibly to write’.

Inside the fort’s chapel, soldiers, traders, agents and Cherokees were read first-hand accounts of the suffering of the Irish poor. Over $100 was raised, which was sent to Mayor Andrew Mickle in New York, a member of the General Relief Committee for Ireland that had recently been formed in the city. On 10 May 1847, the committee recorded that $103.30 had been received from ‘Hon. A.H. Mickle’, which consisted of ‘donations from Fort Gibson in the Cherokee nation, by Richard H. Coolidge, Assistant Surgeon, through Edward Coolidge’.

The founder and president of the General Relief Committee of New York was a man who had no connection with Ireland. Myndert van Schaick was a successful businessman who belonged to one of the city’s oldest Dutch families. He stated his reasons for getting involved: ‘I might be able to accomplish some good to a greatly abused and suffering people’, and ‘we hope our operations will save some lives, heal some broken hearts’. Van Schaick was assisted by an Irish-born Quaker, Jacob Harvey. They worked closely with the Quaker Committee in Dublin, thus ensuring a fast and fair distribution of the money and food sent to Ireland. When the General Relief Committee closed their operations in early 1848, they had raised $171,374 in cash and provided provisions to the value of $242,042.

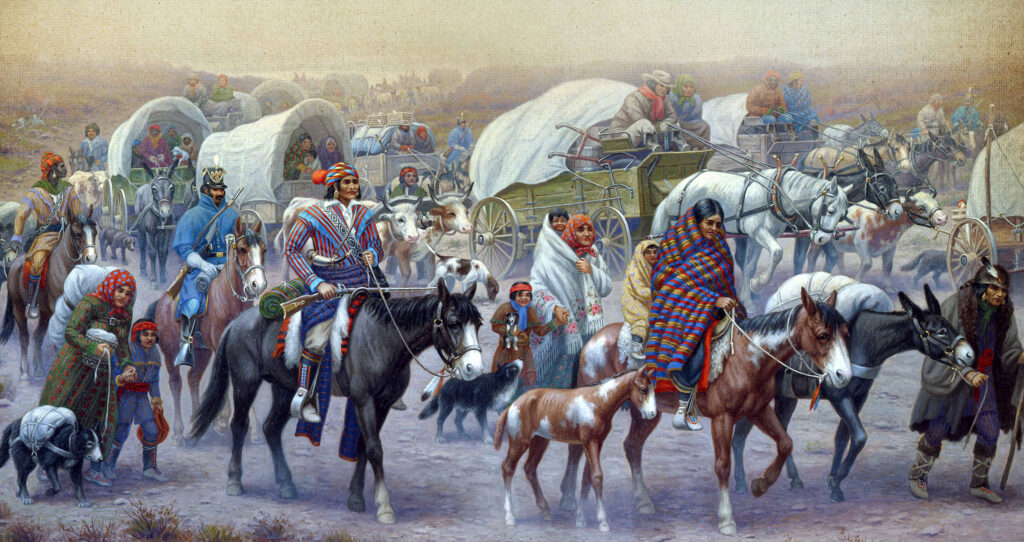

TRAIL OF TEARS

The timing of the Cherokee donation to the General Relief Committee was especially impressive given their recent history. Like the Choctaws, the Cherokees were one of the Five Tribes that had been forcibly moved from their ancestral homes during the Trail of Tears. In 1830, President Andrew Jackson (the only US president whose parents were born in Ireland) had signed the Indian Removal Act, authorising him to take land east of the Mississippi River—the ancestral homelands of the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole Nations—in exchange for land in the west, to be named Indian Territory. In total, Jackson signed nearly 70 treaties, forcing the relocation of around 70,000 Native Americans.

Overseen by federal troops, the displaced people were compelled to march up to 1,200 miles along various routes, known as the ‘Trail of Tears’. Shortages of wagons, horses and food, together with harsh weather, added to their difficulties. An estimated one in four people died, with every family losing at least one member. The wife of Coowescoowe, also known as Chief John Ross of the Cherokees, died on the Trail. The Cherokees had been one of the last groups to be removed, their displacement commencing in late 1838, meaning that it was still a recent memory at the time of the Famine. Moreover, in 1847 they were still adjusting to living in a hostile environment that included white settler aggression.

CHEROKEE NATION NEWSPAPER

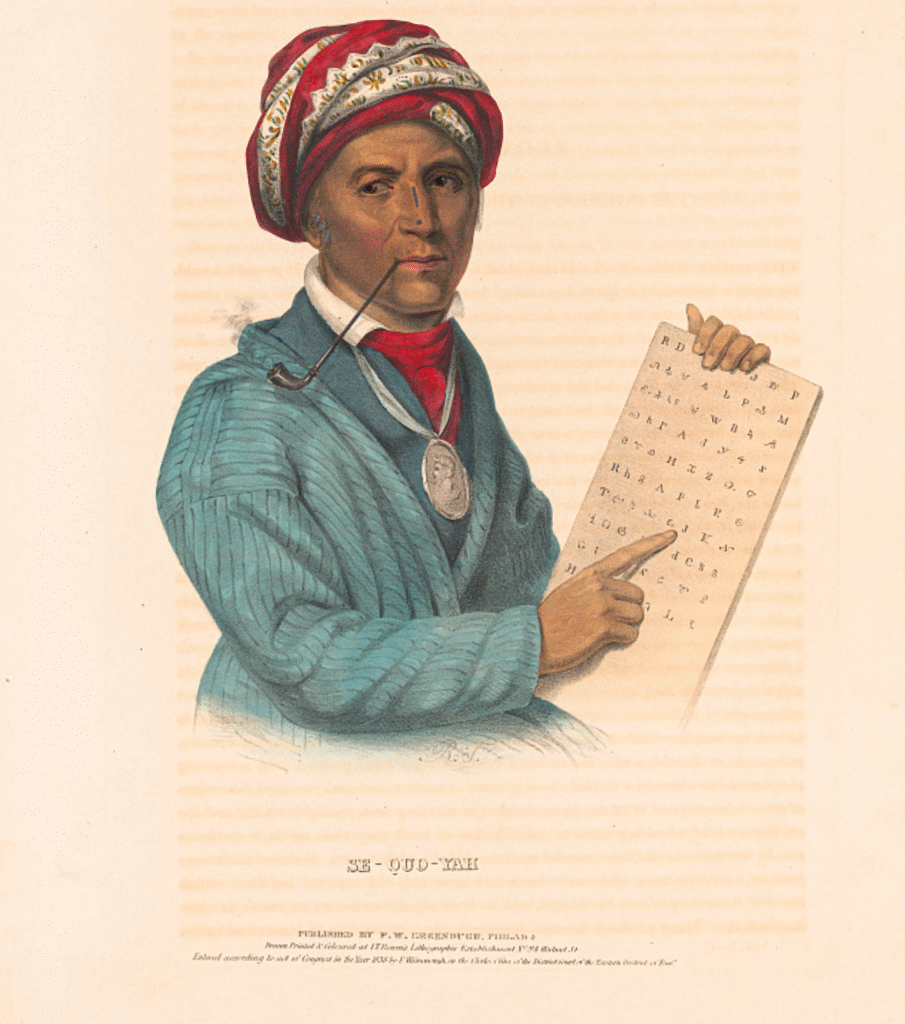

News of the failure of the potato crop in Ireland and in the Highlands of Scotland was widely reported in American newspapers. In Indian Territory, there was an active white and indigenous press. The former included the Arkansas Intelligencer, which was allied to the Democratic Party and was both pro-Irish and pro-slavery. In 1844 the Cherokee Advocate had been founded. It was bilingual, providing news in both English and in Native Cherokee syllabaries. The latter had been created by Se-Quo-Yah, who had been born around 1775 to a Cherokee mother. He believed that white supremacy existed because white Americans possessed a written language that allowed them to accumulate knowledge rather than being dependent on memory. In the 1820s he developed a system of symbols representing the syllables of the Cherokee language. This facilitated the transmission of news to both Native and English speakers. Consequently, the Cherokee Nation played a pivotal role in informing the Cherokee people of the Famine in Ireland and Scotland.

The meeting in Fort Gibson did not mark an end to Cherokee involvement in Famine relief, as money continued to be raised for Ireland in the following weeks, the final donation climbing to $130. John Ross, the principal chief of the Cherokees, whose own ancestors were Scottish, was worried that the focus on Irish distress was to the detriment of the situation in Scotland. On 28 April he wrote to the editor of the Cherokee Advocate on behalf of the poor in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Because of intermarriage between the two groups, he believed that Scottish people had a ‘special claim’ on the Cherokees. Ross suggested that a meeting be held on 5 May at Tahlequah for this purpose. At the meeting, $171.24 was raised for Scotland and forwarded to the Scottish Relief Committee in Philadelphia. A second donation of $55.25 was sent a few weeks later.

GADUGI

The Cherokee Advocate continued to report sympathetically on the deteriorating situation in Ireland and Scotland. On 13 May it published an article entitled ‘The Famine Lands’. Referring to the money already donated by the Choctaws and the Cherokees, it called on all tribes in the Nation to contribute, even if they did not have much to spare. The article acknowledged that they were separated from the sufferers by thousands of miles, but reasoned that ‘It should be enough for us to know that those who are dying for bread are our fellow beings and probably from the same families from which some in the nation have descended’. The appeal added: ‘Though we may never receive pecuniary benefit, or aid in return, we will be richly repaid by the same consciousness of having done a good act’. Just as the concept of ima was embedded in Choctaw culture, Cherokees had a similar concept of gadugi, a belief in community and mutual support, and giving to strangers because it was the right thing to do, not for transactional reasons.

Articles on Ireland that appeared in the Cherokee Advocate served a further purpose. The newspaper had become an important tool in the struggle to maintain tribal sovereignty. In this context, journalism became a way of maintaining Cherokee unity and asserting their right to be independent. Moreover, decades of broken treaties, betrayal, land colonisation, and forced cultural and religious assimilation meant that their encounters with colonialism had parallels with the Irish experience. Reprinting articles that blamed the Famine on ‘the unfortunate misgovernment of the country’ and reports on the chaotic and deadly mass exodus of Irish people from their ancestral home would have resonated with Native readers. Graphic accounts of deaths from hunger and disease, and of people being buried without traditional funeral rites or simply left at the roadside by their enfeebled relatives, would inevitably have reawakened memories in the readers of their own losses during the Trail of Tears. Sympathising with the Irish, whom the paper referred to as ‘warm-hearted’ people, therefore took on a further meaning. It provided a way not only of criticising the British government but also of critiquing all governments who abused their power over colonised peoples.

PROOF OF THE SUCCESS OF THE ‘CIVILIZING MISSION’?

The Cherokee donations to Ireland were noted in the American press, but they were viewed through a white, Christian and racialised prism. Rather than seeing these acts of generosity as examples of Indigenous humanity, they were interpreted as proof of the success of the ‘civilizing mission’ undertaken by the government and the churches. The US Gazette averred:

‘Among the noble deeds of disinterested benevolence which the present famine has called forth, none can be more gratifying to enlightened men that the liberality of our red brethren in the Far West … Christianity has taught them that “God hath made of one blood all nations of men to dwell upon the face of the earth”.’

The Philadelphia Committee informed Chief Ross that the donations to Scotland were evidence of ‘your people having attained to a higher and purer species of civilization derived from the influence of our holy religion’.

Donations to Ireland had come from all parts of the world in early 1847, but most of them dried up by the end of the year, partly in response to the British government’s assertion that the Famine was ‘over’. It wasn’t; evictions, emigration, disease and deaths continued to rise in the years that followed. For a brief period, though, a spontaneous and unprecedented fund-raising movement on behalf of the Irish poor had resulted in many acts of philanthropy. Within this global crusade of giving, the gifts from the Cherokee and Choctaw Nations remain inspiring, especially when viewed in the context of their own recent histories and their ongoing struggles for survival and autonomy. The Cherokee donations to Ireland and Scotland can be interpreted as acts of both resistance and agency in asserting empathy and sympathy with other subjugated people. At the same time, the willingness of the Cherokees to come to the aid of ‘our fellow beings’ suggested the continuation of a set of values that had survived colonial oppression and acculturation. In this case, gadugi transcended racial, religious, cultural, geographic and familial boundaries, and it deserves to be remembered.

Professor Christine Kinealy is Director of Ireland’s Great Hunger Institute at Quinnipiac University.

Further reading

C. Kinealy, Charity and the Great Hunger in Ireland: the kindness of strangers (London, 2014).

J. King, M.G. McGowan & A. Shrout, in C. Kinealy & G. Moran (eds), Forgotten heroes of Ireland’s Great Hunger (Cork, 2024).

L. Howe & P. Kirwan (eds), Famine pots: the Choctaw–Irish gift exchange, 1847–present (East Lansing, Mich., 2020).