By Fintan Lane

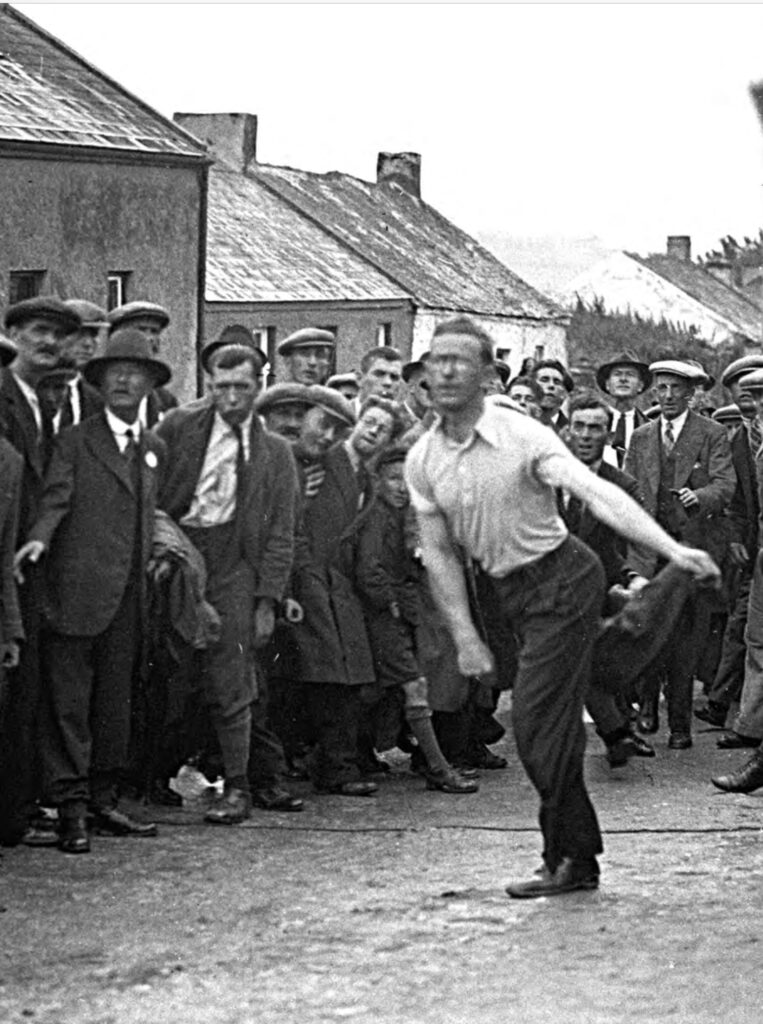

Road bowling—an elemental and deeply rooted sporting tradition in Ireland—has fascinated many with its blend of skill, physical endurance and local pride. It is a curious game that can feel like an archaic leftover from wildly different times, before roads were made perilous by heavy traffic. Played by pitching a 28oz. iron bowl along back country roads with the objective of covering a set distance in fewer throws than one’s opponent, road bowling is both a cultural practice and a competitive sport. Like horse-racing, it has been traditionally associated with significant gambling and played for ‘stakes’. Now largely associated with counties Cork and Armagh, its history is far richer than is often acknowledged.

The provenance of road bowling—called ‘bullets’ in Armagh—remains an issue of debate among enthusiasts. Some argue that it is an ancient Irish sport, others suggest that it came over with Dutch soldiers in 1689, while another theory is that it was introduced by English and Scottish migrants. Road bowling was certainly played in Ireland by the beginning of the eighteenth century. Unlike the traditional Gaelic game of hurling, however, there is no clear evidence to suggest that it has ancient roots in this country. By far the most plausible explanation is that the sport was introduced into Ireland by British textile workers, particularly weavers. The English traveller Edward Wakefield observed in 1812 that it was ‘much practised by the weavers’ in Ulster, especially on flat rural roads. It was clearly a lower-class sport, requiring little equipment—just a metal or stone bowl and a playing surface.

‘LANG BOWLIS’

To fully understand the origins of road bowling, we must look to Scotland and northern England, where similar games have been played for centuries. In Scotland, ‘lang bowlis’ was mentioned in 1496 in the Scottish lord treasurer’s accounts. By the mid-1600s, long bullets had become widespread throughout lowland Scotland, especially in weaving communities. Initially enjoyed by both gentry and commoners, bulleting gradually became associated exclusively with workers by the mid-eighteenth century. A variety of formats existed in Scotland—some involved using leather slings to propel the bowl—and the game was played on open commons as well as on roads. By the early 1800s, however, the sport was in decline owing to increased road traffic and official restrictions. It became a cultural casualty of the industrial revolution.

In England, road bowling was once common in west Yorkshire and east Lancashire, and among the mining communities of south Northumberland. As in Scotland, it was primarily a weavers’ and miners’ pastime, but by the late nineteenth century had largely disappeared, driven out by traffic concerns and élite disapproval. Long bullets also crossed the Atlantic. By the 1720s it was widely played in the American colonies, primarily by Scottish and Scots-Irish settlers, and was often accompanied by heavy gambling. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, it had disappeared from the American sporting landscape. In recent decades it has made a minor comeback in the United States, promoted by admirers of the Irish game.

LONG BULLETS IN ULSTER

Ulster was pivotal in the emergence of Irish road bowling. In the early eighteenth century, as weaving and spinning became more developed in the north, Scottish and English artisans migrated to Ulster to work in the burgeoning linen industry. These workers almost certainly brought the game of long bullets with them. It is possible that it existed in Ireland to some extent from the late seventeenth century.

In 1714, a city ordinance in Derry banned the game from the city’s ramparts, imposing a five-shilling fine on offenders. The sport was also present in Antrim and Armagh. Further south, according to historian James Kelly, long bullets was listed as an objectionable recreation in Dublin city in 1737. Jonathan Swift mentioned the game in a satirical poem in 1729, written during a visit to County Armagh. He poked fun at the unkempt Tady, a bullet player, whose lice-ridden head was tended to by a smitten Sheelah:

‘When you saw Tady at long-bullets play,

You sat and loused him all the sunshine day …’

Bullets was popular among Ulster’s weavers, most of whom were Presbyterians or Anglicans. Over time, however, the game also found players in the Catholic community, especially in mixed urban areas such as Belfast and around Armagh city.

INDUSTRIALISATION AND DECLINE

The sport began to decline in Ulster during the nineteenth century. With the rise in road traffic and the introduction of laws prohibiting games on public highways—notably the Summary Jurisdiction Act of 1851—the authorities cracked down on road bowling. Simultaneously, the march of technology and industrialisation changed how people lived, worked and played. For example, weaving, once a domestic occupation, became more concentrated in factories. Handloom weaving remained resilient as late as the 1870s, but the impact of mechanisation was increasingly felt. A broader cultural shift emphasised ‘respectability’ and industriousness. Activities such as cock-fighting and road bowling were increasingly seen as dangerous and unsuited to the disciplined moral order of modern industrial society.

The Ordnance Survey Memoirs of the 1830s offer glimpses into this societal transformation. Surveyors noted a reduction in public pastimes and linked this decline to ‘improved habits of industry and frugality’. While road bowling was still noted in Antrim and parts of Derry during this time, it had disappeared in other places where it had once thrived. The sport survived in Armagh and east Tyrone, where by the late 1800s it was largely associated with the Catholic community. It also remained remarkably widespread for much of the nineteenth century around Belfast, according to John Gray, partly because of ‘massive immigration from rural handloom weaving areas where bullet throwing had been prevalent’.

In County Armagh, local champions often became folk heroes. One such figure was James Macklin of Creighan, who rose to fame in the 1880s. Known for his athleticism and strength, his exploits on and off the road are the stuff of local mythology. Tales are told of Macklin leaping over horses, hopping in and out of barrels and jumping canals—sometimes while intoxicated. His most famous contest came on 24 July 1886, when he defeated Hugh Murtagh (O’Neill), Armagh’s reigning bullets champion.

THE CORK STRONGHOLD

While Ulster was the major location in the sport’s early history, County Cork became—and remains—the chief stronghold of road bowling in Ireland. During the eighteenth century the county had a significant linen industry, with some villages developed specifically for linen production. Importantly, historian David Dickson has noted that ‘Ulster weavers formed a majority of the industrial households in the landlord-sponsored enterprises at Dunmanway [and] Innishannon’ in the mid-eighteenth century and there was a preference for Protestants. It is unlikely to be a coincidence that the many locations where textile manufacturing thrived in eighteenth-century Cork align so closely with those in which road bowling remains most popular today. The cultural influence of the migrant workers clearly survived regional deindustrialisation.

The first known Cork references to road bowling appear in the 1780s and 1790s. Local newspapers were critical, condemning the sport as a public menace. In 1788 the Cork Hibernian Chronicle claimed that it endangered travellers and was marked by disorder and violence. The following decades saw some tragedies—children and adults killed by stray bowls—and calls for the sport to be suppressed. An eight-year-old boy, for instance, died near the Lough in August 1791 after he was struck on the head by a bowl. Nonetheless, road bowling remained immensely popular, especially on Sunday afternoons. It was largely a working-class pastime, deeply embedded in communities. Matches—called ‘scores’—were typically informal and local, though there were rare contests between Cork bowlers and visitors from Ulster. In April 1805, for instance, the Cork Mercantile Chronicle carried a favourable account of ‘a match of long-bowls’ between a man named Powell from the Bandon area and a soldier from County Tyrone.

Such a positive tone was unusual. After a ‘respectable lady’ was injured near Cork city in June 1807, the press renewed its hostility towards the game. Throughout the nineteenth century road bowling was consistently portrayed as a pastime of ‘idlers’ and there were persistent efforts to stamp it out. The unionist Cork Constitution in May 1829, for example, called on ‘every respectable individual in the neighbourhood where bowl-playing is practised’ to ‘remonstrate against it, or give such information to the Mayor and Sheriffs, as may enable them to have it crushed at once’.

RAILWAY AGE

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, informal challenge games between top individual bowlers became increasingly common in Cork, thanks to improvements in railways and other transportation methods, which allowed large crowds of supporters to attend. In 1887, for example, thousands watched a score between Owen Egan of Bishopstown, the leading Cork bowler of the 1880s, and Thomas Buttimer of Ballyheeda. The contest took place along the Waterfall road, with a substantial stake of £150 per side. After three consecutive Sundays of bowling, Buttimer emerged victorious.

The 1890s saw the rise of a new Cork champion, John ‘Buck’ McGrath from Blackpool in the city. McGrath cemented his reputation by defeating highly respected bowlers Jer O’Driscoll and James Barrett in July and October 1898. He remained Cork’s top bowl player into the twentieth century and became a legend among bowling enthusiasts. However, like several other notable players, McGrath’s career was cut short by poverty and emigration; after working as a drayman for Murphy’s Brewery, he emigrated with his family to San Francisco in 1902.

Attempts by the authorities to suppress the game continued. Indeed, one of my own great-granduncles—John Lane from St John’s Square in Blackpool in Cork city—served a week in prison with hard labour in August 1904 after being convicted of ‘playing bowls on the public road’ near Blarney. A seventeen-year-old street fighter and drover with previous convictions for assault and the use of ‘obscene language’, Lane was sent back to prison for another seven days that December after being arrested again for bowl-playing. In July 1906 he received yet another sentence of fourteen days in prison for ‘obstructing the public street’, which might have been connected to a score.

John Lane was a recidivist, repeatedly in and out of prison from the age of sixteen for multiple assaults, drunkenness and malicious damage, and a number of times for using ‘profane’ or ‘obscene’ language, until he joined the British army and was killed in the First World War. Regardless, his imprisonment for road bowling twice in 1904 does indicate that efforts at suppression were tangible. Players and supporters were occasionally sent to prison.

CODIFICATION

Because there was no formal organisation, little interaction occurred between Cork and Armagh until 1928, so local rivalries dominated. Reflecting on Cork in the 1920s and 1930s, top bowl player Eamonn O’Carroll recalled:

‘Woe betide any backer who supported a bowler against a neighbour; he was quickly marked. All Fairhill backed Timmy Delaney; all Blackpool supported Batna Barrett, Jim Fitzgerald, George Betson, or Jack Murphy; all Bandon backed Red Crowley or Donie Lehane; all Upton cheered the Bennetts, Mick O’Brien, Tadhg Drew, or Murphy Ban; all Pouladuff rallied behind Tiger Ahern; and I had my own loyal followers.’

Gambling further intensified these tensions. Challenge scores were played for stakes, traditionally collected from supporters of each competitor, sometimes involving substantial sums.

The founding of the All-Ireland Bowl Players’ Association (AIBPA) in 1932 marked a turning-point. Although based entirely in Cork, the association maintained informal links with players in Ulster. The AIBPA introduced a regulated annual competition where top bowlers competed through multiple rounds before reaching a Cork/Munster final. Referees were appointed, and the association became the official arbitrator for disputes.

In Ulster, the creation of the Armagh Bowls’ Association in 1952 facilitated interprovincial competition, with leading Cork bowler Mick Barry and others travelling north for scores. This cooperation helped foster a national identity for the sport. Confidence in Armagh was boosted by ‘Red’ Joe McVeigh, a skilled bowler who rose to prominence in 1946 by defeating local champion Pat Coulter.

Internal conflicts ultimately led to the collapse of the AIBPA. In late 1954 it was replaced by Ból Chumann na hÉireann (the Bowling Association of Ireland), led by Flor Crowley of west Cork, and this new organisation continued the process of codification, although the committee’s authority was not always respected in the early years. For example, in April 1956, when Crowley intervened in a dispute between Mick Barry and Denis O’Donovan (above), he was physically attacked by several supporters of one bowler. Moreover, the tarring of country roads in the period after the Second World War presented a problem for many bowlers who were used to rough roads and excelled in long lofts; some were unable to adjust. Despite such challenges, the authority of Ból Chumann became more established over time with regard to national and regional championships and tournaments. While still embedded in local communities, road bowling developed a national infrastructure.

Fintan Lane is a social historian and author.

Further reading

J. Burnett, Riot, revelry and rout: sport in lowland Scotland before 1860 (East Linton, 2000).

J. Gray, ‘Bullet-throwing in Belfast’, History Ireland 25 (2) (2015).

J. Kelly, Sport in Ireland, 1600−1840 (Dublin, 2014).

F. Lane, Long bullets: a history of road bowling in Ireland (Cork, 2005).