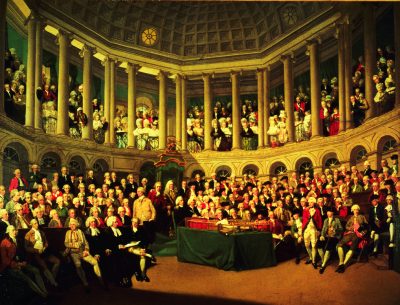

Francis Wheatley’s painting of the Irish House of Commons in 1780 is well known and has been reprinted many times. It celebrates the occasion of Henry Grattan’s speech during the debate on the rights of the Irish parliament in the spring of 1780. The painting provides a striking visual record of an important political event while at the same time capturing the sense of splendour and drama of the Irish parliament during the most important decade of its existence. The painting is divided into two sections: the lower half portrays the MPs in the chamber of the Commons, while the upper half focuses on the crowded public gallery. Some of the men in the chamber and in the gallery are, like the main figure, Grattan, wearing Volunteer uniforms. A striking feature of the painting, not often commented on by historians, is the presence of women in the gallery. A close look at the women also reveals that one of them is dressed in a Volunteer uniform, while others appear to be wearing Volunteer colours in their dress or hats. Regretfully, although we have a key that identifies most of the men in the picture, no list of the women is known to exist. We cannot, therefore, identify the woman in uniform, although we can say that she appears to be wearing the uniform of a Dublin-based regiment.

Women in the gallery

The presence of the women in the parliamentary gallery is intriguing and raises interesting questions as to why they were there and what their presence at this important debate tells us about gender, politics and patriotism in eighteenth-century Ireland. Were the women in the gallery for the social occasion, viewing the proceedings in the same way as they would view a theatrical performance, or were they more actively engaged with the politics being discussed? And why is one of the women dressed in a military uniform?

One answer to the question as to why women were in the gallery or, more specifically, why the artist, Francis Wheatley, chose to depict them in the way he did is that he was paid to do so. Wheatley was an English artist who came to Ireland in the late 1770s. His arrival coincided with the beginning of the Volunteer campaign of the late 1770s, and Wheatley quickly recognised the commercial possibilities of the Volunteer movement for an enterprising artist. The House of Commons painting is one of several that Wheatley undertook of people and events associated with the Volunteers. In November 1779 he had completed his large painting of the duke of Leinster’s review of a Volunteer regiment in front of parliament in College Green. The painting was successfully sold through public auction and purchased by the duke of Leinster, and can today be viewed in the National Gallery of Ireland. Encouraged by the sale of this picture, in the months following the 1780 constitutional debate Wheatley planned a second public painting. He advertised in Dublin newspapers his intention of composing a painting of the parliamentary debate and invited those who attended to come to his studio to sit for the painting. Wheatley charged people for the privilege of being included in the painting and planned to sell it by public auction.

Wheatley’s House of Commons painting was, however, never finished. Rumours circulated in Dublin that the painting had been over-subscribed and that more people wished to be included in it than the artist had room for on his canvas. It was alleged that Wheatley was painting over some of his earlier subscribers in order to meet the demand of later visitors to his studio.

Consequently, to evade further investigation, Wheatley was reported to have fled back to England. He seems to have taken the painting with him, and eventually it found its way to Lotherton House, a stately home in Yorkshire in the custody of the city of Leeds, where it can be seen today. A detailed examination of the painting reveals some empty seats in the chamber, presumably where Wheatley had not had the time to add his next customer.

Front row reserved for ‘ladies of the highest distinction’

The women in the gallery had, therefore, paid for the privilege of being included in the painting. Caution is consequently called for in assuming that the painting reflected the reality of the occasion during the debate. There may well be some artistic (as well as commercial) licence involved. Nevertheless, we can confirm from other documentary sources that women’s attendance in the Irish parliamentary gallery was a fairly commonplace event, particularly during important debates like that of 1780. During the debate on the constitutional legislation of 1782 Jonah Barrington estimated that there were over 400 women in the gallery. Contemporary accounts indicate that the front row of the gallery was usually reserved for ‘ladies of the highest distinction’. Wheatley also, accurately, placed most of the women in his picture in the front section of the gallery.

The story of women’s presence at Commons debates begins with the opening of the new parliamentary building in College Green in 1731. The new building was constructed to reflect the status and importance of the Irish parliament in the eighteenth century. It was also designed as a very public building in the centre of the most fashionable part of Dublin. Its layout and location indicated that it was intended to provide easy access for a select public. The main entrance off College Green, through a wide, columned open space, led into a public hall or foyer where people congregated during parliamentary sessions, often to submit petitions to be presented by sympathetic MPs to the Commons. The chamber of the House of Commons was, as Wheatley’s painting indicates, surrounded by a wide public gallery, five feet wide, which could accommodate, according to one estimate, up to 700 people, with the seated front row reserved, as we have seen, for female visitors.

Aristocratic women canvassed for political support

From its official opening in 1731 the parliament building was quickly integrated into the social scene of Dublin’s Protestant élite. When the writer Mary Delany visited the city later in the same year, she spent the best part of a day in the building. She described how she and her party arrived at 11am and heard a dispute in the Commons’ chamber concerning the outcome of an election. About 3pm they were brought chickens, ham and tongue, which they ate in the gallery, and, as she put it herself:

‘At 4 o’clock the speaker adjourned the House ’till five. We then were conveyed, by some gentleman of our acquaintance, into the Usher of the Black Rod’s room, where he had a good fire, and meat, tea, and bread and butter . . . When the House was assembled, we re-assumed our seats and staid till 8; loth was I to go away then.’

While Delany and her friends in the Protestant establishment no doubt viewed the proceedings in parliament as an interesting spectator sport, it is also important to consider the involvement of aristocratic women from landed families in Irish political life in the eighteenth century. It is a commonplace to assert that landownership and political power were closely linked in eighteenth-century Ireland, but the gender implications of this need also to be considered. Membership of a Protestant landed family automatically bestowed political influence, regardless of gender. Women as well as men canvassed for their families’ parliamentary candidates and registered and lobbied voters on the family estate. Elizabeth Hastings, countess of Moira, and her daughter, Selina Rawdon, Lady Granard, for example, were both engaged in canvassing in the constituency of Granard in County Longford in the 1780s. One potential voter described how Lady Selina visited him and noted down in a pocketbook his request for a favour in return for securing his vote. This and other similar demands were usually related to securing appointments in the public service, and potential voters clearly believed that Lady Granard had access to political influence and could secure them a position.

The fact that membership of the Irish parliament was confined to Protestant candidates meant that parliamentary politics was dominated by a small community or group of families. And the smallness of the Irish political world also facilitated women’s access to political influence. Throughout the century the House of Commons was a fairly incestuous institution, with many of the MPs being related to one another in complex family networks that often formed the basis for political alliances. In this inward-looking society, élite Protestant women had a politically influential role as marriage partners and intermediaries between the different factions.

Kept an eye on their candidate’s voting pattern

It is likely, therefore, that when women attended the debates in the House of Commons they were doing so not just as passive supporters but often as people with considerable influence over the MPs in the chamber. And, of course, attendance in the gallery meant that they could keep an eye on their candidate’s voting pattern. Jonah Barrington vividly described the impact that the women in the gallery had on the men in the chamber during the debate on the Act of Union:

‘The gratification of the Anti-Unionists was unbounded: and as they walked deliberately in, one by one, to be counted, the eager spectators, ladies as well as gentlemen, leaning over the galleries, ignorant of the result, were panting with expectation. Lady Castlereagh, then one of the finest women of the Court, appeared in the serjeant’s box, palpitating for her husband’s fate. The desponding appearance and fallen crests of the Ministerial benches, and the exulting air of the opposition members as they entered were intelligible . . . A due sense of respect and decorum restrained the galleries within proper bounds; but a low cry of satisfaction from the female audience could not be prevented.’

But it was not just as members of politically influential families that women gained access to the public world of politics. The prevailing ideology of colonial Ireland also encouraged the participation of women in political life. The emergence of patriot politics in eighteenth-century Ireland has been analysed by historians in detail, but the extent to which patriot politics facilitated women’s involvement in the political process has not been appreciated. One of the most valuable contributions on the history of Irish patriotism in eighteenth-century Ireland has been made by Joop Leersen.

He pointed out that until the 1770s Irish patriotism was primarily concerned with improving the economic conditions and trade of Ireland. The main way in which people could demonstrate their sense of patriotism was through contributing to the economic and social improvement of Ireland. So until the 1770s Irish patriotism was more about demonstrating a sense of civic awareness than railing against the evils of English colonial government. Patriotic writers and politicians promoted numerous projects to improve the trade and commerce of Ireland and to alleviate Irish poverty. A common theme in many proposals was the advancement of Irish-manufactured goods and produce. Patriotic Irish citizens could publicly demonstrate their patriotism through the purchase of Irish goods.

‘Buy Irish’ and ‘wear Irish’ campaigns

The importance of women in this patriotic endeavour was recognised by the pamphleteers. Many condemned the extravagance of wealthy women who imported the latest French and English fashions rather than support local Irish manufacturers. In 1722 Jonathan Swift specifically targeted such women in his pamphlet A proposal that all the ladies and women of Ireland should appear constantly in Irish manufactures. Swift’s publication was followed by others encouraging women to buy Irish cloth and fashions. Successive wives of lord lieutenants attempted to set a good example by making the wearing of Irish cloth fashionable, and issuing invitations to social events in Dublin Castle with instructions that only Irish-manufactured cloth was to be worn. Although such campaigns made little impact on the Irish textile industry, they did transform the wearing of Irish cloth into a symbol of virtuous patriotism. By the middle decades of the eighteenth century, élite women viewed the occasional purchase of Irish-produced textiles as an appropriate form of public charity. Patriotism thus gradually evolved into both a fashionable and a gender-inclusive sentiment.

The ‘wear Irish’ campaign was, however, more than simply a fashionable game for bored society women. It brought women into the public discourse, placed a value on their consumer power and therefore expanded their engagement with the public sphere. The patriotic Irish woman demonstrated her patriotism and her concern for the poor through the clothes that she wore.

By the 1770s Irish patriotism became more overtly political as the Volunteer campaign got under way and demanded greater political and economic freedom from Britain. The Volunteer demand for ‘free trade’ received widespread support in the late 1770s. The politicisation of the Volunteer movement coincided with a downturn in the Irish economy, which led to more calls on women to buy Irish-manufactured goods. By spring 1779 the demand for women to buy Irish cloth as an act of charity was transformed into a more overtly political gesture.

In North America, women had taken part in a boycott of British goods in order to demonstrate the colony’s unhappiness with British control of its trade. The American boycott had been very effective and the Irish Volunteers imitated the tactic by setting up a similar boycott movement in Ireland. Irish women were encouraged to follow the example of women in America. Newspaper editorials in 1779 were specifically addressed to women, encouraging them to become involved. For example, the Freeman’s Journal in September 1779 addressed its editorial to the ‘female patriots of Ireland’ and encouraged Irish women to demonstrate their sense of patriotism in the same way as the women in America. And other editorials in the same and other newspapers carried similar addresses to women to become actively involved and to manifest their patriotism publicly. By the autumn of 1779, therefore, women who had initially supported the ‘buy Irish’ campaigns for charitable reasons found themselves at the centre of a more political and anti-English campaign.

Women responded to these calls individually and collectively. In Dublin a group of women formed a non-importation association following a public meeting in April 1779, and later in the year a ‘ladies agreement’ was left in a Dublin shop to be signed by women—according to the Freeman’s Journal, it was signed by ‘a great number of respectable names’.

In addition to their public support for the Free Trade campaign, women also attended Volunteer reviews in large numbers. It was common practice, for example, for officers’ wives to appear on the reviewing stand, some dressed in the uniform of the regiment. The woman in the Volunteer uniform in Wheatley’s painting of the House of Commons was undoubtedly the wife of an officer, possibly the man standing next to her. Women were also among the crowds who cheered and waved ribbons and handkerchiefs at the Volunteers when they marched through the streets of Dublin, and they appear to have also been admitted to the convention debates organised by the Volunteers in the Rotunda in 1783.

Francis Wheatley arrived in Dublin at the zenith of the popularity of the Volunteers and quickly assumed the role of unofficial artist of the movement. His paintings document the engagement of women with the Volunteers. Apart from his House of Commons painting, Wheatley’s ‘Volunteer review’ also includes women in the windows overlooking College Green, wearing Volunteer colours, and one woman can just be distinguished dressed in a Volunteer uniform. In another Wheatley painting, that of the Stafford family at Belan House in the midlands, the dowager Lady Adleborough is dressed in a colonel’s uniform, while her daughter-in-law wears the uniform of her husband’s regiment.

The Volunteers thus provided women with new ways of expressing their sense of patriotism in public, both at the level of the officers’ wives and at the lower social level of women who participated in street protest. The Volunteer movement gave women a more visible political role than they had had before.

Reaction against women participating in public affairs

The new public role for women was, however, of short duration. By 1782 the Volunteers had been granted ‘free trade’ and some control over parliamentary legislation through the Declaration of 1782. In the 1780s the public debate moved on to the issue of parliamentary reform and, in particular, the extension of the franchise. There was disagreement as to how many and which men should be enfranchised, but none of the contributors advocated granting women any formal role in the parliamentary process. The shift of focus to parliamentary reform reduced the political usefulness of women in political campaigns. By late 1783 the involvement of women in the Volunteer movement sparked a reaction against women’s participation in public affairs, and the women who attended Volunteer reviews and the convention debates began to be mocked and scorned in Volunteer literature.

The United Irish movement that followed the Volunteers did not allot women a public role. Women were useful in the background, providing safe houses and backup support for men, but none of the United Irishmen advocated giving women a vote or more political responsibility. Some of the United Irishmen who visited France when they were negotiating for military aid wrote of their dislike of the women who participated in politics in Paris. While the Volunteer movement promoted the notion of the ‘patriot woman’, the United Irishmen did not promote the idea of the ‘republican woman’. This was to come much later in the nineteenth century.

Finally, it is worth comparing women’s engagement in politics in eighteenth-century Ireland with that of other countries. The access that élite women had to the Irish House of Commons was quite unusual, by the standards of the eighteenth century. In England in 1778, almost two years before Wheatley began his painting, the House of Commons banned women from the gallery. And in republican America after 1776 women neither voted for nor attended the debates in the inter-colonial assemblies. In France, women participated in the Revolution in 1789, particularly in the street protests in Paris. They were also initially admitted into the gallery of the National Assembly debates. But this eventually proved to be one step too far, as far as the revolutionary leaders were concerned. In 1794 women were formally prohibited from attending public debates in France. Meanwhile, back in Ireland, women continued to sit in the gallery of the Irish House of Commons—until its demise in 1801.

So, in terms of being involved in the politics of the parliament, it could be argued that women in Ireland had a more visible profile than women in other countries. The evolution of patriot politics in the 1770s also expanded the opportunities for Irish women to become involved in the public sphere. Linda Colley has suggested that it was not until the wars of the 1790s that it became socially acceptable for women in England to demonstrate their sense of patriotism in a public fashion. It could be argued, therefore, that the colonial circumstances in Ireland and the smallness of its political community facilitated a stronger political role for élite women in Ireland than in England. A more favourable comparison can be made between women in Ireland and in the other British colony, in North America. Historians have long recognised the role that women played in the American Revolution through the boycott of British goods. Women in Ireland, particularly in Dublin, were, arguably, as actively involved in the Volunteer campaign as women in North America were in the boycott campaign of the Revolution. Historians have just not recognised it.

Mary O’Dowd is Professor of Gender History at Queen’s University, Belfast.

Further reading:

A. Bourke et al. (eds), Field Day anthology of Irish writing, Vols 4–5 (Cork, 2000).

M. O’Dowd, ‘The women in the gallery: women and politics in eighteenth-century Ireland’, in S. Wichert (ed.), From United Irishmen to Union: festschrift for A.T.Q. Stewart (Dublin, 2004).

M. O’Dowd, A history of women in Ireland 1500–1800 (London, 2005).

M. Webster, Francis Wheatley (London, 1970).