MARK COEN, KATHERINE O’DONNELL and MAEVE O’ROURKE

Bloomsbury

ISBN 9781350279063

£19.99

Reviewed by Sheila Ahern

Sheila Ahern is a freelance researcher, writer and broadcaster, formerly with RTÉ (1987–2000).

In the twentieth century there were ten Magdalene laundries in Ireland, run by four religious orders. Here the editors explain that ‘by focusing on this one institution—on its ethos, development, operation and built environment, and the lives of the girls and women held there—this book reveals the underlying framework of Ireland’s wider system of institutionalization’.

The Religious Sisters of Charity ran the laundry at Donnybrook on a five-acre site (subsequently enlarged), which was in a very prominent position in the heart of Dublin 4. At one time Donnybrook Castle stood there. The prominent location challenges the myth that these institutions were hidden away. The list of customers reads like a ‘who’s who’ of Dublin 4 and beyond. Among the 900 customer accounts were Áras an Uachtaráin, the RDS, Blackrock College, Elm Park Golf Club, Fitzwilliam Lawn Tennis Club, St Vincent’s Hospital, the National Maternity Hospital, well-known restaurants in the area, and some of the local embassies and private residents from the nearby genteel Shrewsbury and Eglinton Roads.

The laundry opened in 1837 and operated under the same system, essentially unchanged, until 1992. Mark Coen contributes two chapters that trace the history of the Religious Sisters of Charity and of the laundry. The other contributors build on this solid base to create a detailed picture of how the institution ran for over 150 years.

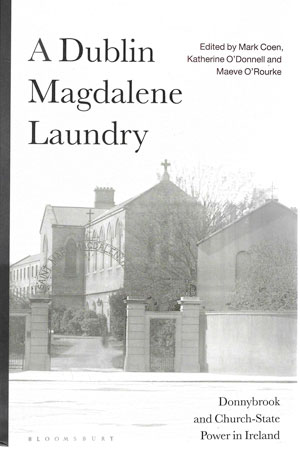

The front cover shows the entrance with the familiar wrought-iron arch and sign, ‘Saint Mary Magdalen’s Asylum’, which announced its presence. One of the misconceptions about Magdalene laundries is that they were places of sanctuary, with the use of terms like ‘home’, ‘asylum’ and ‘refuge’ giving a very benign impression. This is very effectively dismissed in the book, as are many of the misconceptions about the laundries. For example, the description of the women as ‘girls’, ‘penitents’ and ‘destitute’ obscures the reality that for many women the laundry was a place of incarceration where they worked unpaid for long hours. Lynsey Black’s chapter, ‘Women of Evil Life’, examines how some came into the laundry through the criminal justice system and were admitted under sentence, on probation or on remand. This was done on an ad hoc basis and was left up to the discretion of the judge or social worker. Much of how the laundries operated seems to have been done in a similar ad hoc vein. Some religious orders felt that they were outside the law; these laundries competed with commercial laundries for government contracts and yet they did not comply with provisions to protect workers. With pressure from trade unions, some government departments questioned the laundries’ non-compliance with the fair wages clause of contracts. In a letter to the Department of Defence, Mother Frances Eucharia refers to the women as ‘inmates’ and ‘penitents’ in an appeal for a work contract in 1941: ‘Surely it is not too much to expect our own Catholic Government will give some helping hand to a charitable institution’. Máiréad Enright’s contribution, ‘Benefactors and Friends’, describes how the nuns garnered financial support for the laundry through charitable donations and bequests. It was not unusual to see or hear advertisements appealing for donations. Enright tells us of one such appeal broadcast by Radio Éireann in a key radio slot between the Angelus and sports news in 1970.

The other chapters, by Lyndsey Earner-Byrne, Katherine O’Donnell, Chris Hamill, Brid Murphy, Martin Quinn, Laura McAtackney, Brenda Malone, Barry Houlihan and Claire McGettrick, also make significant contributions.

One of the remarkable achievements of this book is the amount of detail that the writers managed to gather without access to the archives of the Religious Sisters of Charity. The religious orders who ran so many institutions in Ireland, including industrial schools, mother-and-baby homes and the Magdalene laundries, are not obliged to give information about their operations and have resisted requests for access to their archives. The Inter-Departmental Committee to Establish the Facts of the State Involvement in the Magdalene Laundries (IDC, known as the McAleese Committee) agreed that any records given to them by the nuns would be ‘destroyed and/or returned to the relevant Religious Orders upon conclusion of its work’ (Interim Progress Report). When published in 2013, the IDC report stated that the archive they gathered ‘will be a concrete outcome of the committee’s work and may be a resource for future research’. This never happened. Maeve O’Rourke and others have made considerable efforts to access these archives without success. The order did grant Mark Coen one-day access to the Annals, up to 1920, in their archives but would not allow him to photograph the material, so he had to transcribe everything. Anyone who has done research in a library or archive knows only too well what a challenge that would be. Further access was denied on the basis that access had already been provided. The writers of this book have drawn on a wide range of material available, including newspapers, periodicals, advertisements, planning applications, published letters, the Dublin Diocesan Archive and books by the nuns.

Through the work of Katherine O’Donnell and Claire McGettrick (of Justice for Magdalene Research), the voice of survivors of the institution is given the prominence and respect it deserves in this work. As one survivor, Vera, says: ‘Ireland has woken up at long last. No more hidden secrets.’