Jane Ohlmeyer

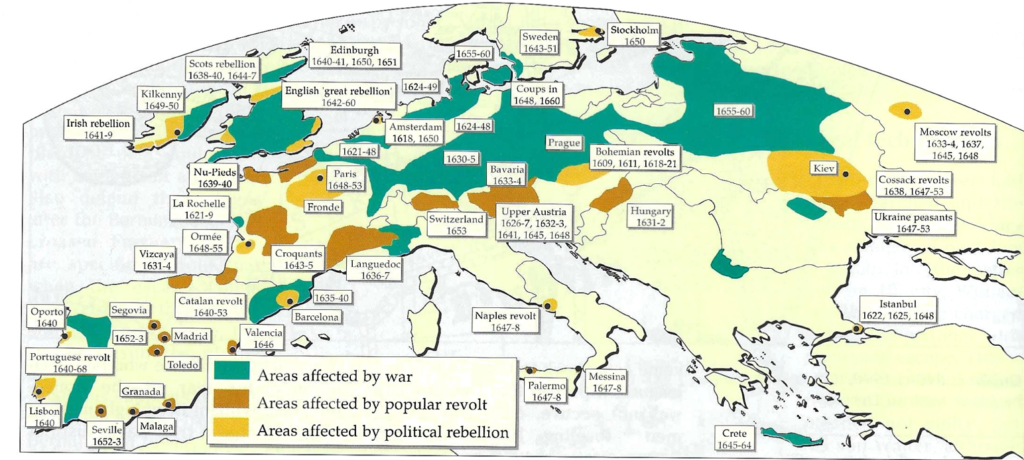

At the height of the ‘general crisis’ which gripped Europe during the middle decades of the seventeenth century, one preacher in 1643 informed the English House of Commons that ‘These are days of shaking and this shaking is universal: the Palatinate, Bohemia, Germania, Catalonia, Portugal, Ireland, England’. He could have added Scotland and the Netherlands, and by the end of the 1640s, Naples, Sicily and the Ukraine as well for, as Voltaire later concluded in his Essai sur les moeurs et l’esprit des nations (1756), this ‘was a period of usurpations almost from one end of the world to the other’. Of these ‘usurpations’ only the Portuguese, the Dutch and the Ukrainians succeeded. Even though Catholic Ireland failed to win lasting political autonomy within the context of a tripartite Stuart monarchy, its rebellion of the 1640s nevertheless ranks as one of the most successful revolts in early modern history, for, between 1642 and 1649, the Confederation of Kilkenny enjoyed legislative independence and Irish Catholics worshipped freely.

Surprise rebellion

According to accounts left by Protestant contemporaries, the Ulster rebellion of 1641 came as a total surprise: the County Tyrone MP, Audley Mervin, for one, could hardly believe that it was ‘conceived among us, and yet never felt to kick in the wombe, nor struggle in the birth’. Nevertheless the rising, which began on 22 October, plunged Ulster, and within a short time all of Ireland, into a decade of total war. Sir Phelim O’Neill and his co-conspirators succeeded in taking the key strongholds of Charlemont, Mountjoy castle, Tandragee and Newry; only Derry, Coleraine, Enniskillen, Lisburn and Carrickfergus escaped capture. From Ulster the revolt quickly ‘diffused through the veines of the whole kingdome’; by the spring of 1642 it had engulfed almost the entire country, wreaking havoc on the militarily impotent Protestant population.

The unexpected nature of the rising, combined with political unrest in Britain, proved critical to its initial success. King Charles I, already exhausted by the Bishops’ Wars of 1638 and 1639-40 against the Scottish Covenanters, became embroiled in his own struggle with the Westminster Parliament and failed to act decisively against the Irish insurgents. Had the English king accepted the Grand Remonstrance (December 1641) and somehow reconciled his differences with Parliament, there can be little doubt that the revolt in Ireland could have been quashed with relative ease; but any hope of dealing quickly with the Irish problem was thwarted by the outbreak of the First English Civil War in August 1642 which dramatically reduced the amount of English money and the quantity of supplies and soldiers available for Ireland and allowed the Catholic insurgents, now bonded by an oath of association, to organise themselves into a formal confederation, modelled on the English Parliament, with its capital at Kilkenny.

Chances of success

This wholesale Catholic involvement also greatly increased the rebellion’s chances of success. Initially the revolt had taken the form of a popular rising largely directed against Protestant colonists. In this respect it clearly resembled the Normandy rebellion of the Nu-pieds in 1639 or the insurrections which broke out in 1647 in the Habsburg kingdoms of Naples, Sicily and Andalusia, where rural unrest and urban misery created conditions ripe for revolt. However these spontaneous outbursts did not succeed because the ruling classes failed to back them. And indeed, given the initial lack of support by the Earl of Antrim, an influential Ulster magnate, and of the Old English community who were, in the words of their apologist, John Lynch, horrified by ‘this sedition’ stirred up by ‘the dregs of people, the rabble of men of ruined fortunes or profligate character’, the Irish insurrection might have suffered a similar fate. However, as the rebellion gained momentum, the leading Catholic aristocrats temporarily sank their deep-seated economic, cultural and religious differences and, in December 1641, the Old English lords concluded an uneasy alliance with the Ulster insurgents. From this point on the Irish conflict enjoyed many similarities with the other great struggles for political autonomy raging during the 1640s. Why then did the Catholic insurgents fail to take advantage of this unique set of favourable circumstances in order to win freedom of religious worship and lasting political autonomy within a tripartite Stuart monarchy?

Part of the explanation lay in the huge investment in a massive but fragmented war effort. At the height of the Irish Confederate War (also known as the Eleven Years’ War) four separate armies—loyal to the Catholic Confederates, the English Parliament, the Scottish Parliament and Charles I—operated in the field. The absence of reliable quantitative data makes it impossible to estimate accurately the size of these forces; but the few surviving musters and the numerous qualitative sources (letters, ambassadorial despatches, intelligence reports, contemporary pamphlets and newsheets) indicate that at least 45,000 men constantly served in arms throughout the decade. Shortly after the outbreak of the rebellion between 33,000 and 60,000 men fought in the Confederate, Royalist and Scottish armies; by 1649 this figure had risen to between 43,000 and 66,000 soldiers. These totals are striking, given that Ireland’s population has been estimated at around 2.1 million people. If roughly twenty per cent (or 9,000 men) of this force of 45,000 were recruited in England or Scotland, then prior to 1649 seventeen Irish men out of every 1,000 inhabitants, or nearly seven per cent of the adult male population, served in the armed forces. If accurate this would indicate that as many Irishmen, in relation to total population, bore arms in the 1640s as served in the armies of Louis XIV during the 1690s, where the military participation ratio stood at 17.6 for every thousand inhabitants and where society was much better prepared for lengthy and costly combat.

Military revolution

Larger armies were merely one feature of the military revolution which transformed early modern European warfare; other key developments included the artillery fortress, the naval broadside, reliance on firepower in combat, and the application of strategies that deployed several armies in concert. Although these innovations scarcely influenced Irish warfare before 1641, all were firmly in place only a few years later and Ireland’s military leaders mastered remarkably quickly continental techniques and technology by both land and sea, and for both offence and defence.

However any advantage which up-to-date military methods brought the combatants was soon lost because neither the Confederates, the Royalists nor the Parliamentarians (prior to 1649) appeared to possess a grand strategy for winning the war. On the contrary little or no co-operation linked the various commanders. For example, just as in the early stages of the English Civil War, the armies fighting in Ireland acted as independent units, advancing, retreating and offering battle as the opinion of the commanders and local circumstances dictated; while the leading Confederate generals constantly feuded and bickered with one another over trivial, personal matters. Inept leadership by Owen Roe O’Neill, the Earl of Castlehaven, and Thomas Preston prevented the exploitation of opportunities for strategic success against forces loyal to England in 1643-44 and 1646-47, and eventually gave first Michael Jones and then Oliver Cromwell the opportunity to win major battles in 1647 and 1649. Had the Confederates secured overall military victory prior to 1646, as they came so close to doing, the costs of reconquest in 1649 might have seemed too high, paving the way for a mediated political solution.

(Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery)

Economic factors

Military impotence alone, however, cannot explain why the Confederates ultimately lost the war. A complex combination of economic, diplomatic, political and religious factors also contributed to this failure. Economic considerations—especially poor harvests, endemic indebtedness and the loss of property through plantation, mortgage or the practice of primogeniture—helped to drive the Irish to take up arms in the first place. A lengthy war then exacerbated the situation by sparking a series of devastating commercial crises which crippled Irish trade and drained the economy of much needed specie. However the disruption varied from region to region, affecting urban areas, especially Dublin, more than the countryside and the more prosperous counties in the south and east. Naturally the economic downturn influenced the conduct of the war. On the one hand, an inability to generate sufficient food, clothing and cash undermined the Protestant war-effort and left the anti-Catholic coalition totally dependent for their survival on inadequate and sporadic English and Scottish handouts. On the other, even though the Confederates tried to alleviate their mercantile problems by minting their own coinage and encouraging trade with continental powers, their inability to place Catholic Ireland on a stable economic footing ultimately doomed to failure their bid for autonomy. By the end of 1648 the Confederates teetered on the verge of bankruptcy, unable to raise money from a country which they described as ‘so totally exhausted, and so lamentably ruined’. Finally the outbreak of plague after 1649 laid to rest any hopes of an economic revival. In this respect Ireland had much in common with Catalonia, where a shortage of coin was compounded by the fact that the revolt interrupted commerce with Catalonia’s largest pre-war trading partner, Castile, and where the plague of 1650-4 destroyed any lingering chance Catalonia still had of preserving its independence from the Spanish Crown. In contrast, a buoyant domestic economy, abundant specie and extensive overseas empires served as invaluable assets in the Dutch and Portuguese struggles for independence; while the English Parliament’s control over London and the capital’s merchant community, together with its monopoly on trade, proved critical in its struggle against the king.

(Courtesy of Alexander Lord Dunluce)

Foreign aid

Nevertheless timely foreign aid could occasionally resuscitate a wasted domestic economy or, at least, provide military hardware, veteran troops and international recognition. Thus external intervention undoubtedly contributed to the success of the revolts in the Ukraine, Portugal and the Netherlands; while Scottish assistance allowed the Westminster Parliament to win the First English Civil War in 1646 and Dutch leadership facilitated another revolution in 1688. Ultimately Spanish manpower and money did not enable the prince of Condé to seize power in France, but it prolonged the Fronde (as the civil war which began there in 1648 is known) and effectively crippled that country’s ability to interfere in European affairs. While no continental armies actually fought on Irish soil, as they did during the War of the Three Kings (1689-91), interference from abroad played a critical role in shaping the Irish revolt and transformed it from a ‘war of three kingdoms’ into a multi-national struggle involving six states—Scotland, England and Ireland, together with France, Spain and the Papacy.

English and Scottish supplies throughout the 1640s helped to sustain the Protestant cause, while decisive English intervention after 1649 reduced Ireland to English control. Even though there is no evidence linking any of the continental Catholic powers with the outbreak of the 1641 rebellion, by 1642/3, Spain—and increasingly France—became Confederate paymasters. The Irish insurgents desperately needed financial and material assistance and to that end, sent envoys to several European capitals and received accredited diplomats in Kilkenny. As the 1640s progressed, however, the desire to become Ireland’s ‘protector’ and to interfere directly in Irish politics became an aim of French, Spanish and Papal diplomacy. This helped to destabilise domestic politics and further divided the Irish political nation into the Francophiles (largely Old English), who wanted to aid Charles I in return for the best political, religious and tenurial concessions they could extort, and those (largely Gaelic Irish) who favoured Spain and advocated making Catholic Ireland, with the aid of foreign powers, impregnable to invasion from England. Thus, to some extent, Ireland had become a proxy international battleground, a minor theatre in the Thirty Years’ War then raging on the continent.

Once again, Ireland’s experiences of revolt closely resembled that of Catalonia where French intervention initially divided the rebels into those who favoured some contact with Philip IV and those determined to place the region under the sovereignty of Louis XIV. However as it became increasingly clear that France intended to use Catalonia to further her own strategic interests, continued intervention provoked widespread hostility and anti-French riots, greatly undermining the Catalan war effort.

Internal divisions

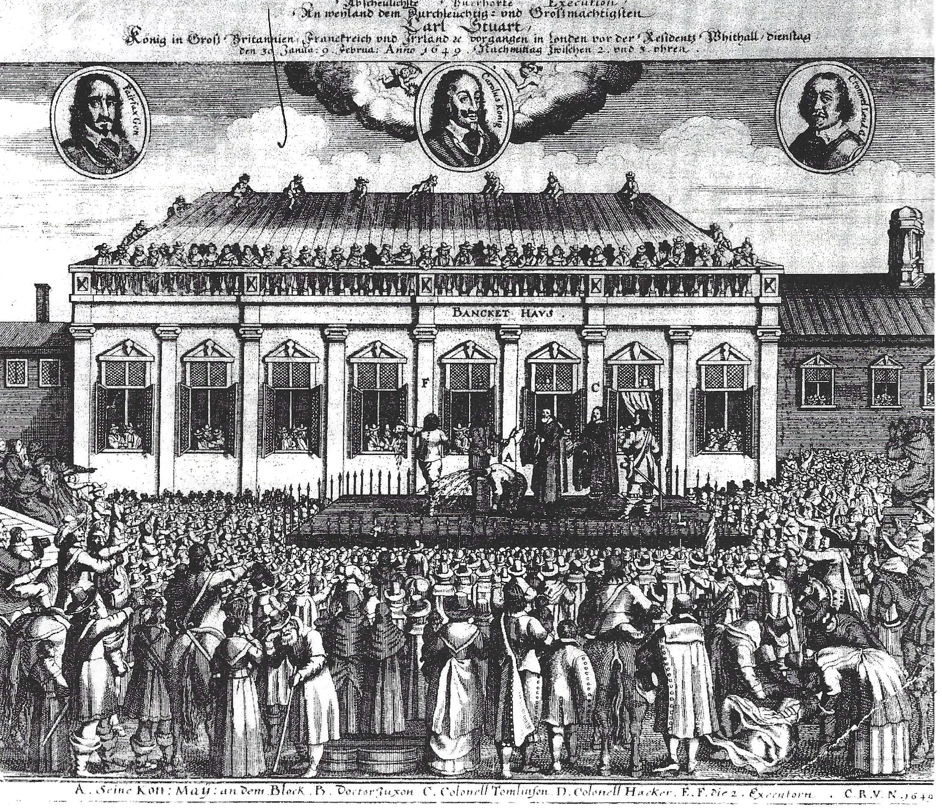

Perhaps effective political leadership and domestic harmony could have helped to overcome the formidable problems faced by the Confederates during the 1640s. Certainly a tradition of autonomy and the leads taken by the Duke of Braganza in Portugal and the house of Orange in the Netherlands enabled the Portuguese and Dutch rebels to take on and defeat Habsburg Spain, an early modern superpower. Conversely the failure of the Fronde can be attributed to a weakness of leadership and to the total lack of unity amongst the leading aristocratic, bureaucratic and judicial insurgents. Similarly in Scotland religious differences, increasing disillusionment with the Earl of Argyll’s leadership and deep divisions over whether to support the king or the English Parliament as the best means of furthering the revolution proved fatal for the Covenanters. Factional divisions also wracked the English political nation. The defeat of the Scots at the battle of Preston (August 1648), instead of fostering unity among Parliamentarians, exacerbated the animosities between the ‘Presbyterians’ and ‘Independents’ and only a determination by the army to bring Charles Stuart ‘that man of blood, to an account for that blood he had shed, and mischief he had done… against the Lord’s cause and people in these poor nations’ facilitated the constitutional revolution of 1648-9. Again, throughout the 1650s, competition between the army and the politicians for control at Westminster jeopardised the future of the English Revolution.

Similarly in Ireland internal dissension arising from divided loyalties, racial rancour and religious differences help to account for the failure of the revolution. Despite the fact that the Confederates (like the English Parliamentarians) blatantly violated the king’s royal prerogatives and consistently refused to obey his instructions, they nevertheless referred to themselves as ‘loyal subjects’ and hoped that Ireland would remain an integral part of the Stuart monarchies albeit with greater religious and political freedom. The Confederate oath of association contained the phrase ‘I further swear that I will bear faith and allegiance to our sovereign lord King Charles…and that I will defend him…as far as I may, with my life, power and estate’. Throughout the war Gaelic poets lauded Charles I as ‘their rightful king’, and saw themselves as ‘Charles’s people’. Hardly surprisingly after his execution the majority of Irish Catholics, like the Scots, viewed Charles II as his legitimate successor and in 1660, together with the Protestant community, joyously welcomed his restoration as ‘the prince of the three kingdoms’. Only a small minority of native Irish confederates behaved otherwise. The Jesuit Conor O’Mahony, for example, urged the Irish to renounce Charles I as a heretic and foreigner and to replace him with a prince of Irish blood. However these nationalist firebrands proved the exception rather than the rule; and both the Confederates and the national synod of the Catholic clergy publicly burned O’Mahony’s book.

Church or king

Nevertheless, reaching a political and religious arrangement acceptable to all parties proved predictably difficult. With the conclusion of a temporary ceasefire in September 1643, the vast majority of Confederates faced the dilemma of how to reconcile this loyalty to the king with their devotion to the church and to formulate a moderate settlement which would, in the words of the Earl of Clanricard, not cut ‘too deep an incision…into old sores’. However it proved impossible to ‘staunch and heal the bleeding wounds of this unhappy kingdom’ largely because religious differences formed the main stumbling block to the conclusion of any permanent peace between the Confederates and the Royalists which, in turn, undermined any real chance of defeating their common enemy, the English Parliament. In January 1645 Charles I, desperate for Irish aid, instructed the Earl of Glamorgan, a prominent Catholic noble from Wales, to secure Irish troops for royalist service in return for religious concessions and, the following August, the Confederates and Glamorgan agreed upon a secret treaty which involved sending 10,000 Irish troops, arms and munitions to England. Almost at once the Papal nuncio, Rinuccini, rejected the Glamorgan Treaty on the reasonable grounds that insufficient provision had been made for the Catholic religion and that Glamorgan lacked the power to implement those concessions he had granted. The following year, for similar reasons, the nuncio found yet another peace agreement, known as the First Ormond Peace, unacceptable and first excommunicated and then exiled from Kilkenny those Confederates who favoured it. Defeat on the battlefield first at Dungan’s Hill (8 August 1647) and then at Knocknanuss (13 November 1647) left an already fragmented country divided into ‘a woeful spectacle, cantonised into severall sundry factions, drawing all divers waies, and driveing on several interests’.

Myopia

Matters deteriorated further in the spring of 1648 when the parliamentary commander Lord Inchiquin declared for the king and forged an alliance with the more moderate Confederates. Rinuccini responded by excommunicating the supporters of the Inchiquin Truce, who in retaliation appealed directly to Rome against his censure. Catholic Ireland became more polarised than ever before, and the battle lines between the ‘moderate’ party and the ‘extreme’ faction were formalised on 11 June when Owen Roe O’Neill and the army of Ulster declared war on the Supreme Council. These internecine quarrels mystified foreign observers, who could not understand the myopia of the Irish:

What really surprises the majority of those who contemplate the affairs of Ireland [the French ambassador in London reported back to Paris] is to see that people of the same nation and of the same religion—who are well aware that the resolution to exterminate them totally has already been taken—should differ so strongly in their private hostilities; that their zeal for religion, the preservation of their country and their own self interest are not sufficient to make them lay down—at least, for a short time—the passions which divide them one from the other.

Similarly, frustrated Gaelic poets repeatedly bemoaned the nation’s lack of military and political unity and, like John Lynch writing in 1662, wondered: ‘Are not five hundred years powerful enough to make one people of the English and the Irish?’

Conclusion

Ultimately then, internal divisions, largely stemming from religious differences, inadequate military or political leadership and split loyalties, combined with the failure to forge a stable economic infrastructure, fatally undermined the Catholic war effort. By the later 1640s only sustained foreign aid—from either France, Spain or the Papacy—could have provided an effective bulwark to the formidable resources of an increasingly aggressive English Parliament. However war in Italy had exhausted the Papal exchequer; Venice was fighting against the Turks; internal revolts and external conflict between France and Spain swallowed up their resources. This perpetual war on the continent during the 1640s ensured that Ireland became as much a victim of the ‘general crisis’ as any other nation.

Jane Ohlmeyer lectures in Irish history at Yale University.

Further reading:

T.W. Moody, F.X. Martin & F.J. Byrne (eds.), A New History of Ireland vol. III (Oxford 1976).

A. Clarke, ‘Ireland and the General Crisis’, in Past and Present vol. 48 (1970).

J. H. Ohlmeyer, Civil War and Restoration in the three Stuart kingdoms: the career of Randal MacDonnell, Marquis of Antrim 1609-1683 (Cambridge 1993).

M. Ó Siochrú, ‘The Confederation of Kilkenny’, in History Ireland (Summer 1994).

This article is based on the introduction to Ireland from independence to occupation, by Jane H. Ohlmeyer (ed.), to be published shortly by Cambridge University Press.