By Ruadhán MacFadden

Wrestling was once a common feature of life and society in Ireland. Throughout the medieval period we see frequent literary references suggesting that it was considered a ‘must-have’ skill for any martially inclined man of the time. A young Cúchulainn quickly demonstrates his potential by effortlessly throwing ‘fifty kings’ sons’ to the ground during a game of hurling. Two opposing figures in the Táin Bó Flidhais (also known as the ‘Mayo Táin’), the warriors Leitriach and Muinceann, toss aside their ruined weapons and settle matters with ‘a wrestling bout, furious, sustained, and strong’. A similar encounter can be seen in the Cath Finntrágha (‘The Battle of Ventry’) when, during a pitched battle on the shore at Ventry, Co. Kerry, the prince of Ulster grapples one on one with a great champion of an army of foreign invaders. Likewise, the titular hero of Tóraigheacht Dhiarmada agus Ghráinne (‘The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Gráinne’) chooses to tackle one of his pursuers with nothing more than the strength of his arms:

‘[They] rushed upon one another like wrestlers, like men, making mighty efforts, ferocious, straining their arms and their swollen sinews, as it were two savage oxen, or two frenzied bulls, or two raging lions, or two fearless hawks on the edge of a cliff’.

Wrestling in Ireland was not limited to the realm of stories, though—far from it.

WRESTLING IN HISTORY AND FOLKLORE

A Gallowglass dynasty in west Donegal, Clann Mac Suibhne, once used a wrestling match to settle a leadership dispute, and generally held wrestling in sufficiently high regard to feature it on a sixteenth-century memorial slab to one of their more prominent members, Niall Mór Mac Suibhne. In Irish life in the seventeenth century, the genealogist and historian Edward MacLysaght recounts how wrestling matches were a common feature at any Irish country fair or village gathering. When reading through the great collections of Irish folklore such as Bailiúchán na Scol (the Schools’ Collection), one can see that this held true right up until the late decades of the nineteenth century. In fact, while browsing the answers provided by those young researchers’ elderly relatives and neighbours, one is struck by just how utterly omnipresent wrestling was in Irish life at that time:

‘Wrestling was common in many parts of the county 40 or 50 years ago on Sunday evenings. A crowd would gather and a ring was made. A man from one parish would go into the ring and challenge a man from another parish to wrestle against him. There would be great excitement and when a victory was gained two more from different parishes would go in. The winner of each contest would wrestle against each other until one parish was defeated.’

Such was the prevalence of wrestling skill among young men that it would often find itself expressed in other sporting contexts as well. The Gaelic games of the time were notoriously rough endeavours, and techniques sharpened in wrestling encounters—such as a quick trip to bring one’s opponent tumbling to the ground—proved just as valuable on the football or hurling pitch. Sometimes the techniques applied were less than subtle. One Tipperary player, irritated by the persistence with which he was being marked by an opposing defender, resolved the issue by simply picking the man up and throwing him over a fence!

REGIONAL VARIATIONS

When the GAA was founded in 1884, one of its first challenges was to produce a standard set of rules for Gaelic football and hurling. Before that it would have been more a case of region-specific footballs and hurlings that differed slightly across the country. Likewise, there would have been various region-specific (and likely even village-specific) approaches to wrestling.

The backhold method of wrestling appears to have been common throughout Ireland. Under this framework, the two competitors engage each other in a chest-to-chest embrace, with their arms wrapped around each other’s torsos. They then lock their hands together behind their opponent’s back and commence wrestling. They are required to keep this hold throughout the entire match. Backhold has historically been practised all across north-western Europe, with local versions being seen as far out as Iceland (hryggspenna, literally ‘back-spanning’). In the modern day, backhold wrestling is still practised in Scotland (where it is called Scottish Backhold or Highland Wrestling) and the north of England (where it is called Cumberland and Westmorland wrestling).

We cannot, of course, definitively state how people in Ireland wrestled a millennium ago, but many of the surviving literary and artistic depictions of historical Irish wrestling strongly suggest that the backhold method was quite prevalent here. Wrestlers in the characteristic chest-to-chest embrace appear on high crosses (at Durrow, for example), on a mural on the wall of Clare Island Abbey and on a sixteenth-century memorial slab in Killybegs, Co. Donegal. In Edward MacLysaght’s account of a wrestling match at a seventeenth-century country fair, he specifically describes the wrestlers engaging in what he calls a ‘hug’ position.

On the other hand, in his 1895 book Abhráin grádh Chúige Connacht (‘Love songs of County Connacht’) Douglas Hyde tells a story of a wrestling match in Sligo in which the two competitors were required to take a grip on each other’s belt (a match, incidentally, that ended in a broken back for one of the men). And from examining the accounts in the Schools’ Collection, we can see that there was very little in the way of a unified national approach to wrestling; every parish would have had its own slightly different interpretation of it.

COLLAR AND ELBOW

In the nineteenth century, however, there was one particular variant of Irish wrestling that rose to the top—not just in Ireland but also across vast swathes of the world.

On a pleasant Sunday afternoon in 1877, author Bram Stoker happened upon a boisterous gathering of men during one of his casual strolls through the Phoenix Park. The occasion was a wrestling contest. The type of wrestling, in Stoker’s words, was ‘old-fashioned Collar and Elbow’. Unlike backhold, the earliest visual depictions of which date from the ninth century AD, Collar and Elbow was a much newer arrival on the Irish wrestling landscape. References to matches under ‘collar-and-elbow’ rules start appearing in newspaper accounts in the 1820s, and by the mid-nineteenth century it had risen to become the most popular framework for conducting wrestling matches in the country. During its height in the 1850s and 1860s, Collar and Elbow wrestling matches between county champions could draw immense crowds. The Kildare journalist and passionate Collar and Elbow aficionado John Ennis estimated that one particular match in 1865 was witnessed by 10,000 cheering spectators. While Ennis’s numbers may have been prone to a touch of exaggeration, there is no doubt that contests between the strongest wrestlers were hugely popular occasions. The energetic contest that Bram Stoker came across in Dublin was a weekly occurrence, as hopeful challengers from neighbouring counties gathered to wrestle in the great open-air arena of ‘the Hollow’ in Phoenix Park.

As waves of Irish emigration intensified, Collar and Elbow was brought to the far corners of the world, and national championships were established and vigorously contested in the United States, Australia and New Zealand. And on a smaller, less-organised scale, the presence of Irish soldiers in the British army led to individual Collar and Elbow matches in places as unexpected as Malta and India. The match in the latter, mentioned in a letter to the Bombay Football Club, was specifically described as ‘wrestling, Kildare style, collar-and-elbow’. As pleased as John Ennis surely would have been with this designation, it was more common to see credit for Collar and Elbow attributed to Ireland as a whole.

RULES

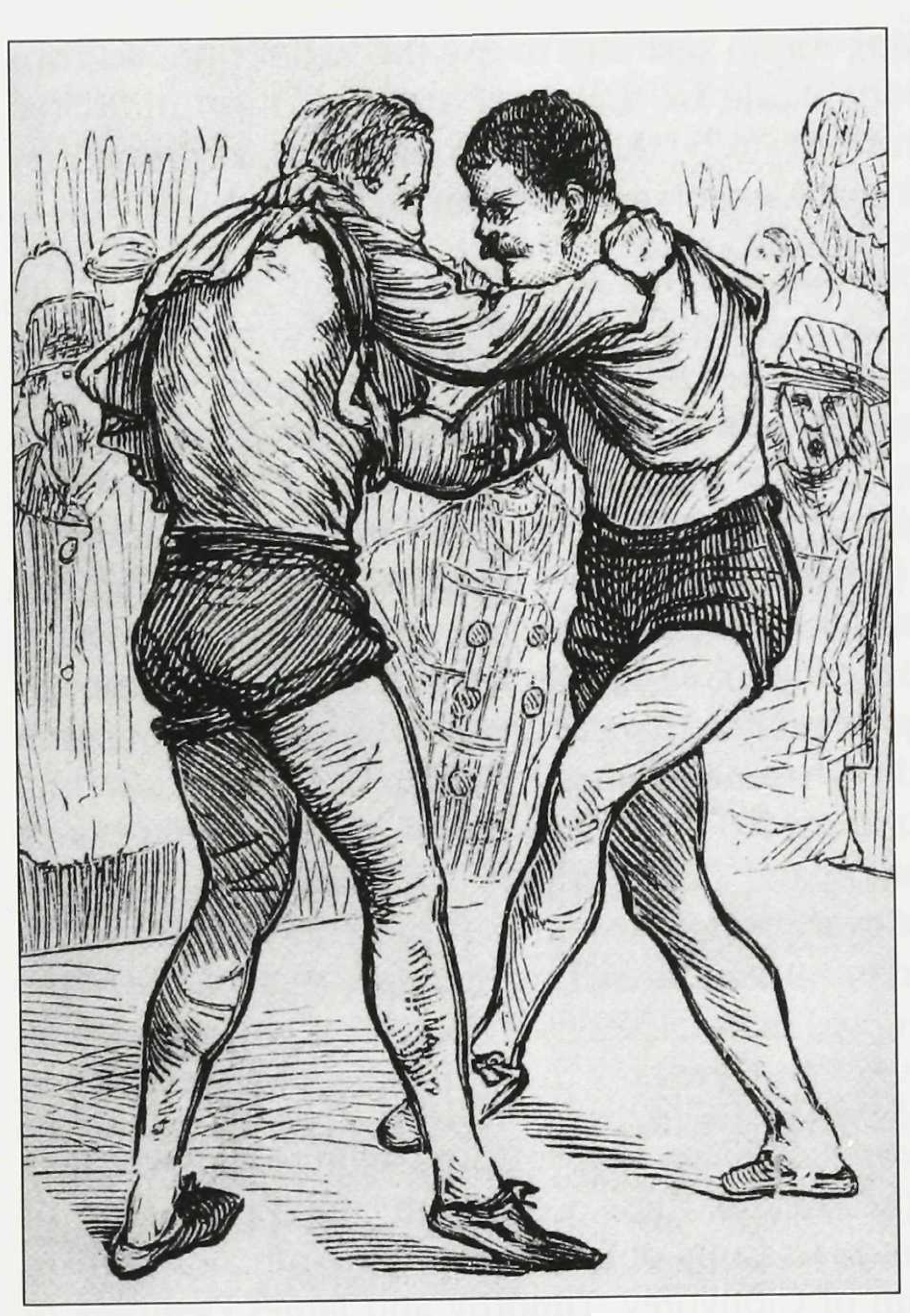

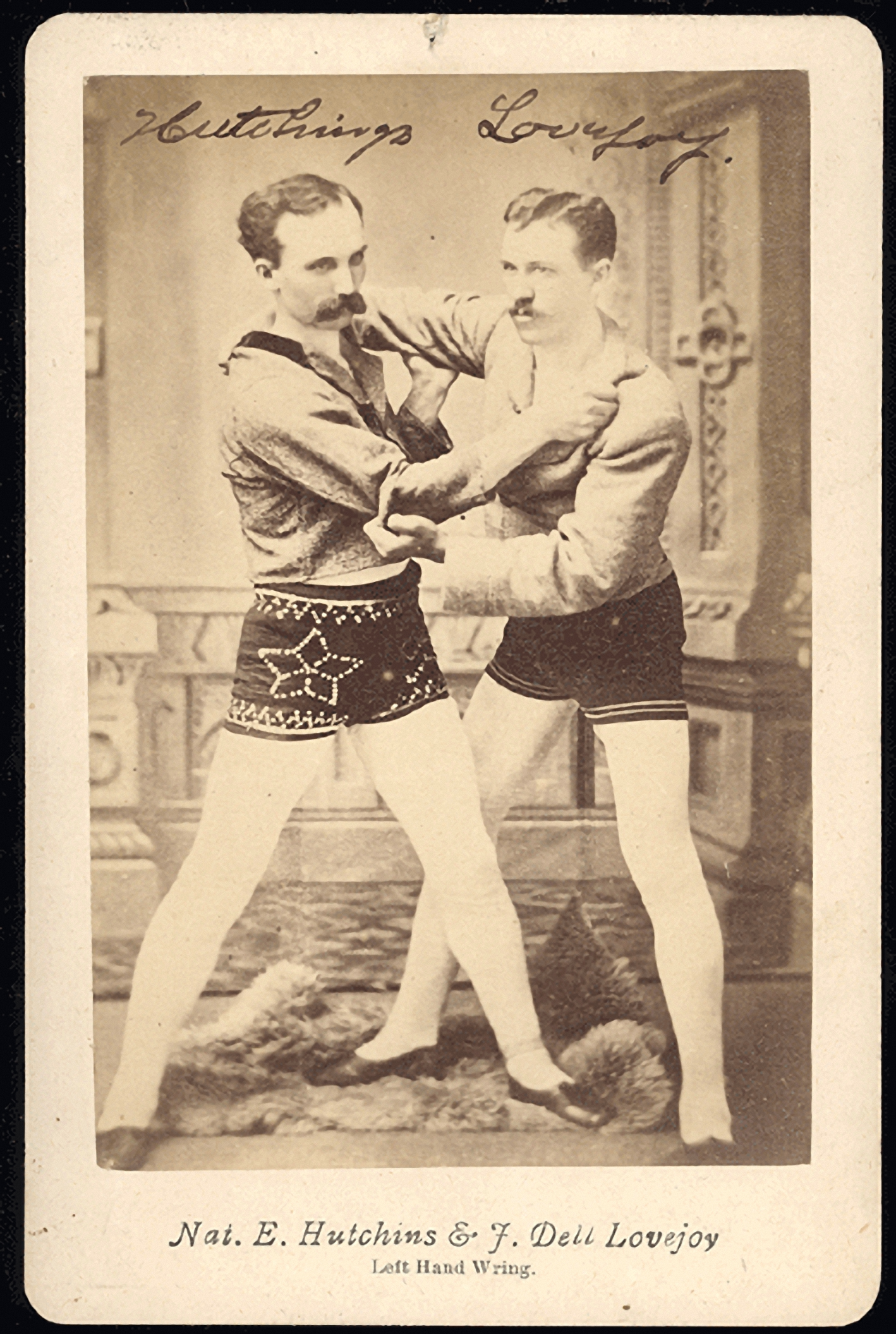

There are, unfortunately, no photographic records of Collar and Elbow matches—at least, none that have yet been unearthed. Nevertheless, thanks to the plentiful blow-by-blow accounts of matches that featured in newspapers of the time, as well as the written rules for the style that were published in the United States in the 1870s, we can visualise quite clearly what the ‘Irish method of wrestling’ would have looked like.

In the standard competitive form of Collar and Elbow, wrestlers were required to wear strong canvas jackets upon which they would take the eponymous grip (right hand on the collar, left hand on the sleeve). They had to maintain this grip throughout the entire match. Their goal was then to use their legs to trip the other man to the ground. This leg-centric focus, and the dazzling speed and precision with which skilled wrestlers would attack, led one journalist to remark that a Collar and Elbow match resembled nothing so much as ‘a fist fight with the feet’. In general, the style drew almost universal praise for its emphasis on technique, timing and intelligent strategy over sheer brute force:

‘In measuring the values of the different styles and schools of wrestling, I unhesitatingly give preference to Collar and Elbow as the most scientific and beautiful of all’.

Unfortunately, despite having quickly ascended to the top of the nineteenth-century combat-sports world both at home and abroad, Collar and Elbow would soon decline almost as rapidly. Newer, more dynamic styles of wrestling such as Greco-Roman and Catch-as-Catch-Can wrestling arrived on the scene (see Ronan Mulhaire’s ‘The wrestling rage—the world championship tournament in Dublin, 1907’, HI 31.2, March/April 2023, pp 30–3), and Collar and Elbow’s more measured pace grew less appealing to audiences. By the turn of the century it had already disappeared from the line-up of most big wrestling contests, and the ensuing decades would see it vanish entirely.

Back home in Ireland, there is a chance that Collar and Elbow might have persisted if it had been acknowledged and promoted by the nascent GAA. Unfortunately, it was barely even mentioned in the early instalment of the organisation’s rulebook, and Collar and Elbow, as well as the diverse other forms of wrestling once practised across the land, were soon lost from the Irish sporting landscape. Today they have faded from memory almost entirely.

Ruadhán MacFadden is the author of Irish Collar and Elbow wrestling (Fallen Rook Publishing, 2021).

Further reading

M. Corrigan, ‘Collar and Elbow wrestling’, Kildare eHistory Journal, 27 May 2006 (https://kildarelibraries.ie/ehistory/collar-and-elbow-wrestling/).

P.I. Gunning, ‘Hardy Fingallians, Kildare Trippers, and “The Divil Ye’ll Rise” Scufflers: wrestling in modern Ireland’, in R. McElligott & D. Hassan (eds), A social and cultural history of sport in Ireland (London, 2016).

The Schools’ Collection, available at https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/schools.