By Mark Henry

SOURCE: CSO

A century ago, with the country on the brink of a bitter civil war, the prospects for the Irish Free State (which officially came into being in December 1922) did not seem particularly bright. And any objective evaluation is compelled to conclude that the first 50 years of independence failed to produce a notable improvement in the lives of Irish citizens.

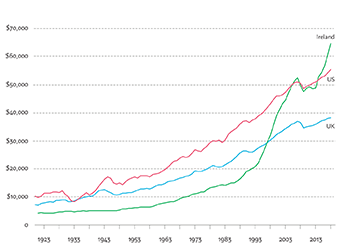

Although the new state was born into a golden era of globalisation, the Great Depression that started in the United States in 1929 led to global economic hardship and a turn towards protectionism. It was a direction that was enthusiastically adopted by the first Fianna Fáil government in 1932, with its desire to reduce reliance on Britain. In the long run the pursuance of a policy of self-sufficiency choked economic growth. Although gross domestic product (GDP) per capita increased one-and-a-half-fold between 1922 and 1972, it consistently remained under 60% of the value of that of the UK and only 40% of the value of that of the USA.

SOURCE: CSO, DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION

After no meaningful increase in the value of our exports before the 1950s, they tripled in the 1960s, although more than two thirds of them remained UK-bound. That growth, however, did not result in additional numbers in employment. The one million people who held jobs in the early 1970s represented a decline of nearly 200,000 from the number in the early 1920s.

The net result was high levels of emigration, as we know. One in every three males and females who were under the age of 30 in 1946 had left the country by 1971. Most travelled to Britain to find work, underlining our failure to have achieved true independence from the UK in the economic sense.

Our independent century is therefore one of two halves. While our emigration flows arguably gave us a global perspective and a route to greater connectivity, it was our decision to turn from protectionism and to re-engage with the global community that super-powered our republic’s fortunes.

SOURCE: MADDISON PROJECT DATABASE

Next year we will celebrate the 50th anniversary of the country’s entry into the European Economic Community. It is the milestone that marks a make-over of our world-view, the transformation of our economic prospects and the receipt of significant infrastructural investment that helped to kick-start it.

We were educational laggards in our first century, as France introduced free second-level education following the First World War, the UK after the Second World War, but Ireland not until the late 1960s. Its adoption then boomed, and the percentage of children remaining to complete their Leaving Certificate has increased from two thirds in the 1960s to over 90% today. We are now educational leaders. Half of our working-age population has completed a third-level qualification. That figure has doubled in just two decades and is one of the highest in the world.

SOURCE: OECD

Our highly educated workforce has contributed to an exponential export explosion. Our goods exports exceeded €1 billion for the first time when we joined the EEC in 1973. Today they exceed €160 billion. But the world economy has shifted towards one where services are pre-eminent, and our services exports now well exceed those of our manufactured goods, with an annual value exceeding €220 billion.

Unlike the formative years of our export economy, these exports have created real employment. Even now, as we recover from the Covid crisis, there are more people in jobs here than ever before—two and a half million of them, in fact. That employment creation has enabled us to entirely end our emigration tradition and to become a significant net immigration destination instead. That, in turn, has changed the face of modern Ireland. Nearly one of five of those living here today were born elsewhere. It is a figure that exceeds that of the UK and most other EU countries.

Ireland was once a destination for emigrants’ remittances. Almost £3 billion was sent from Britain between 1939 and 1969 through telegrams and money orders. The total was undoubtedly much higher, as official figures cannot capture the cash buried inside envelopes or passed from hand to hand. Such remittances constituted around 3% of the country’s national income in the 1950s and 1960s—roughly the same sum that the State spent on old-age pensions at the time. Nowadays, Ireland is a source country for remittances. Foreign-born residents send around $1.7 billion home annually to places such as Nigeria, Poland and India.

Our growth in income and wealth has been meaningful. Our GDP per capita bypassed that of the UK in 1997 and that of the USA in 2015. While we are well versed in the shortcomings of GDP calculations that include the earnings of multinational corporations, average weekly industrial earnings are five times what they were in the 1940s in real terms and they continue to increase.

New jobs are increasingly high-skilled: more than four in ten jobs today are so classified, up from just a quarter in the mid-1980s. The number of us with middle-class incomes is growing and now exceeds seven in ten. And the proportion experiencing consistent poverty has fallen below 6%—its lowest recorded level since just before the Great Recession. In fact, as our national wealth has increased, income inequality has decreased. The most recent available data, for 2019, showed that inequality was at the lowest level yet recorded, and far less than that in the UK or US.

The facts demonstrate that our reduced reliance on the UK, and our achievement of full independence, only truly occurred in the second half of the century. Fewer than one in ten of our export goods are now UK-bound. In 1960, nearly nine in ten of our tourists were British; pre-Covid, that figure had declined to close to one third. Our divergence in education levels, GDP per capita and income inequality mean that modern Ireland now has far more in common with Nordic nations than with its nearest neighbour.

Ireland has taken her place amongst the leading nations of the world. The United Nations rates our quality of life as the second-highest on the planet. The most recent Human Freedom Index ranks us as the world’s fifth-freest country—politically, economically and socially.

We have the fifth-highest level of satisfaction with our democracy of any country and are amongst a handful of nations that has seen this increase in recent decades. And the Irish were the happiest people in Europe in the most recent EU survey. In fact, 97% of us report that we are happy to be living here today.

The success of our last half-century has been a story of the embrace of openness and the benefits it brings. As I outline in my book, this is one of the four factors accounting for our extraordinary progress, alongside our democratic and policy stability, our strength of community and corresponding high levels of interpersonal trust, and our breadth and depth of education.

We face challenges as we enter our second century, of course. The failure to provide sufficient new housing for young people is undermining our sense of community; our economic growth has caused significant damage to our natural environment that now needs to be addressed; and government investment in higher education per student has fallen to half of what it was before the austerity years.

Furthermore, recent analyses by Robert D. Putnam and Peter Turchin highlight that periods of positive national growth typically last between 50 and 70 years before going into reverse. It is therefore vital that we nurture the factors that underpinned our success, and that we meet the reasonable expectations of our highly educated population, if we are to continue to flourish.

The facts, however, are undeniable. We have progressed a long way in the past 50 years, and we have come much further than most. In doing so, we have not merely achieved full independence from the UK but also our quality of life now exceeds that of Britain in areas as diverse as education, income, equality, health and lifespan.

Independent Ireland delivered on her promise to her people—eventually.

Mark Henry is the author of In fact: an optimist’s guide to Ireland at 100 (Gill Books, 2021). See www.markhenry.ie for more.