By Patrick McDonagh

The National Library of Ireland (NLI) is one of the nation’s leading cultural heritage institutions, charged with the safe custody of a staggering number of manuscripts of historical significance. Among its more famed collections are the literary papers of twentieth-century authors as well as material from the Irish revolutionary era, but arguably the NLI’s greatest treasures date from the Middle Ages. The superb copy of the Topographia Hibernica and Expugnatio Hibernia by Gerald of Wales (MS 700) is certainly the jewel in the library’s archival crown. These two texts provide the first detailed survey of Ireland, its landscape and inhabitants ever written and a detailed account of the English invasion of Ireland by an author who was a close relative of some of the early invaders. The manuscript also contains a fascinating map of medieval Europe, including Ireland.

The NLI holds archival treasures of a more mundane nature, too: original parchment deeds relating to medieval Ireland, c. 2,400–2,500 in number. With some small exceptions, they have been integrated into the library’s Deeds Series. Written in Latin, Anglo-Norman French and Middle English, they include a wide variety of legal and financial records that provide a wealth of information about late medieval Ireland, especially for Leinster and Munster. This regional bias is of little surprise, given that the two most extensive collections relate to the Butler earls of Ormond (from the later Middle Ages based in Kilkenny Castle) and the Dowdall family of Dundalk. Most of the deeds were produced by and for members of the English colony in Ireland, which was formed from the late twelfth century onwards. These deeds can still turn up unexpected surprises, such as the recent rediscovery of two late fifteenth-century English poems—almost certainly the oldest English-language poetry in the NLI.

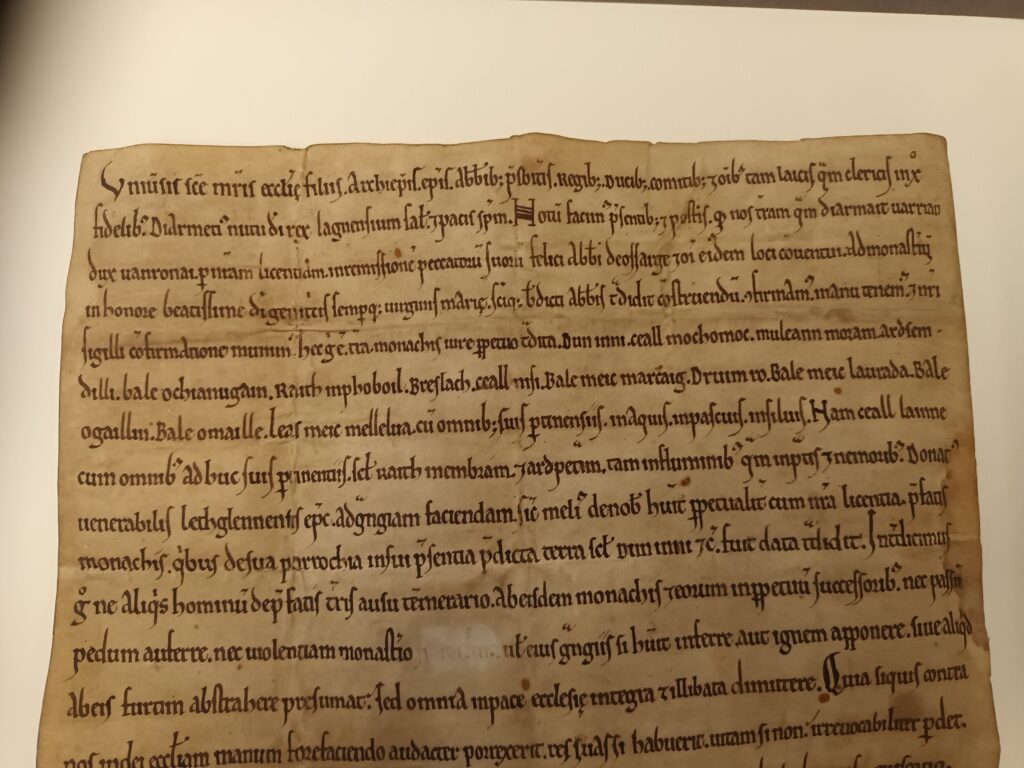

ADVENTUS SAXONUM

Though not the oldest item in the library, there is something rather fitting in the fact that the first item in the series (D.1) is a charter of the most notorious figure in medieval Irish history, Diarmait Mac Murchada, king of Leinster. Dating from the early 1160s, it records Mac Murchada’s confirmation of a grant made by Diarmait Ua Riain to Felix, abbot of Osraige, and the convent there. Though over 850 years old, the charter has survived in excellent condition. Mac Murchada is most famous as the man who invited the English (or Normans) into Ireland in a successful attempt to recover the kingdom of Leinster after being forced into exile. His daughter Aoife was married to Richard de Clare (otherwise known as Strongbow), the principal leader of the English conquistadors, who himself is the grantor of the next two charters in the sequence (D.2 and D.3).

The late twelfth-century deeds throw much-needed light on the early years of the English colony in Ireland—and do so from the perspective of some of its leading figures. Among the witnesses to Diarmait’s charter was his brother-in-law Lorcán Ua Tuathail, better known as St Laurence O’Toole, archbishop of Dublin (whose heart is still supposedly held in a reliquary at Christ Church Cathedral). By good fortune, a charter by Laurence from the late 1170s is also held by the library (D.9979); it confirms the grant of Killester made to William Brun by the canons of the church of Holy Trinity (i.e. Christ Church Cathedral). Dating from only a few years after the English conquest of Dublin, among the witnesses recorded for the charter is William Fitz Aldelm, who is described as the steward or seneschal of the king.

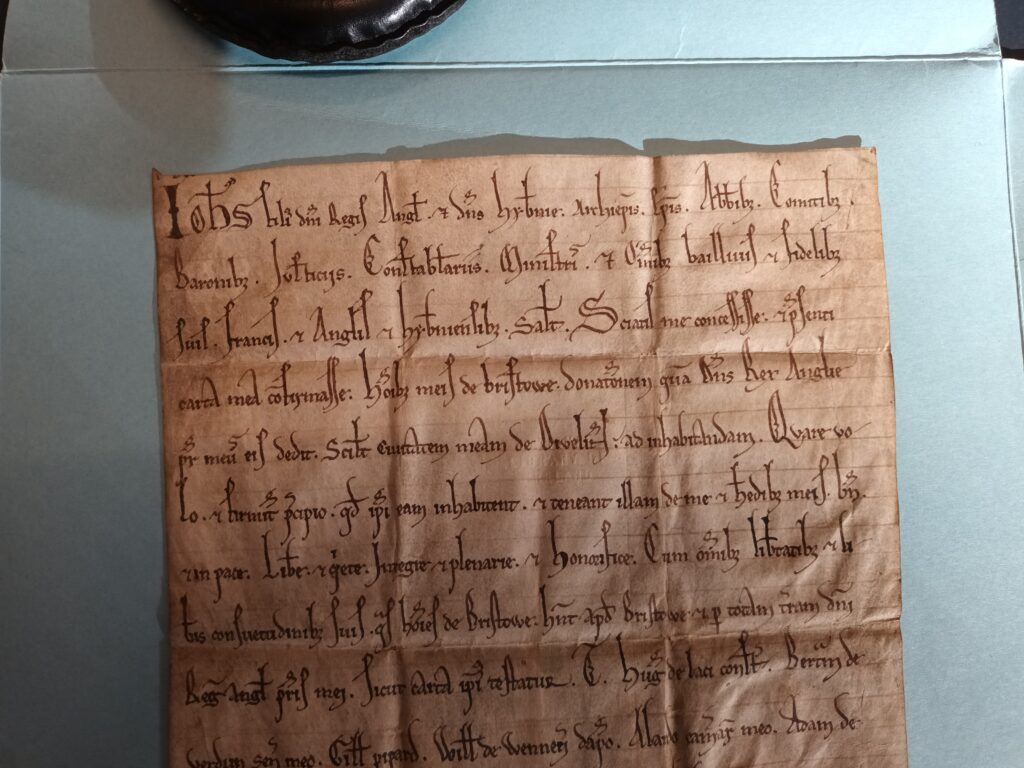

The king in question was Henry II of England, who came to Ireland during 1171–2 to assert control over both the English invaders and the native Irish kings. As part of this process, Henry took Dublin into royal control and granted the city to the men of Bristol to inhabit. Henry later granted the lordship of Ireland to his son John, who travelled to Ireland in 1185. During this expedition, John issued the third-oldest surviving civic charter relating to Dublin (D.10,018), confirming his father’s grant to the men of Bristol to inhabit the city. Owing to its early date, its timing during John’s first visit to Ireland and the list of witnesses recorded in the grant (including the powerful Hugh de Lacy, lord of Meath, with whom John fell out), it is an especially significant manuscript. At some point in its history it must have become detached from the large collection of royal charters to Dublin now held by the Dublin City Library and Archive.

SEALS

The primary importance of the deeds lies in the fact that they are written evidence dating from the medieval period itself, but it is also useful to remember that they were physical items which people would have handled and seen. For example, medieval charters, indentures, letters and other similar records would have had a seal attached to the document or imprinted on it. Seals were the primary method of authenticating documents in the medieval period, physical emblems to signify that a person or institution had agreed to the transaction involved. Moreover, they provide important visual evidence, as seals could display heraldic coats of arms or institutional symbols, as well as emblems chosen by individuals themselves.

Many of the library’s deeds still have their seals attached. Some of these have survived in magnificent condition, such as the seal of Roger Mortimer, 4th Earl of March and 6th Earl of Ulster, attached to a charter from 1397 (D.1364). Mortimer was one of the greatest landowners of his day, holding extensive estates on both sides of the Irish Sea; according to one medieval chronicle he was the declared heir to King Richard II, but he was slain in battle by the Uí Bhroin at Kellistown, Co. Carlow, in 1398. Mortimer’s seal was quartered, showing the arms of the Mortimer family and the arms of his maternal ancestors, the de Burgh earls of Ulster. The latter coat of arms has survived to become (in modified form) the modern provincial flag of Ulster.

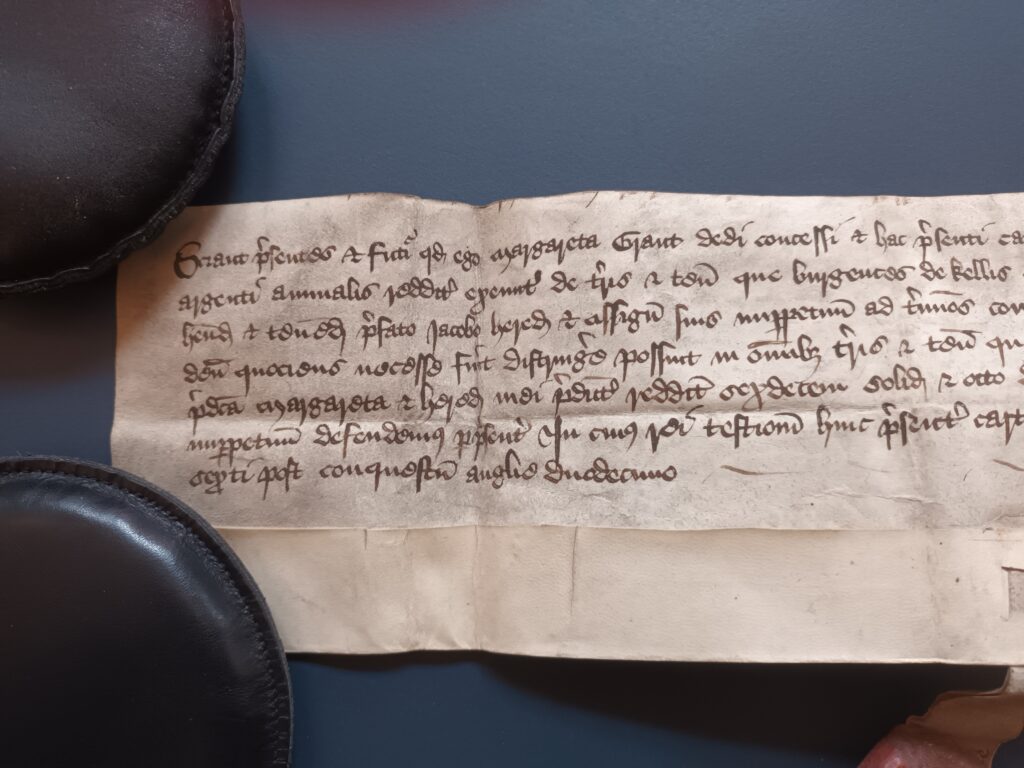

SOURCES FOR MEDIEVAL WOMEN

The deeds primarily record dealings between men, but there are many that explicitly name individual women. For example, D.1656 records a grant made in 1434 by Margaret Grant to the earl of Ormond of rents that she was owed annually by burgesses in Kells, Co. Kilkenny. Over 30 years previously, in 1399, D.1388 records that the famous Katherine of Desmond annulled a grant of 200 pounds of silver annually made to her by the earl of Ormond on condition that Ormond diligently and at his own cost acquire from the papal court in Rome a dispensation to marry her (the earl was Katherine’s uncle). According to a sixteenth-century legend, Katherine had even arranged the poisoning of Ormond’s ‘English’ (i.e. from England) wife, which must be a reference to Anne Welles. Special mention should also be made of the will of Joan (or Johanna) Whyt (D.1519) from New Ross. Joan made the will in 1406 when she was just seventeen years old. Whatever prompted these fears of early death, they were unfortunately all too accurate, as her probate was proven in 1410, only four years later.

Relatively unknown to the wider public, the original medieval deeds at the NLI deserve greater prominence. They offer a valuable window into the lives of the inhabitants of late medieval Ireland, especially those living in the English colony. The late medieval era is one of the most fascinating periods in Ireland’s history. Waves of colonisation by settlers from England and Wales inevitably altered the composition of the local population, leading to the introduction of the English language on the island and the formation of many new urban settlements. Its legacy for present-day society cannot be gainsaid. In a certain sense, it was set in motion by accident—the unintended consequences of the ambitions and actions of Diarmait Mac Murchada, king of Leinster and grantor of D.1.

Dr Patrick McDonagh is a research student in the National Library of Ireland.

Further reading

M.T. Flanagan, Irish royal charters: texts and contexts (Oxford, 2005).

R. Frame, Colonial Ireland, 1169–1369 (Dublin, 1981 & 2012).

G.H. Orpen, Ireland under the Normans, 1169–1333 (Dublin, 1911–20 & 2019).