By Isadore Ryan

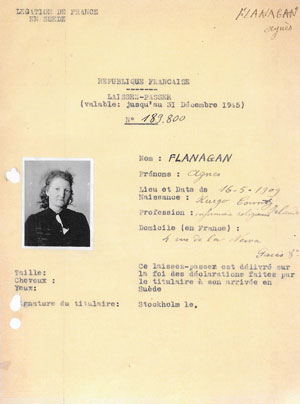

Margaret Flanagan, known as Agnes, was born in Birr army barracks on 16 May 1909. Her father, Augustine Flanagan, a private in the Leinster Fusiliers, died from tuberculosis six years later, aged 42. Her mother Kate (or Catherine, née Parsons), considerably younger than Augustine, was still living on Military Road in Birr in 1932.

In 1930, when she reached 21, Agnes set off for Belgium to work as a charwoman in a manor house near Namur. She stayed there for less than two years before turning up in Tournai near the French border, finding work there as a chambermaid. In 1934 she joined the Congregation of the Sisters of Saint Augustine, known as les soeurs noires because of their black habit, which was historically connected to caring for the sick. Agnes Flanagan was then set to work as a nursing sister under the name of ‘Soeur Augustine’ at the Hôpital de Notre Dame, just opposite the congregation’s convent in Tournai.

GERMAN INVASION AND RESISTANCE

On 16 May 1940 Tournai was heavily bombed and was occupied the next day by the Germans. Tournai is the seat of a diocese covering much of southern Belgium with a strong Catholic tradition. Quite quickly, some clerics started to oppose the invaders, most prominently Abbot Adolphe-Joseph Dropsy, teacher in a local school. Flanagan may have been influenced by these efforts, but it appears that her ‘resistance’ was a solo effort.

Agnes was first arrested on 16 September 1941 when, according to police documents, she was sentenced to eighteen months’ imprisonment in Mons for hiding an escaped British prisoner of war. Illness led to her transfer to the local hospital in July 1942, and she was back in Tournai by the end of that month, with an obligation to report frequently to the Kommandatur. She was re-arrested, however, in September of that year—this time for possession and destruction of Resistance documents.

Her second arrest had grave consequences, leading to her deportation from Belgium. After being initially detained once more in Mons, she was transferred to Saint-Gilles prison in Brussels and then to Germany. A Verfassung Sondergericht (special constitutional court) in Essen condemned her to imprisonment in Ravensbrück, where she arrived on 5 December 1942.

RAVENSBRÜCK CONCENTRATION CAMP

Precious little evidence of Agnes’s experiences in Ravensbrück remains. Like most of the other women, she would have been used as forced labour, perhaps in the surrounding forest or the Siemens factory attached to the camp. In a letter sent to a stepsister at Easter 1946, she wrote that ‘It is a dreadful time for me this Holy Week … On that Thursday last year, I was destined for the gas chamber on Good Friday morning.’ The reference would seem to be to an incident on 30 March 1945 when a number of detainees were singled out and put on waiting trucks destined for the gas chambers. As many as 2,500 women died in gassings right through Easter weekend 1945. Instead, however, Agnes was put on one of the Swedish ‘white buses’ that rescued women from Ravensbrück shortly before the German capitulation, arriving in Malmö in southern Sweden on 26 April 1945. George Clutton at the British embassy in Stockholm reported that Flanagan was

‘… not interviewed as she has gone to the convent at Drottningholm prior to her return to Belgium. She has been reported as being very nervous but her fellow prisoners speak of her with greatest admiration as being one of the bravest women in the camp.’

In June 1945 she was brought to Paris, from where she made her way back to Tournai.

Flanagan remained with the soeurs noires until December 1947, and then married Emile Depret, described as a bargeman, in April 1948. A year later, a daughter called Rose was born to the couple.

PENSION APPLICATION

Flanagan had a hard time gaining recognition as a political prisoner and the pension that came with it. In January 1949 her husband petitioned the king of the Belgians in a bid to have her case expedited. Pointing out that Agnes had been naturalised thanks to their marriage, Emile Depret wrote that ‘she has neither the pension nor the medical attention her state of health requires’. He also wrote to the state commissioner presiding over pension claims with a more direct plea for his wife ‘to receive some money as soon as possible. I am unemployed and she is sick. She needs clothes for the winter, which I cannot afford.’

These letters may have revived Belgian bureaucracy’s interest in Agnes’s case, for in March 1949 she received a questionnaire from the state commissioner in Charleroi. A clearly exasperated Flanagan replied in less-than-flawless French that she had already answered the same questions several times already, but her reply also contained details as to why she had problems convincing the authorities of her claim’s validity. ‘As I have told you over and over, I was a religious caregiver at Tournai civil hospital’, she honestly wrote, ‘and it was impossible for me to be part of a resistance group or to help or to be in contact with one.’ She explained that the Germans had condemned her simply for her refusal to submit to their authority, for hiding POWs and helping POWs to escape and for suspicion of being involved in espionage, even though they had no proof.

To back up her claim for compensation rights, Flanagan gathered attestations from different parties, including one from a fellow Ravensbrück survivor, the Czech Vlasta Stachová, who wrote that Flanagan’s ‘conduct … had been irreproachable and she always gave her help to all those misfortunates in need’. Yet when Belgian investigators interviewed a fellow detainee in Mons prison, as well as the prison chaplain, the head of Tournai hospital and the mother superior of Agnes’s congregation, none knew anything about Flanagan’s resistance activities.

In a statement to the judicial police in April 1949, the head of welfare provision in Tournai, Ludovic Deprez, gave the most detailed information yet on the reasons for Flanagan’s initial arrest in 1941 (but managed to confuse the chronology of her successive detentions):

‘She had been in contact with a British prisoner of war who looked after repairing the Germans’ cars and lorries. When the Briton escaped, Agnes Flanagan was bothered by the occupiers, but was not arrested right away … The first arrest was around May 1941, when German police turned up at her room. Flanagan tore up some papers that she threw out the window. I witnessed this gesture. Her room was decorated with photos of Churchill, De Gaulle etc. … She was released on health grounds, then resumed her service but was re-arrested on 16 September 1941 … Flanagan was very patriotic and always a model in terms of resistance … I cannot provide any precise example of resistance as the said person was not loquacious.’

The judicial police discovered that a British POW called Brown had indeed worked as a mechanic for the local German garrison. Brown moved freely around town and had gone to the local hospital after a work injury. When he disappeared around May 1941, a French–English dictionary belonging to Flanagan was found in his room at the local Kommandatur. On 16 September 1941 the Gestapo arrived at Tournai hospital to check Flanagan’s papers, the investigator reported. The Irishwoman refused to cooperate, leading to a search of her room. One of the Germans found a sealed letter in a drawer, only to have it snatched out of his hands by Flanagan, who immediately tore it up into little pieces. ‘She even cursed the Germans … and refused to give them the fragments of the letter’, which, according to the investigator, ‘contained details of this nun’s moral life’.

The Belgian investigator ended his report with the following lapidary judgement: ‘She is not known to have undertaken any form of resistance or espionage. It does not appear that she had anything to do with the escape of Brown … Flanagan was known for being unwilling to submit to the occupier for even the slightest thing.’ In September 1949, Flanagan’s husband wrote again to the state commission, this time to explain that, having just given birth, Agnes was too weak to attend a hearing in Charleroi. Flanagan herself wrote over a year later to turn down a summons to another hearing, explaining that her baby had died, that she did not feel strong enough to take the train and that she would find it difficult to scrape together the train fare, having had to borrow money to buy coal to heat her home.

In April 1951 the state commission concluded that Flanagan did not meet the conditions to gain the status of political prisoner. Flanagan appealed and for the first time explicitly claimed that she had provided one English escapee with a suit, some money and a French–English dictionary. In another declaration, Flanagan stated that the letter that she had snatched from the German officer back in September 1941 contained a list of Belgian traitors confided to her for transmission to the Allies. Flanagan’s appeal was accepted in May 1952, prompting her lawyer to request a month later that the pension owed her be paid as rapidly as possible ‘since this person is not in a comfortable situation’.

Widowed in 1970, Agnes lived alone in a small, terraced house on the rue de Barges in Tournai until her own death in August 1986. With nobody to renew the fee due, her burial plot in the Cimetière du Nord was ‘recycled’, and so no trace of her existence in the town remains.

Isadore Ryan is a writer and financial editor based in Geneva.

Further reading

S. Helm, If this is a woman. Inside Ravensbrück: Hitler’s concentration camp for women (Boston, 2015).

M. Renault, La grande misère (Lincoln, 2013).