NATIONAL GALLERY OF IRELAND (UNTIL JANUARY 2025)

By Donal Fallon

Despite being something of a lapsed Roman Catholic, I spend a considerable amount of time visiting churches. At St Joseph’s in Terenure, the stained-glass windows by the Harry Clarke Studios have inspired a history by Patricia Curtin-Kelly. A visit to Dún Laoghaire offers a chance to see Imogen Stuart’s striking depiction of St Michael the Archangel in the church of the same name. As the beautiful website www.gloine.ie reminds us, there is also a legacy of artistic intervention and stained glass in our Church of Ireland buildings, searchable online by diocese and artist. In fact, the largest patrons of the arts in Ireland were once its churches.

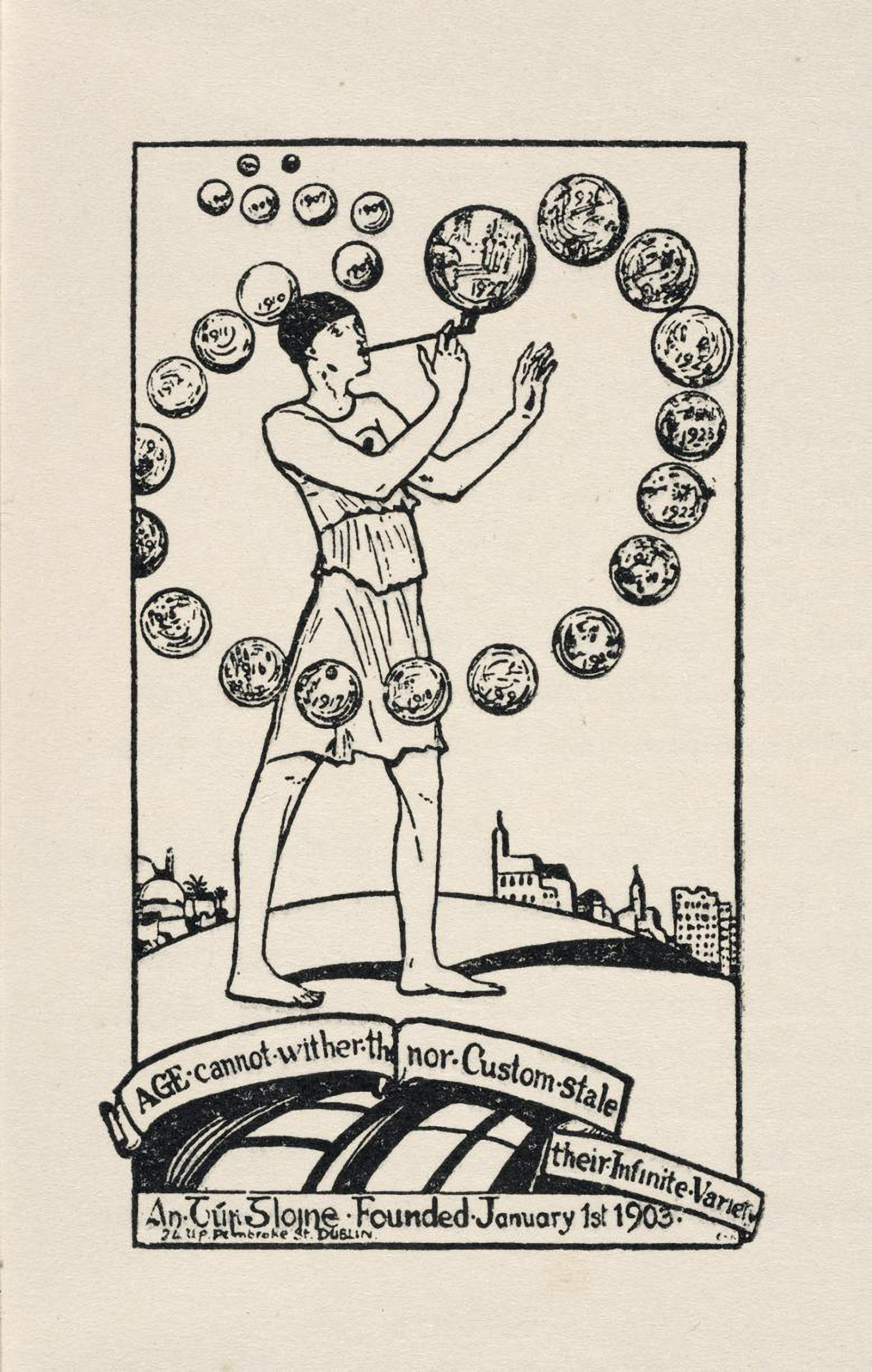

Room 11 is a small space within the National Gallery of Ireland (NGI), feeling almost like a connecting joint between its large-scale temporary exhibition space (at the time of writing hosting Women Impressionists) and the more permanent collections. Despite being a small space, it hosts paper-based exhibitions that draw from the library and archive of the NGI and has proven to be one of the most versatile spaces in the gallery. The recent Roller-skates and Ruins spotlighted artists active against the backdrop of the revolution (the curious name was in honour of Grace Gifford Plunkett, who requested her friend William Orpen to send her roller-skates into Kilmainham Gaol). Now, An Túr Gloine: Artists and the Collective shines a light on the artists who made up the pioneering stained-glass studio founded by Sarah Purser in 1903.

Remarkably, this is the first stand-alone exhibition dedicated to this collective of artists. It comes not long after David Caron’s warmly received biography of featured artist Michael Healy and the revision of the landmark text Gazetteer of Irish stained glass. Curated by Marie Lynch, the exhibition features three curated rotations, designed to protect works on paper held in the archive of the NGI. As such, it encourages repeat visits. Another unique dimension to the exhibition is that, while Room 11 may be a limited physical space, QR codes throughout the room encourage the visitor to explore ‘An Túr Gloine in our Neighbourhood’, a self-guided tour that brings the visitor to places like St Ann’s Church on Dawson Street (home to particularly impressive windows by Wilhelmina Geddes) and to other cultural institutions.

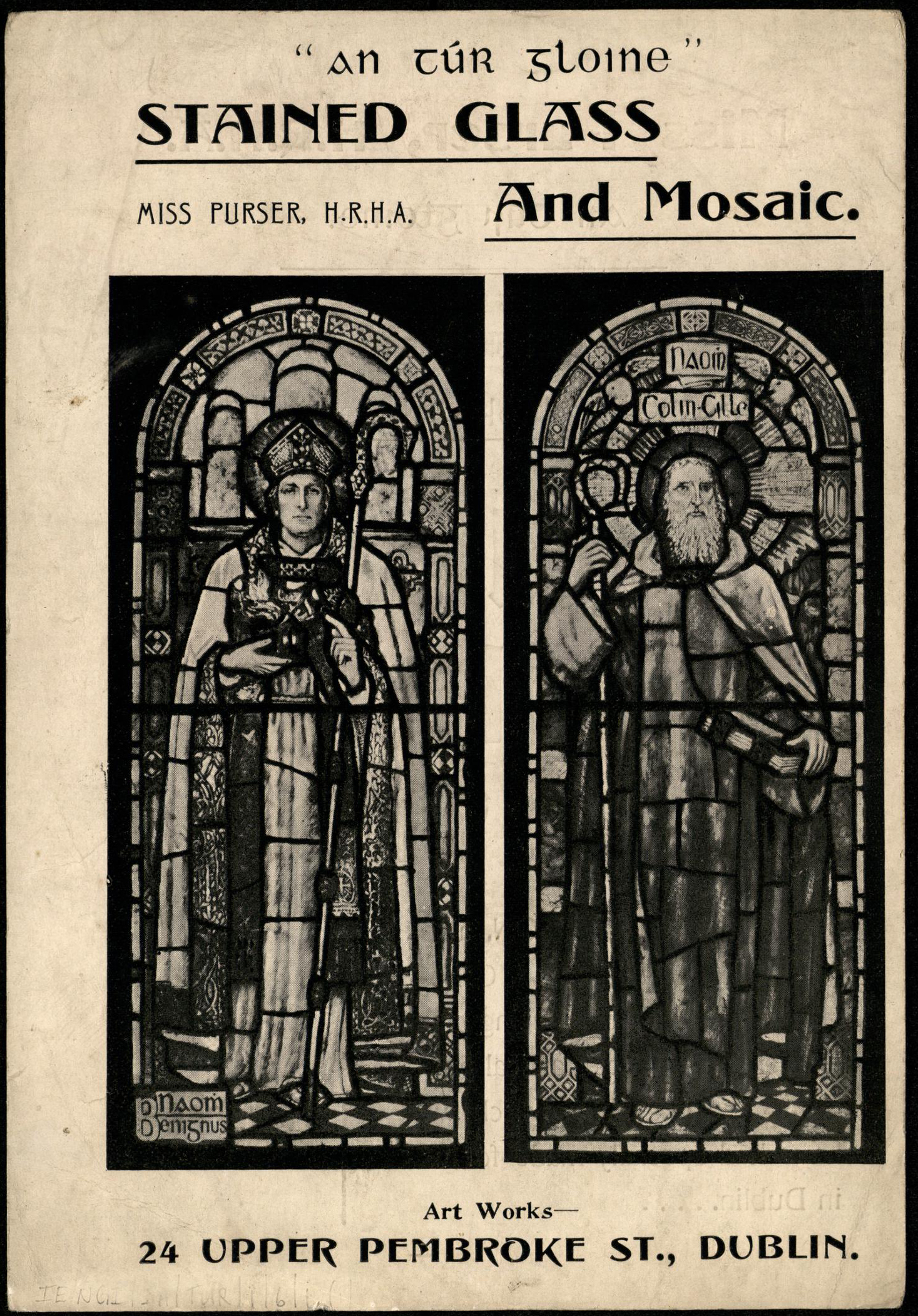

Many of the paper materials that form this exhibition were donated by Patrick Pollen, the London-born artist who was moved to work in the medium of stained glass by the deep impression made on him by the work of Evie Hone. These materials include minute-books, advertising booklets and design sketches for windows, all of which give a good overview of the day-to-day running of such a collective. More than just a working collective, we learn that An Túr Gloine was run on a cooperative basis, and officially incorporated as a Cooperative Society in 1925.

An Túr Gloine was, we read, ‘a predominantly female enterprise’. Alongside the more familiar names of Evie Hone and Beatrice Elvery, the exhibition also acknowledges the importance of Catherine O’Brien, Wilhelmina Geddes, Ethel Rhind (we see Rhind’s design for St Brigid Performing a Miracle) and others. There are other important contexts to its work, too; while the cooperative ‘by its very name … embodied the cultural-nationalist aspirations of the Gaelic Revival’, there is a strong thread of other inspirations here. We learn that the studio manager, A.E Child, ‘was a former assistant to Christopher Whall, father of the British stained-glass revival’. The Arts and Crafts movements and philosophies of other places influenced the approach of the studio and its designs, even if its output was shaped by uniquely Irish concerns.

Not all stained glass produced in Ireland had religious themes. Amidst the paper archival materials, a number of small stained-glass pieces are displayed, including é Finito, produced by Michael Healy in 1929. The exhibition describes a piece in which ‘a horse feeds contentedly from a vivid green nosebag, while the cabman dozes peacefully under his hat’. Throughout his life one of Healy’s other great artistic passions was his sketched series of everyday Dubliners going about their lives, and there is certainly a reminder of that work in this piece.

Complementing the historical research and materials is the work of Jozef Vrtiel, who specialises in photographing stained glass. Vrtiel’s work is familiar from Caron’s Healy biography and other works in the field. The (normally noble) attempts of cameras to provide balanced images with average exposure makes photographing these artworks incredibly tricky, but Vrtiel has emerged as the leading photographer in the field, chronicling this heritage as it currently stands across the island.

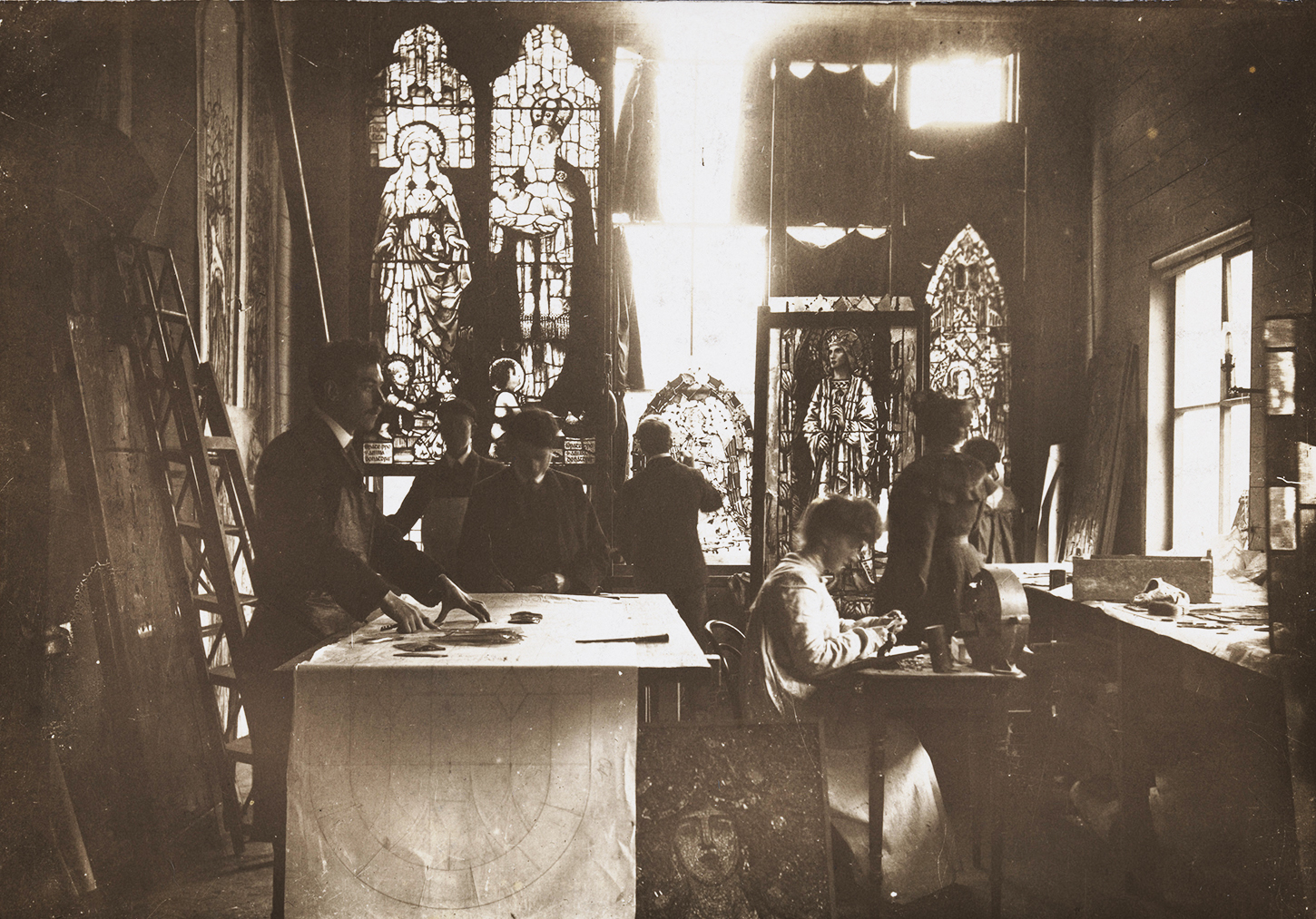

On the day I visited, a young museum attendee asked his accompanying parent a good question: ‘How did they do it?’ Archive footage from the collection of the Irish Film Institute shows the process of stained-glass production and is a reminder of how our museums and galleries are increasingly collaborating with other institutions and collections. At the James Connolly Centre in Belfast, a dedicated space draws on the holdings of RTÉ Archives, while the IFI’s collections are also being incorporated into a variety of exhibition spaces. The 1950s Hallowed Fire: The Art of Evie Hone from the IFI shows practitioners at work, while a panel describes the roles of artist and glaziers in the cutting, painting, firing and glazing of any work.

What became of An Túr Gloine? Following Sarah Purser’s death in 1943, the cooperative was dissolved in the following year. Artist Catherine O’Brien would purchase the studio for just £235, establishing a successful solo practice and, we learn here, ‘designing colourful windows for churches in Florida, Kenya and throughout Ireland’. Like O’Brien’s work, the story of Irish stained glass extends beyond just the island of Ireland. There are many beautiful works in Irish gallery and museum settings, and others abroad. With news of a forthcoming Harry Clarke Museum for Dublin’s Parnell Square, expect to hear plenty about The Geneva Window in the months and years ahead.

Donal Fallon is the presenter of the ‘Three Castles Burning’ podcast and the author of Three castles burning: a history of Dublin in twelve streets (New Island Books).