By Angus Mitchell

‘Where does Irish history begin?’ was the title of an essay published by Eoin MacNeill in 1904. This was an easy question to ask but harder to answer, and one that he spent much of his academic career elucidating. One acknowledged beginning might be traced through the temporal and spatial dreamtime of early Irish literature to Uisneach, a hill in Westmeath, just west of Mullingar.

A SACRED LANDSCAPE

During the first quarter of the twentieth century Uisneach was elevated in the national imagination to become part of a sacred landscape for those engaged in the Cultural Revival. Its significance was unearthed in the flow of edited translations of early medieval Irish texts—John O’Donovan’s Annals of the Four Masters (1856), Whitley Stokes’s Tripartite Life of Patrick (1887), Standish O’Grady’s Silva Gadelica (1892), Kuno Meyer’s telling of ‘Mongan’s Frenzy’ and, most prominently, in Edward Gwynn’s The Metrical Dindshenchas (1906–35). As the symbolic centre of Ireland, Uisneach had a deep history of ritual and ceremonial use as a demesne of Druidic culture and later as a royal seat of the southern Uí Néill. For Revivalists, it became a place of assembly symbolising cultural unity and was humorously described by James Joyce as a ‘mountainy molehill’.

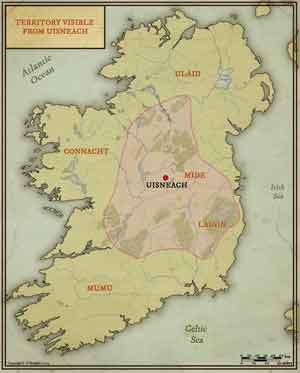

During 5,000 years of occupancy, Uisneach can be recognised as a threshold between mythological time and the earliest moments of recorded history. Sites on the hill were associated with an early fire cult and it had deep connections with the deities of the pre-Celtic and Celtic worlds, such as Dagda and Lug. The Ail na Míreann—the Stone of Divisions—was the great erratic rock, weighing over 30 tonnes, where the provinces of ancient Ireland met. And beneath the stone resided the spirit of Ériu, the sovereignty goddess, who gave her name to Ireland.

From the top of Uisneach you could quite literally ‘see’ history. Eoin MacNeill remarked:

‘Uisneach is worth a pilgrimage. You remember my saying how the Connachta, the race of Conn, after the wars of Táín, crossed the Shannon and established their power in mid-Ireland. After that they seized Tara, then Oriel or mid-Ulster, then western Ulster, & so came to dominate Ireland for six or seven centuries. When you stand on the hill of Uisneach, you get the topographical sense of all that progression remote as it is in time. The Shannon is in view & the plain of Meath is all around you. The hill is a mere swelling rise in the plain, covered with rich grass to the top, the kind of place where the old kings liked to be.’

The Cultural Revival demanded both a re-imagining and re-embodiment of history. The movement was rooted in the realisation that meaningful social change must begin with a realignment of the language through space and time to configure with a new vision for Ireland. From the founding of the Gaelic League in 1893, ancient sites were reclaimed in a deliberate move to awaken memory and to enable the telling of alternative histories as part of the resurrection of national being. Landscape became a reservoir or entry point for earlier iterations of Irish civilisation, vernacular historiography and a proto-nationalist consciousness.

12 AUGUST 1906

The revival of Uisneach was initiated on 12 August 1906. This was chosen by the Dublin Coiste Ceanntair for the Gaelic League’s annual field trip, Oireachtas turas. There was plenty of press coverage about the ‘storied hill’, billed as ‘a place of great sacred significance … woven through the most glorious epics of our literature’, in anticipation of the event. A special train was scheduled to leave Broadstone Station and stop at Castletown Geoghegan, whence it was a five-mile walk to the hill. Hundreds of passengers, many on bicycles, descended on Uisneach that day.

Distinguished participants included Arthur Griffith, fresh from the founding of Sinn Féin, and the historians Mary Hayden and Alice Stopford Green. The poet and Irish teacher Alice Milligan travelled from Antrim via Emain Macha (Navan Fort) in County Armagh. By the early afternoon a crowd of several thousand had gathered on the summit around the spot called St Patrick’s Bed. The opening address was by the barrister and Gaelic Leaguer George Moonan, who had written a pamphlet in Irish for the occasion. His narrative located Uisneach within the early mythological cycles of the Red Branch Knights and spoke to the vitality of the hill over centuries as a site for national assemblies and religious congregation.

The next two speakers spoke in Irish: Dr Donal O’Lynch, a veteran of the St Patrick’s Battalion of the pope’s army and the Franco-Prussian War (1870), and P.T. McGinley (1857–1942) (a.k.a. Cú Uladh/the Hound of Ulster), another committed Gaelic League organiser, whose house in Belfast hosted the first meeting of the Ulster branch of Conradh na Gaeilge in 1895. There followed two Westmeath antiquarians, James Tuite and James Woods. Tuite, a jeweller and clockmaker by trade, was a distinguished member of the Royal Society of Antiquaries. James Woods was a journalist who was on the point of publishing his thoroughgoing Annals of Westmeath: ancient and modern.

Speeches were followed by the Aeridheacht, an open-air platform for the performance of music, song, dance and recital. An effusive report appeared in the Westmeath Examiner (18 August 1906):

‘Is it too much to think that when night fell the shades of these ancient kings and warriors, minstrels and wisemen who had trod the hills and dales there in the bye gone centuries gathered once more on Uisneach crowded around the old stone and rejoiced that the chains of the Past had been taken up and linked to the Present by that day’s events’.

The comment touched on the significance of Uisneach as a threshold linking the continuities of sacred chronology and deep history to contemporary aspirations for sovereign independence.

THE FEISEANNA OF 1910 AND 1911

Following the 1906 event, Uisneach revived as a space for cultural assembly. In the imagination of the Revivalists, it was incorporated into what the Celtic scholar Proinsias Mac Cana has termed ‘a mythic complex’ for exploring the sacred geography of ancient Ireland and probing notions of sovereignty, the cult of the centre and the ideological unity of the whole island. Three Feis Uisnig were held consecutively between 1910 and 1912. The 1910 event was held at Togherstown House, a farmhouse bordering one side of the hill. Eoin MacNeill gave the main speech and spoke of the duty of all Irish people to speak the Irish language. The remoteness of Uisneach proved a serious setback, however. That and the decision to include a hurling competition led to the relocation of the 1911 feis to the Marist Brothers’ school in Athlone, where there were suitable playing fields. This time the gathering was addressed by the nationalist and anti-colonial historian Alice Stopford Green, who had just published her book on Irish nationality. She used the moment to speak about a deep tradition of economic industry and self-sufficiency in Ireland:

‘Fourteen hundred years ago one might have seen the Irish merchants crossing that ford of the Shannon with their little Connemara ponies, laden with shoals of fish, and bales of cloth and casks of wine to carry to the fairs of Meath along by this historic bridge, showing already that Irishmen were able to develop the industries of Ireland for the profit of Irishmen’.

Present at both feiseanna was the Belfast solicitor and Ireland’s most celebrated antiquarian Francis Joseph Bigger. He arrived in his motor car—fondly referred to in his correspondence as ‘Cuculainn’s Chariot’—accompanied by flag-bearing pipers in saffron kilts. From the effusive reports of his presence in the local press, Bigger had played a key supporting role in the organising of the Uisneach feiseanna that extended to the founding and funding of the Athlone Piper’s Club.

But the deepening Home Rule crisis brought an end to the event after the third feis in 1912. The Hill of Uisneach transitioned from a place of cultural possibility and the re-imagining of history to a location for political organisation. A Bureau of Military History statement [Michael McCoy, BMH WS 1610, p. 11] mentions that a ‘big mobilisation of Volunteers was ordered for the Hill of Uisneach’ in the second week of January 1919, days before the sitting of the first Dáil. Seán T. O’Kelly and Laurence Ginnell MP spoke. In August 1923 Helena Molony addressed an anti-Treaty rally on the hill, demanding the release of political prisoners held by the Irish Free State.

R.A.S. MACALISTER AND THE FIELD EXCAVATION

Bigger’s interest in Uisneach was no doubt a significant factor in stimulating a similar enthusiasm in two close intellectual colleagues, the archaeologist R.A.S. Macalister and the naturalist Robert Lloyd Praeger. Macalister, whose archaeological reputation was established during a decade of fieldwork excavating biblical sites in Palestine, was appointed as professor of archaeology at UCD in 1909. His hopes to undertake field excavations of Uisneach were frustrated for over a decade owing to problems in establishing the ownership of the land. Once this had been finally settled in 1925, Uisneach became the first excavation undertaken by the Irish Free State and it was supported by the Archaeological Exploration Committee of the Royal Irish Academy and the Linnaean Society. In 1928 the Academy published an impressively detailed and richly illustrated Report on the excavation of Uisneach. A main finding was an extensive bed of ash, which, they speculated, might be considered as evidence of the mystic fire that blazed for seven years and is referenced in the Dindshenchas.

There is cruel irony in the fact that the main excavation of Uisneach in 1925 coincided with the work of the Boundary Commission. That dream of unity that had driven the women and men of the Cultural Revival to locate Uisneach at the centre of their sacred landscape was extinguished by the political realities of partition. After 1928 Uisneach was erased from the national memory and its symbolic significance withdrew until it was restored by recent geophysical and palaeoenvironmental surveys and the annual Bealtaine Fire Festival.

Angus Mitchell received a Royal Irish Academy Decade of Centenaries Bursary to undertake research into the Hill of Uisneach.

Further reading

F. Armao, Uisneach or the centre of Ireland (London, 2023).

R. Illingworth, ‘Sacred Uisneach’, Irish Roots 4 (2015).

R. Schot, Ritual and royalty at Uisneach, Co. Westmeath. Archaeology Ireland Heritage Guide No. 103 (Dublin, 2023).