By Mary MacDiarmada

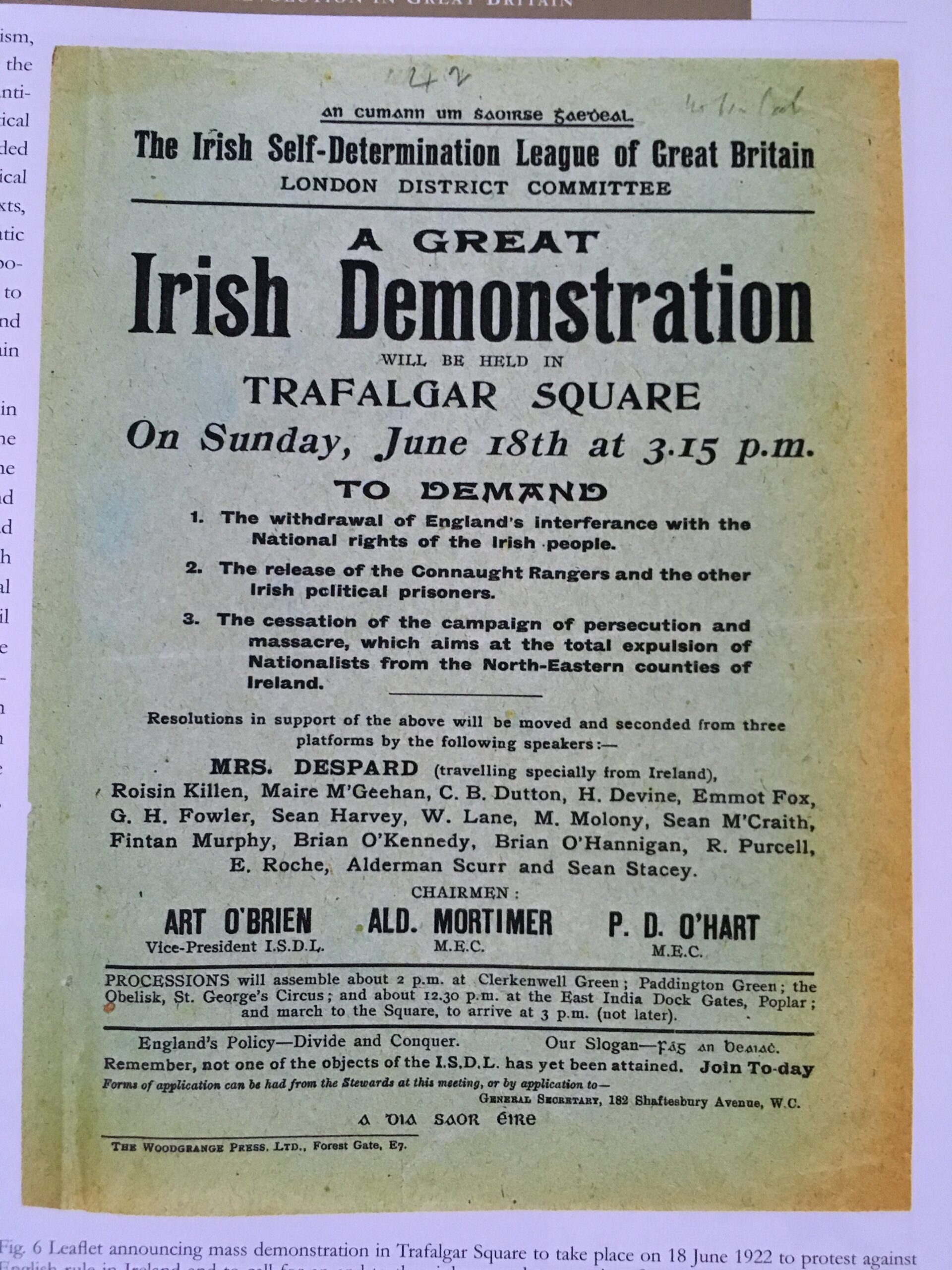

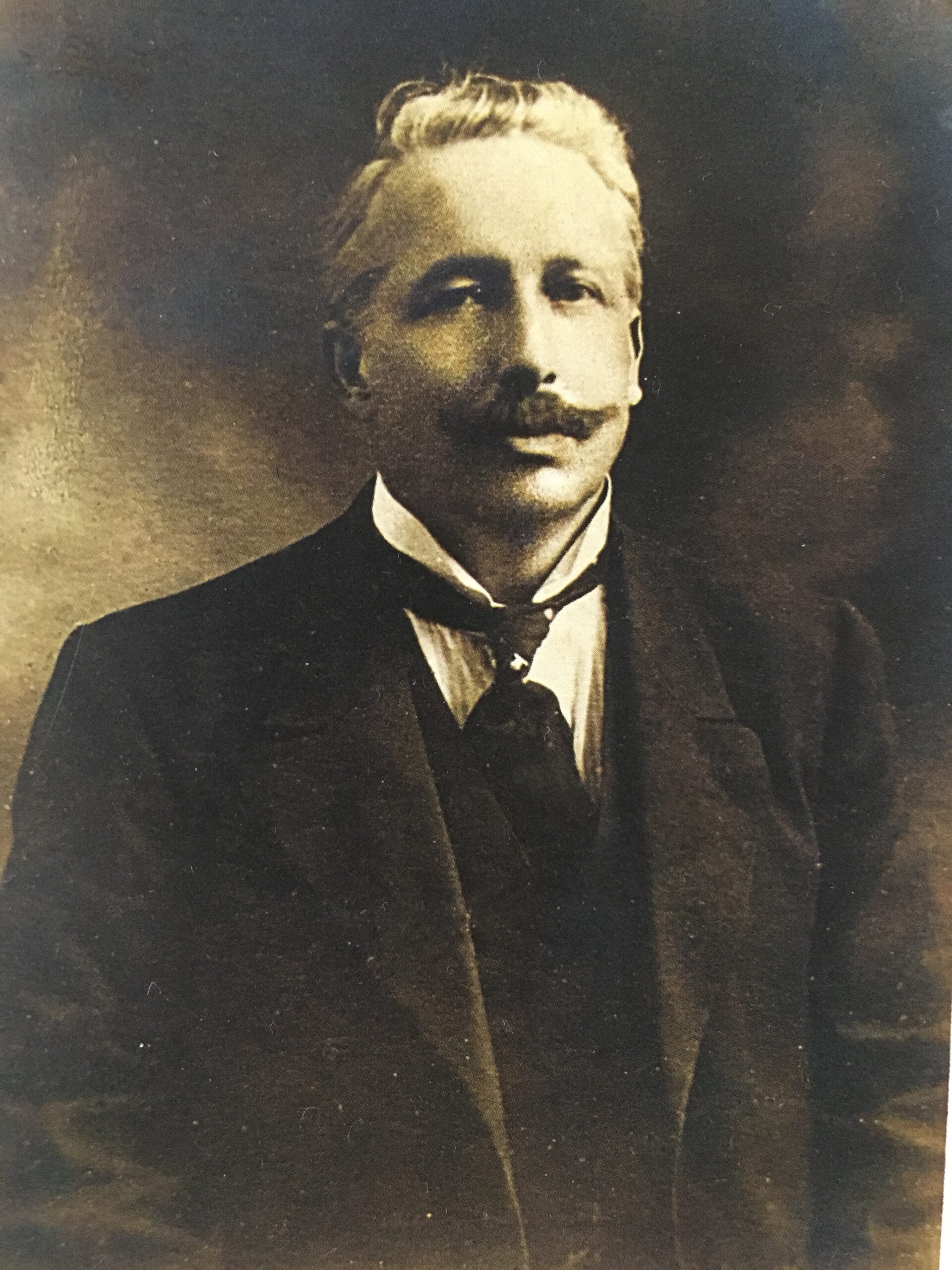

Art O’Brien was born in London in 1872. His father was from Cork city and his mother was English. O’Brien senior joined the British Army at a young age and eventually settled in London when he returned to civilian life. His father died when O’Brien was just five years old, but his mother kept in touch with her Irish in-laws and regularly brought Art on holidays to Cork. He later spoke of hearing the Irish language spoken in Cork and said that this encouraged him to join the Gaelic League in London. He moved from the Irish-language-based cultural nationalism of the Gaelic League to militant republicanism while maintaining a lucrative career as an electrical engineer. He joined the Irish Volunteers in late 1914 and this led him into organising the finance for gunrunning activities for the 1916 Rising. After the Rising he organised an extensive support system for Irish rebels who were imprisoned or interned in Britain. The impact of the execution of the leaders of 1916 also propelled him into the IRB. His significant contribution to the Irish revolutionary struggle resulted in his appointment as Dáil Éireann envoy to London in 1919, a position he embraced with verve and determination, blending support for political prisoners with the provision of ammunition for the War of Independence and an impressive propaganda campaign in favour of Irish independence. At de Valera’s request, he set up in 1919 the Irish Self-Determination League of Great Britain, which at its height numbered c. 27,000 members.

‘ENVOY OF THE IRISH REPUBLIC’

O’Brien was a key enabler in London for Michael Collins, and they corresponded on a daily basis throughout the War of Independence. O’Brien was also centrally involved in mediation between Sinn Féin and the British government in late 1920 and early 1921, and it was he who introduced de Valera to Lloyd George at their first official meeting in July 1921.

O’Brien vehemently rejected the Treaty within hours of its signing. He began fund-raising and gunrunning for the republicans immediately. On 16 April 1922 the Provisional Government terminated his position as Dáil envoy in London but he continued to regard himself as the ‘envoy of the Irish Republic’.In his new incarnation as de Valera’s man in London, he began to issue press bulletins attacking the Provisional Government and supporting the anti-Treaty position. He travelled over and back to Dublin every few weeks during the first six months of 1922. De Valera urged him to use all his press contacts for a propaganda campaign in support of the republic. In particular, O’Brien was asked to focus on the threat of war used by the British in relation to the Treaty and to state that Griffith and Collins were ‘acting dictatorially … a law unto themselves’. O’Brien made extensive arrangements to organise and fund republican envoys in Paris (Leopold Kerney), Genoa/Rome (Dónal Hales) and the US (Laurence Ginnell) during late 1922 and early 1923. In late 1922 de Valera asked him to co-ordinate a complaint to the International Red Cross about the ill-treatment and executions of republican prisoners. O’Brien was also actively involved in channelling money from the US through London to Dublin for the republicans. Nearly £8,000 was transferred, but much of it was intercepted by intelligence services in Dublin.

Correspondence between de Valera and O’Brien during this period shows that de Valera still hoped that world opinion could be swayed in favour of a republic and that he would be invited once again to meet Lloyd George. This was not as unrealistic a position as it might now seem. In September 1922 the British were concerned that there was only one signatory to the Treaty—Eamonn Duggan—who had ‘neither died nor ratted’, and Churchill had concerns at that stage that de Valera would return to his position as a political negotiator.

In spite of O’Brien’s activities,anti-Treaty IRA activity in Britain was actually at a very low level. The Irish in Britain were tired of republicanism and were turning their attention to local matters. The Home Office reported in December 1922 that ‘more than 90% of the Irish in Great Britain are in favour of the Free State … the remaining small minority are not among those who count socially, politically or in the commercial world … they are mainly young men and women led by fanatics and intriguers … the majority have neither pluck nor intelligence’.

DEPORTATIONS

In late 1922, however, the Free State government came to the conclusion that republicans in Ireland were getting ammunition from England in fairly large quantities. British government officials suggested that they could support the Free State by arresting republicans in Britain and deporting them to Dublin. In the early hours of 11 March 1923 over 100 people,including Art O’Brien,were rounded up in Britain under regulation 14B of the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act. They were taken from Liverpool to Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire) on HMS Castor. From Kingstown the group were transferred in two navy destroyers to the North Wall, and thence to Mountjoy prison in Dublin.

The Home Office was initially delighted with the effect of the deportations, believing that they had brought the anti-Treaty organisation in London to a standstill. The delight was very short-lived, however. The deportations caused a furore on both sides of the Irish Sea, with questions asked in the Dáil and in the House of Commons as to their propriety and legality. In the Dáil Thomas Johnson, leader of the Labour Party, expressed concern as to whether the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act was used in contravention of Ireland’s new status. He believed that the British government’s actions implied that it still had supreme control in Ireland,and also noted that the same government was now composed of people who would like to belittle the amount of authority that had been won by the Treaty. W.T. Cosgrave moved quickly to quell any objections, insisting that ‘we asked for those prisoners … we got those prisoners … the parties to the agreement in this case are equal’. Kevin O’Higgins insisted that ‘none of us lost a wink of sleep as to whether it was or was not a derogation of sovereignty’.

LEGAL CHALLENGES

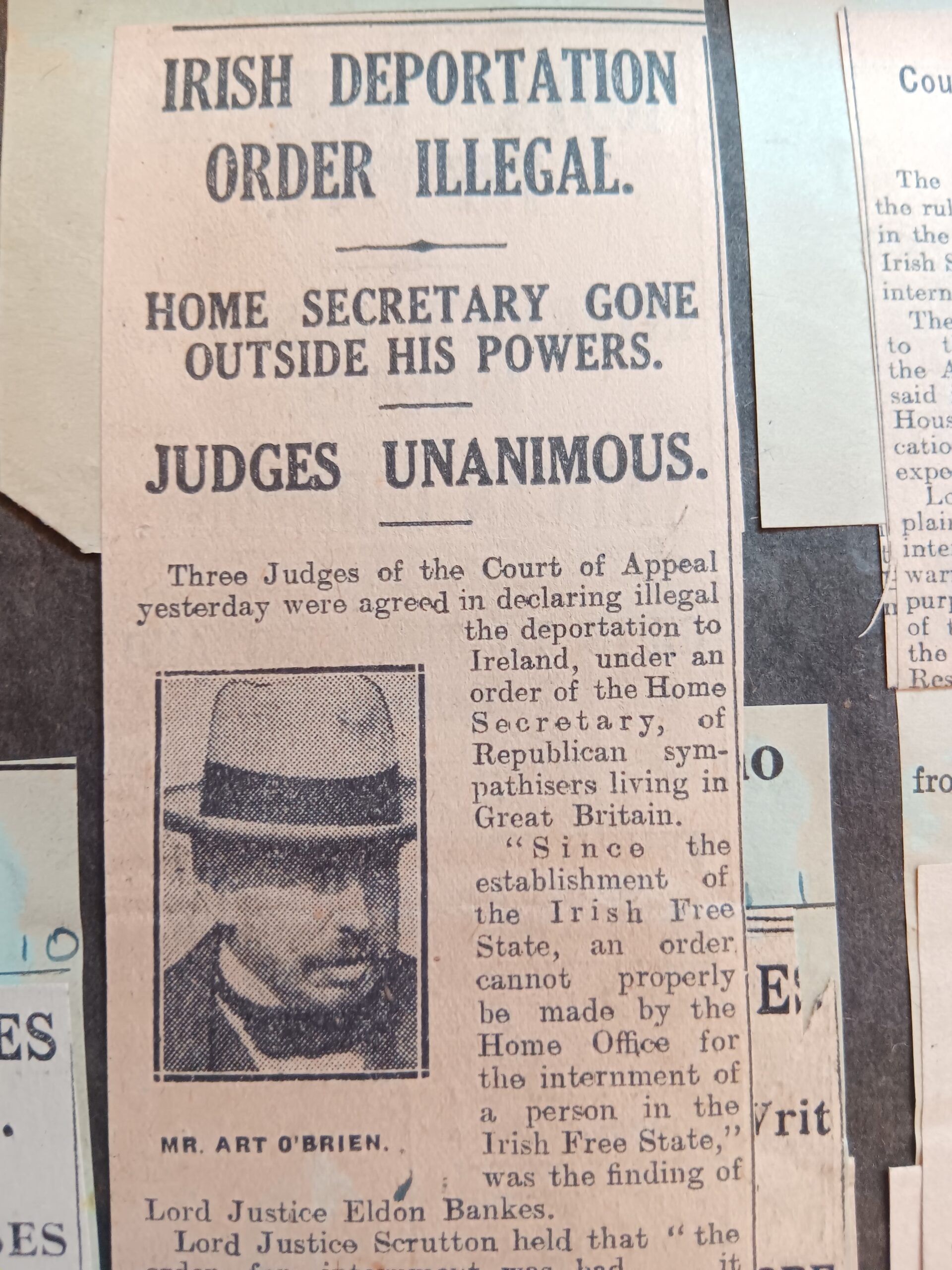

O’Brien had many friends in the House of Commons, including the Indian nationalist and also communist MP Shapurji Saklatvala and the Labour MP George Lansbury. They both leapt into action in the House, querying the legality of the deportations. Debates in the Commons kept up the pressure, and before the end of Marchthe British government established an advisory committee to which the deportees could make representation. The Free State government agreed to allow individuals to travel back to Britain for the hearings and also allowed the detainees to avail of legal advice. O’Brien was very quick to grasp this opportunity. He instructed his solicitors to make an application for a writ of habeas corpus to the divisional court in London. The Habeus Corpus Act of 1679 specifically prohibited illegal imprisonment of British subjects in prisons ‘beyond the seas’. The basis of this legal challenge was that the establishment of the Free State had abrogated the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act and that any regulations made thereunder were invalid.

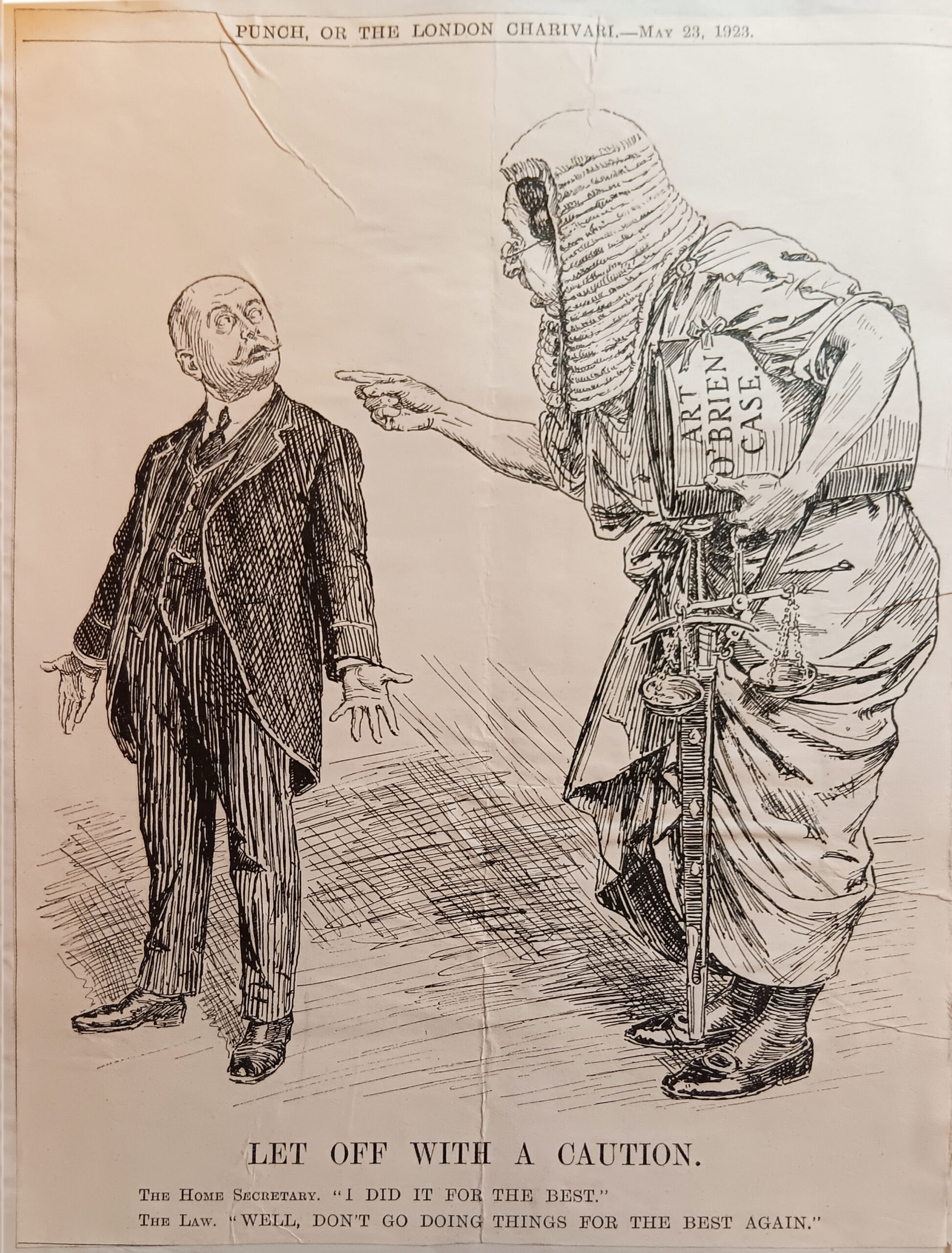

The case was heard on 10 April 1923 but was rejected. The application was renewed on 13 April before the Court of Appeal, where Patrick Hastings KC, appearing for O’Brien, invoked a statute of Charles II which declared it ‘illegal to remove the King’s lieges across the water’. The fact that O’Brien did not recognise the king was irrelevant, according to Hastings; he was still a British subject. In a unanimous decision, the Court of Appealruled that O’Brienhad been illegally deported and must be produced before the court on 16 May 1923. An appeal to the House of Lords by the British government against this decision was unsuccessful. O’Brien’s case had succeeded in making a mockery of the procedure employed by the British government. Ironically, in accepting O’Brien’s argument, the Court of Appeal cemented the status of the Free State as a separate judicial entity to the UK and as a nation state in its own right. This point was not lost on Hugh Kennedy, the Irish attorney general: ‘The judgement is of great interest to the Free State, embodying as it does the recognition by English law of the co-equality of the country with Great Britain’.

PRESS COVERAGE

Within days all of the deportees were released and escorted back to England. Considerable coverage in the press made O’Brien a household name in Britain and Ireland. According to the Daily Mail, O’Brien ‘stood debonair and smiling in court … waiting for the Attorney General to produce “the body”’. The London Times summed up the attitude of many in Britain: ‘No one outside a small group of fanatics and dreamers can have the smallest sympathy for Mr O’Brien … but the issue decided was of great constitutional importance’. The Daily News lauded the decision as ‘a warning to all future British governments of the danger of tampering with the liberty of British subjects’. O’Brien’s long-time friend Shapurji Saklatvala congratulated him in a telegram: ‘Hearty congratulations, also thanks of British citizens whom you have protected against fanciful arrest by a cabinet of incompetent lawyers and easy-going home secretary … you have also baffled plans of so-called Irish Free State whose head is like any slave-boy running after imperial chariot’.

The British cabinet met to discuss the appeal decision and decided that it was necessary to introduce a bill to indemnify the home secretary and the attorney general from civil or criminal charges in relation to the deportations. The penalties for breach of the Habeus Corpus Act of 1679 included prison for life and forfeiture of all goods and chattels. Although the indemnity bill was passed, the government endured widespread criticism and ridicule in the Commons. The O’Brien case became a cause célèbre in British legal circles and the indemnity bill was described by Lord Justice Sankey some years later as ‘an ad hoc order of council to legalise ex post facto acts which were clearly ultra vires’.

UNANTICIPATED BONUS FOR THE IRISH FREE STATE

O’Brien’s elation and his freedom were short-lived, as he and six other deportees were rearrested immediately after their release at the Old Bailey. He was convicted of seditious conspiracy and sentenced to two years in jail on 4 July 1923. The judge described O’Brien as ‘the rallying point, the central figure,the presiding genius of the whole republican movement in this country [Britain]—the alter ego of de Valera, the chief in Ireland’. He concluded that O’Brien and his co-accused were party to ‘a wicked seditious conspiracy to overthrow His Majesty’s government in Ireland’. O’Brien’s immediate rearrest negated any personal gain and put an end to republican activity in London. That the case affirmed the independent status of the Irish Free State was an unanticipated bonus for Cosgrave but highly ironic for O’Brien; he had inadvertently given a much-needed fillip to the Free State while also strengthening British civil liberty legislation.

For all the furore caused by the deportations, the actions taken had the desired effect of removing O’Brien from the republican scene in London. Tim Healy, the governor-general of the Irish Free State, personally thanked the home secretary some months later, opining that without the British action ‘The Free State was down and out’. By late 1923 the vast majority of the Irish in Britain regarded the Treaty as the settlement of the Irish question and had moved on to different concerns.

Mary MacDiarmada is a Research Fellow in the School of History and Geography at Dublin City University.

Further reading

D. Foxton, Revolutionary lawyers, Sinn Féin and Crown courts in Ireland and Britain, 1916–1923 (Dublin, 2008).

M. MacDiarmada, Art O’Brien and Irish nationalism in London, 1900–1925 (Dublin, 2020).