By Joseph E.A. Connell Jr

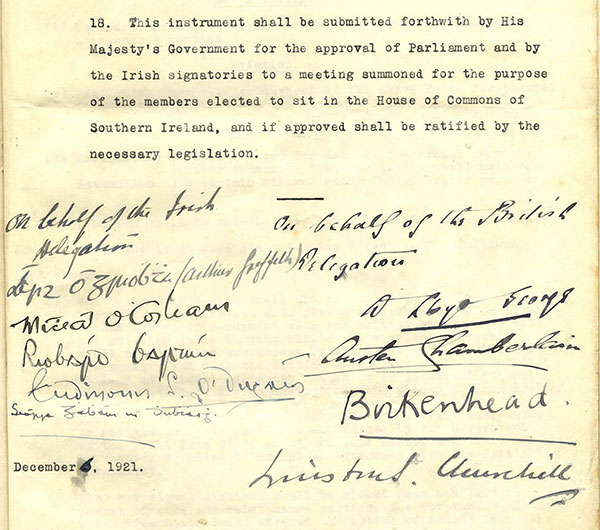

On 6 December 1921, ‘Articles of Agreement for a Treaty’ were signed in London between delegates representing Ireland and Britain. The Irish delegation had been in London since October, and in late November they returned to Dublin to consult with the cabinet according to their instructions, and again on 3 December.

When they returned to London, Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith hammered out the final details of the Treaty, which included British concessions on the wording of the oath and the defence and trade clauses, along with the addition of a boundary commission and a clause upholding Irish unity. Collins and Griffith in turn convinced the other plenipotentiaries to sign the Treaty.

Collins later claimed that at the last minute British Prime Minister David Lloyd George threatened the Irish delegates with a renewal of ‘terrible and immediate war’ if the Treaty was not signed at once. This was not mentioned as a threat in the Irish memorandum about the close of negotiations but as a personal remark made by Lloyd George to Robert Barton, and merely a reflection of the reality of any military truce.

The delegates returned to Dublin and two days later the cabinet met. Cathal Brugha, Eamon de Valera and Austin Stack voted against the Treaty; W.T. Cosgrave and those who had been plenipotentiaries—Robert Barton (reluctantly), Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith and George Gavan Duffy—voted for it. (The fifth plenipotentiary, Edmund J. Duggan, was not a member of the cabinet.) De Valera denounced the delegates for their breach of faith in failing to consult him before signing, but Barton countered by insisting that the real problem had been caused by de Valera’s refusal to attend the conference. Later, de Valera told the Dáil: ‘now I would like everybody clearly to understand that the plenipotentiaries went over to negotiate a Treaty, that they could differ from the Cabinet if they wanted to, and that in anything of consequence they could take their decision against the decision of the Cabinet’.

Though all discussion in the Dáil, the newspapers and most books refer to a ‘treaty’, the British and Irish delegates did not sign a treaty. They signed a document entitled ‘Articles for Agreement’. The words ‘for a Treaty’ were added to the British copy, but by that time the Irish copy was being delivered to Ireland.

That evening de Valera issued a press statement that he called a ‘Proclamation to the Irish People’, indicating that he could not recommend acceptance of the Treaty:

‘The terms of this agreement are in violent conflict with the wishes of the majority of this nation, as expressed freely in successive elections during the past three years. I feel it my duty to inform you immediately that I cannot recommend the acceptance of this treaty either to Dáil Éireann or to the country. In this attitude I am supported by the Ministers for Home Affairs and Defence. The greatest test of our people has come. Let us face it worthily without bitterness, and above all, without recrimination. There is a definite constitutional way of resolving our political differences—let us not depart from it, and let the conduct of the Cabinet in this matter be an example to the whole nation.’

On 14 December 1921 the Dáil assembled but there was no debate on the Treaty itself, just a discussion on the actions of the plenipotentiaries in signing the Treaty without ‘permission’ from the cabinet.

Both the Dáil and the British Parliament had to ratify the Articles before they could take effect. The British wasted no time in having the Articles approved by both the House of Commons and the House of Lords; they received the royal assent on 31 March 1922.

Joseph E.A. Connell is the author of The terror war: the uncomfortable realities of the Irish War of Independence (Eastwood Books).