By Keith Jeffrey

IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM)

It might be argued that the most significant thing about the Irish cultural response to the First World War is its comparative absence. Perhaps it is a case of ‘the dog that didn’t bark’, itself a noteworthy enough reaction to the cataclysmic European events of 1914-18.

There is, for example, no extensive body of Irish war poetry, although war or war-related poems were produced by a number of Irish writers, including W. B. Yeats, Tom Kettle, Katherine Tynan and Francis Ledwidge. On the other hand, there is quite a large body of prose, both novels and non-fiction, which can help illuminate the specific impact of the war on Ireland and Irish society. There is, too, some important relevant evidence in the visual arts.

Theme of detachment

A theme which emerges from Irish writing about the war is one of distance, disengagement or detachment from the conflict, exemplified above all by perhaps the most famous Irish Great War poem: Yeats’ ‘An Irish airman foresees his death’. The aviator makes his political position abundantly clear: ‘Those that I fight I do not hate,/Those that I guard I do not love.’ The pilot did not enlist from any patriotic or ethical motive: ‘Not law, not duty bade me fight,/Nor public men, nor cheering crowds./A lonely impulse of delight/ Drove to this tumult in the clouds.’ There is here an element of the old ‘fighting Irish’ stereotype, if in a rather refined form. As such, the poem is patronising and even insulting to Irish intelligence, for there is surely nothing quite so stupid as fighting for its own sake – behaviour which contributes to that other pernicious Irish stereotype: the ‘thick Paddy’.

The theme of detachment recurs in some of the visual representations of the war by the Irish painters William Orpen and John Lavery, both of whom were living in England at the time of the war. In the early spring of 1916 Orpen’s pupil and studio assistant Sean Keating, a noted artist in his own right, hac! to leave London and return to Ireland in order to avoid conscription (Michael Collins left England at the same time for the same reason). Keating tried to persuade Orpen to accompany him: ‘Come back with me to Ireland. This war may never end. All that we know of civilisation is done for … I am going to Aran …. Leave all this. You don’t believe in it.’ But Orpen remained in London, claiming that everything he had he owed to England. ‘This is their war’, he said, . ‘and I have enlisted. I won’t fight, but I’ll do what I can.’ Orpen went to France to paint Dead Germans in a Trench, among other pictures, while Keating went to Aran to paint Men of the West, and later Men of the South (themselves ‘war’ paintings of a sort).

William Orpen

Although Orpen never properly returned to Ireland after August 1915 (a one-day visit in 1918 was the only time he returned home again before his death in 1931), he never lost his Irishness, at least in others’ perception of him. Despite his unassailable position as the court painter to the British establishment, and as an official War Artist employed by the British Ministry of Information, he remained an outsider looking in. On the western front, he was An Onlooker in France, the title he took for his illustrated war diary which was published in 1921.

There are two principal features about Orpen the Irishman and war artist. First was his detachment from the actual conflict, stemming from both his status as an official observer of the war (in which capacity he was not permitted to go up to the front Final version. (COURTESY OF THE IMPERIAL WAR MUSEUM) line), and also as an Irishman, not wholly engaged in what we might call the Anglo-German conflict. This detachment, however, was coupled with an intense sympathy for the common soldier. In the preface to An Onlooker in France, Orpen noted his ‘sincere thanks for the wonderful opportunity that was given me to look on and see the fighting man, and to learn to revere and worship him’.

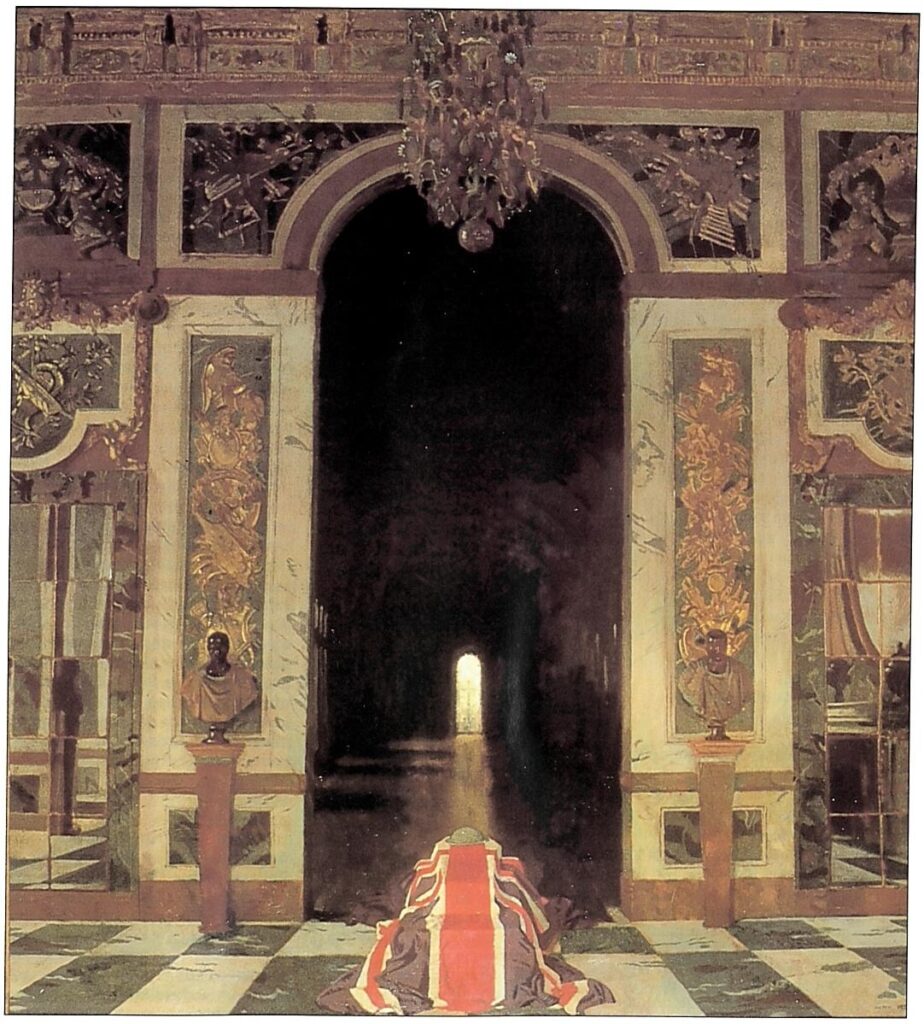

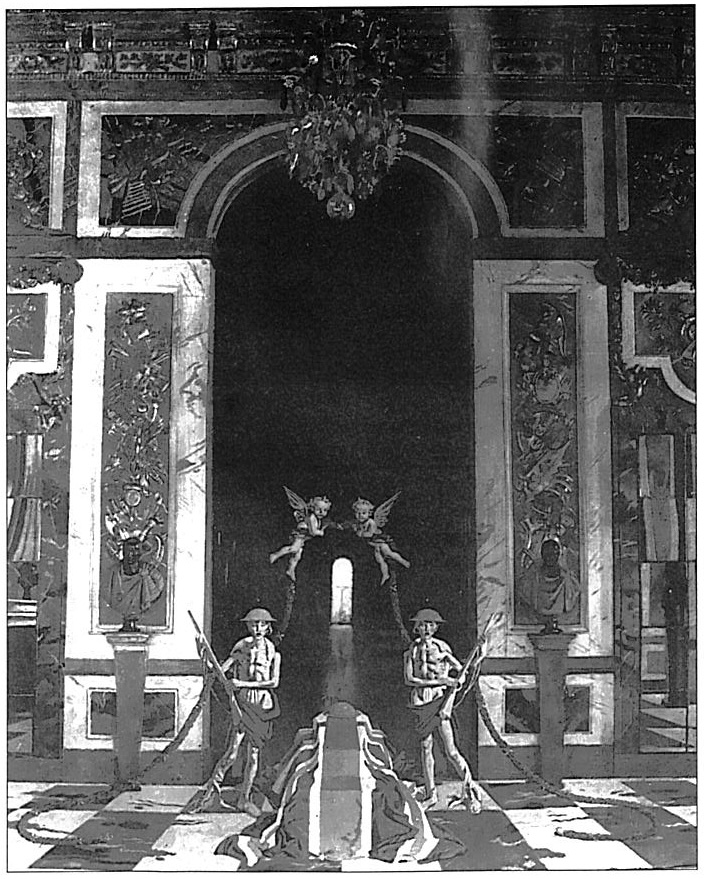

We can see this illustrated most vividly in the third of his three great peace paintings, which the Imperial War Museum in London commissioned him to produce in 1919 for a total fee of £6,000. In the first two, A Peace Conference at the Quai d’Orsay and The Signing of Peace in the Hall of Mirrors, Versailles, 28th June 1919, the statesmen are dwarfed by the overwhelming size of the state rooms they occupy. There is not much sympathy in Orpen’s compositions for the important individuals depicted: President Wilson, Clemenceau, Lloyd George and so on. But the third painting, To the Unknown Soldier in France, is rather different. It was originally intended to show some forty ‘politicians and generals and admirals who had won the war’, and Orpen conceived a similarly monumental setting in the ‘Hall of Peace’ on the way in to the Hall of Mirrors. But he abandoned this plan – ‘And then,you know,’ he later told the London Evening Standard, ‘I couldn’t go on. It all seemed so unimportant somehow beside the reality as I had seen it and felt it when I was working with the armies. In spite of all these eminent men; I kept thinking of the soldiers who remain in France for ever …. So I painted all the statesmen and commanders out.’

Gilded pomp contrasted

with ragged misery Orpen then painted a single coffin shrouded in an Union Flag, and placed ghostly semi-naked British soldiers on each side, rather like armorial supporters, the whole completed with two cherubs floating above holding green and gold garlands. The figures of the soldiers, in fact, were drawn from Orpen’s actual experience. They were based on a painting called Blown Up – Mad which Orpen said was ‘an actual portrait study of a man I met behind the lines in France. This soldier had been blown up by a mine. Practically every shred of uniform had been torn from his body. He was wandering crazed and naked, still clinging to his rifle.’ The gilded pomp of the Palace of Versailles .. .’, went one interpretation, ‘is imaginatively contrasted with the ragged misery of the ghostly boy-soldiers who watch over the coffin of their comrade. Festooned Cupids and the Cross shining in the distance are symbols of the ‘Greater Love’ of those who have laid down their lives.’ The picture reflected Orpen’s own view that the only tangible result of the war had been ‘the ragged unemployed soldier and the Dead’.

Unseemly dispute

Many critics did not like the painting, although the public did, voting it ‘Picture of the Year’ at the Royal Academy’s 1923 summer exhibition. The Imperial War Museum refused to accept it, which incidentally led to an unseemly dispute over the unpaid balance of the artist’s fee. Opinions tended to divide on political lines. The left-wing Daily Herald welcomed it as ‘a magnificent allegorical tribute to the men who really won the war’. The Liberal Liverpool Post responded equally sympathetically. Sir William Orpen, it reported, had declined ‘to paint the floors of hell with the colours of paradise, [or] to pander to the pompous heroics of the red tab brigade. The Imperial War Museum may reject the picture, but the shadow legions of the dead sleeping out and far will applaud it with Homeric hush’. By contrast the right-wing Patriot, taking the opportunity to criticise John Lavery for his public sympathy with Irish nationalism, disagreed and called it ‘a joke – and a bad joke at that. Sir William Orpen, by the way, is an Irishman, like his brother artist Sir John Lavery’.

The English people are very patient and very indulgent. But perhaps they are not quite so stupid as some of the Irish who live amongst us suppose. When an Irishman who accepts the hospitality of this country and profits by its wealth and its culture espouses the cause of Sinn Fein like Sir John Lavery, or takes liberties with our feelings of reverence like Sir William Orpen, there is an obvious comment which rises to the lips, but is not usually uttered. If these are their feelings, why do they not go and live in their own country? Certainly to artists who have a turn for the grotesque and the fantastic desolation of war, there are excellent subjects ready to hand in Southern Ireland.

Five years later Orpen offered to paint out the soldiers, cherubs and garlands and dedicate the picture as a memorial to Earl Haig, an ironic conclusion in view of Haig’s subsequently tarnished reputation as an outstanding British general. Having done thiS, the Museum finally accepted the painting.

Orpen thus shifted from the second characteristic of his war art – his human – humane – sympathy, albeit expressed in a strikingly (though not for him uncharacteristically) surreal fashion – back to a more detached and abstracted memory. The people are literally painted out. The history of this painting – itself a war memorial – precisely reflects a central choice faced by those commissioning the more familiar type of public war memorial. Do you chose for your design some figurative representation – a soldier (usually), civilian or symbolic figure expressing victory, mourning, or whatever? Or do you opt for an abstract structure, such as a column, obelisk, cross, or most famous of all, a cenotaph?

John Lavery

The second notable Irish painter of 1914-18, also an official War Artist, was the Belfast-born John Lavery. Although, like Orpen, he was an immensely successful portrait painter, his war paintings contain little of the strong human emotion displayed by his Dublin-born compatriot. Most of his pictures depict the home front, principally in a conventional landscape mode. Painting warships far from the fighting, at Scapa Flow, Lavery conceded that he ‘felt nothing of the stark reality, losing sight of my fellow men being blown to pieces in submarines or slowly choking to death in mud. I saw only new beauties of colour and design as seen from above.’ A similar pleasure with shape and form can be seen in his paintings of British airships, but they are not pictures of much passion, and Lavery himself afterwards dismissed his war paintings as ‘dull as ditchwater’.

William Conor

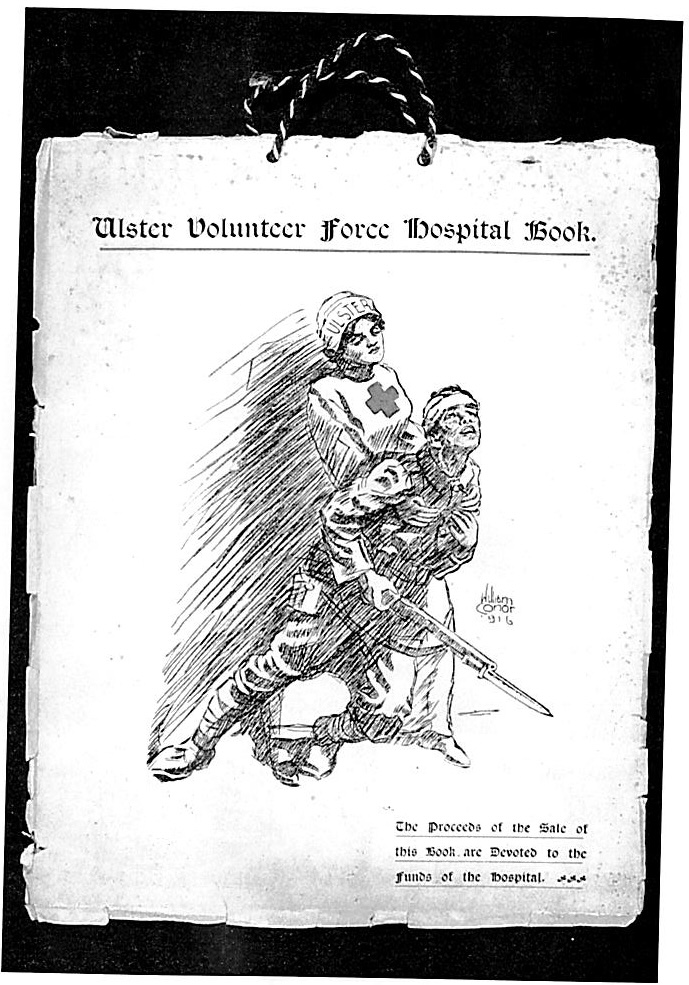

Images of the Great War were also being produced by William Conor in Belfast. Of the three artists he was certainly closest to ‘the people’. His vigorous and personable, if rather folksy, sketches of soldiers in the 36th (Ulster) Division were effectively uniformed versions of the tinkers and shipyard workers for which he subsequently became known. In so far as Ulster aspired to the ideal of ‘a nation in arms’ (if ‘nation’ it was), this was it. His pictures mostly dealt with the home front or soldiers training before they went overseas. They also record the role of women in the war effort, and included a commissioned painting of a female munitions worker at Mackies (the Belfast engineering works) and one of a nurse supporting (rather uncomfortably) a wounded soldier, which was used for an Ulster Volunteer Force Hospital fund-raising brochure. Reflecting a more conventional view of war service, however, in 1919 he exhibited a painting entitled The Glorious Dead.

Availability in Ireland

What was seen of this war art in Ireland? The answer is not much. Conor exhibited several war-related works at the Belfast Art Society between 1914 and 1919, several of which were bought by the Belfast Municipal Art Gallery, but none of Orpen’s war paintings ever came to Ireland. In May 1918 he had a major show of 125 works at Agnew’s gallery in London. The Board of the National Gallery of Ireland was ‘very anxious’ to have it. ‘Irishmen’, wrote the gallery director, Langton Douglas, ‘are proud of Sir William Orpen and his pictures would help to lift some of them out of their parochialism’. But in the end both the costs of bringing the pictures to Dublin, which the National Gallery was unable to meet, and, possibly, the political situation, with the threat of conscription exciting political passions in Ireland, combined to deny Irish people in Ireland a sight of the war art of the greatest Irish painter of the day. The works instead went to America. The one main gap, indeed, in the National Gallery’S Orpen collection remains his war art, among which are some of his very greatest works. Although the great bulk of Orpen’s war paintings never came on the open market – as officially- commissioned works they passed to the Imperial War Museum where they remain to this day – those that have become available have never apparently attracted the National Gallery of Ireland. Perhaps it became politically incorrect for the national collection of independent Ireland to seek to purchase work, however distinguished, by an Irish artist specifically employed by the British government and serving (even as a non-combatant) in the British army.

As for Lavery, most of his war paintings also remain in the Imperial War Museum. In 1929, however, he gave a very substantial collection of works to the Belfast Museum and Art Gallery (now the Ulster Museum) among which is a large picture entitled Daylight raid from my studio window, 7 July 1917 (Front cover). It shows an aerial bombing raid on London and we see the artist’s wife looking on from within the studio. This is the only significant Great War painting in a public collection in Ireland and it provides a strikingly civilian and detached image of the war, which is reduced to a distant pattern of aircraft in conflict. This distant ‘tumult in the clouds’ is the visual equivalent of Yeats’ poem.

The cultural legacy of the Great War

The way in which the Great War was – and is – remembered and commemorated in Ireland and by Irish people exemplifies the often equivocal response, north and south, to the issues of patriotism, national sacrifice and personal loss which were raised during 1914-18 and in the following two decades .. The comparatively limited cultural legacy, in terms of music, visual art and literature, clearly reflects the lack of any coherent or whole-hearted Irish commitment to the war, or, indeed, against it. In a sense, the war did not matter to Ireland. Despite efforts to equate Ireland with Belgium, and John Redmond’s attempts to fire Irish patriotism in support of the Allied war effort, during the war itself and after there was a collective and increasing lack of engagement with the conflict. Although a great number of Irishmen volunteered to fight, and very many died, Ireland as a whole – or at least nationalist Ireland – progressively became detached from the war, becoming, like Orpen and Lavery, and Yeats’s airman, in a sense ‘onlookers’.

Keith Jeffrey is a senior lecturer in history at the University of ulster at Jordanstown.

Further reading:

K. Jeffery, ‘The Great War in Modern Irish Memory’ in T.G. Fraser and K. Jeffery (eds.), Men, Women and War. (Dublin 1993)

B. Arnold, Orpen: Mirror to an Age (London 1981)

M. and S. Harries, The War Artists (London 1983)