by Ann McVeigh

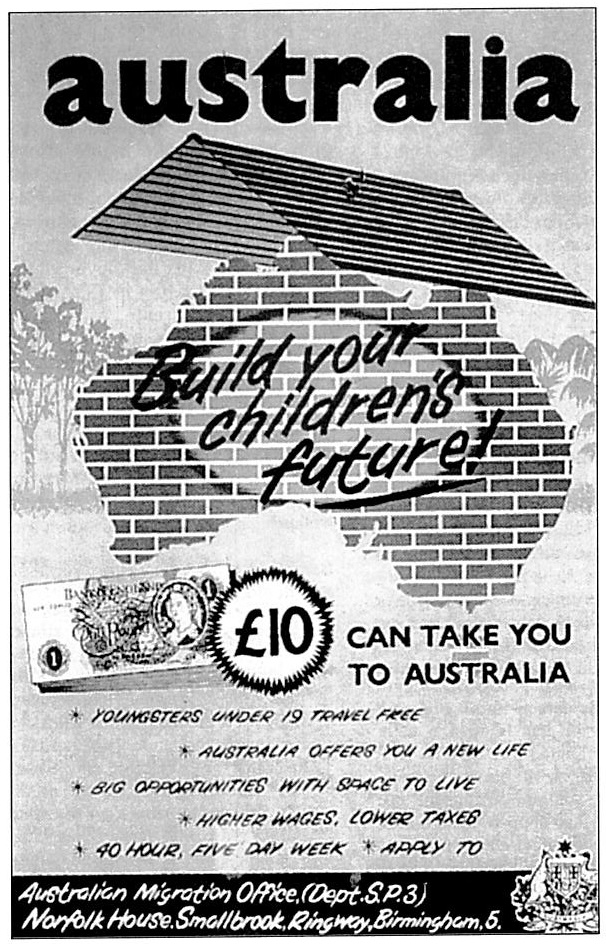

From 31 March 1947 the bargain of a life-time became available to British subjects: they could now emigrate to Australia for just ten pounds — about the equivalent of an adult male’s weekly wage.

This exceptional offer became possible after an agreement between the governments of Australia and the United Kingdom resulted in the Assisted Passage Scheme. Almost one miIlion people took advantage of the cheaprate passage to start a new life Down Under. During the period covered by the scheme (1947-71) 991 ,431 British subjects received an assisted passage. An annual average of almost 3,000 came from Northern Ireland. In the peak year of 1953, 6,300 people left to try their luck in Australia. In 1954 a record 1,548 returned (the annual average was just less than a thousand). Most people remained in Australia for more than five years.

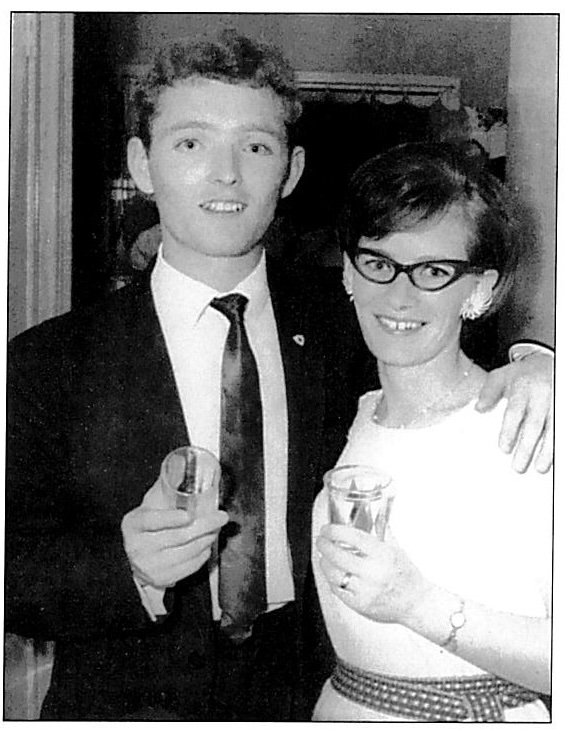

Joe and Paulette

Two people who typify those who left these shores during this period are Joe and Paulette. Their story could, simply by changing the names, be the story of any number of young emigrants from Northern Ireland. In 1966 they were a young courting couple; he was from Coalisland, she from Cookstown. In that year Joe’s uncle Frank, who had emigrated from County Tyrone to Australia in 1950, came home for a holiday. He spoke warmly of his adopted homeland and appeared to be doing very well for himself. This inspired the young couple: they were already thinking of getting married and what better way to start a new life together than by going to a new country? As Joe said; ‘I felt the urge to branch out and see something of the world while stiII young’. Paulette too wanted ‘to see more of the world’.

Unfortunately for them their wanderlust was curtailed by lack of money. Although Paulette worked as a clerk in the civil service and Joe was employed as a joiner, they did not earn enough to enable them to re-settle overseas without some financial help from a friendly government agency. ‘Money was very much in short supply, so we would not have considered emigrating without an assisted passage’, Joe recalls.

Injections

Getting an assisted passage, however, was not just a matter of asking nicely. First they had to send to Australia House in Belfast for an application form, fiII it in and send it back, then wait to see if they would be granted an interview (not all applicants were). Joe and Paulette were lucky: they were interviewed by a gentleman who came from Australia House in London and approved their application — subject, of course, to certain stipulations. They both had to pass a rigorous physical examination and submit to blood tests and X-rays. They also had to complete an immunisation programme and were given inoculations against cholera, typhoid and smallpox – a ‘sore point’ which almost made them change their minds about going! A less painful requirement was a reference from a ‘respectable’ member of the community, for example, a doctor, a JP, a minister of religion or an employer.

At the interview, and subject to acceptance, Joe and Paulette had been offered a choice in their mode of travel. Initially, they chose to sail, but after the disadvantages were pOinted out to them in terms of the time it would take (five weeks) and what that would mean in loss of income, plus the amount of spending money required on a five week voyage, they changed their minds and opted for the Qantas flight from Heathrow. Incidentally, the ‘Australia for Ten Pounds’ offer applied only from point of departure in Britain: the fare from Co. Tyrone to London they had to find for themselves.

Joe and Paulette left Ireland on Easter Monday 1967, flying from Aldergrove Airport, Belfast, to catch a connecting flight to Australia. The journey from Heathrow to Brisbane took thirtyhours altogether, with five stopovers of an hour each. The plane touched down in Athens, Tehran, New Delhi, Hong-Kong and Manila. Not surprisingly, Joe remembers being ‘completely shattered’ after the long flight, while Paulette claims she was so excited she did not sleep at all. She also remembers being served meals and snacks every two and a half hours ‘some of which were foreign to our uneducated palates’.

The Good Neighbour Council

They arrived in Brisbane at the ungodly hour of 6.15 in the morning. Even so, Uncle Frank was there to meet them. So too was a lady from the Good Neighbour Council. This good lady, whose name neither Joe nor Paulette can recall, was employed by the Australian immigration authorities, under whose aegis the Good Neighbour Council operated. The function of the council and its employees was to meet all immigrants at the various points of entry into the country and help smooth over any difficulties. If the newcommers had no immdediate accomodation there were places available for them to stay in, short-term, until they were established. Luckily Joes and Paulette had no need of this service as Uncle Frank had arranged accommodation for them at the Kedren Park Hotel, where his friend, John Nolan, was manager.

Paulette remembers feeling ‘tired and confused and overawed at first’, while Joe admitted to ‘a feeling of apprehension at the sudden realisation that our new life had begun’. These feeling were mitigated somewhat by the warmth and sunshine which gave them hope for the future. And Paulette recalls the relief she felt when she saw a familiar item – a bottle of HP sauce! Even so, settling in to life Down Under was not always easy. The newlyweds missed their families and friends. Joe particularly missed the Silver Band he had been a member of back home, while Paulette mourned for the old piano she had had to leave behind! Choosing what to leave and what to take was dictated to a large degree by the restrictions imposed by air travel: sixtY-Six pounds was the maximum weight allowed each passenger.

Getting a job

Certain things, however, were considered a necessity and so Joe had his joinery tools shipped out to him. While waiting for them to arrive he looked round for other work – and was not long in finding it. ‘The classified employment ads in the papers were full of job opportunities in those days.’ His first job was as a storeman/ packer in a warehouse in Brisbane. This warehouse serviced the retail outlets of a nationwide chain store in the Queensland area and in parts of New South Wales. Joe found it an interesting job but poorly paid and so looked for other work. He was next employed by a firm making transport buses:

This company, at the time, won a huge contract to manufacture a complete fleet of buses, to replace the old electric tram system. This change-over was to be completed in a short time and subsequently the company were taking on all trades to meet the demand. I believe they advertised in the British press, and I was told that the Belfast Telegraph carried one of these adverts.

Joe enjoyed working for this company but finally returned to his own trade, working for a company called O’Neill Industries, where, he claims, he felt a kind of kinship ‘hailing, as I do, from the O’Neill county!’ It was during this period that Joe and Paulette began to acquire the kind of lifestyle that had encouraged them to migrate in the first place. Joe’s job involved quite a bit of travelling, including a seven-month stay in the Solomon Islands: ‘Looking back, I have to say it was an exciting time in my life, and very educational.’

Mandatory two-year-stay

Meanwhile Paulette too was keeping busy. She worked part-time in a picture-framing and art reproduction shop in the centre of Brisbane: ‘Part-time jobs were plentiful in those days.’ Before long, however, Paulette quit her part-time job to become a full-time mother. Although everything was working out well for Joe and Paulette, it was not until the mandatory two-year-stay period was passed that they really settled down. If they had left Australia within two years of arriving there then under the Assisted Passage Agreement they would have had to repay the full cost of the fare to Australia (minus the ten pounds) to the Australian Emigration Scheme. According to Paulette:

I really felt at home when I got to know shopkeepers, regulars at Church, the baby clinic nurses and preschool mothers, and Joe’s football friends and their wives and, most important of all, when we knew we had the return fare home in the bank!

The pull of home

It gave them a feeling of security to know that they could go home if they wanted to, at any time. Even after two years in Australia Joe and Paulette still thought of Ireland as ‘home’ and the pull of home was strong:

When our first-born was almost ready to begin school it became increasingly obvious that we had to face a difficult decision: whether to return home (temporary or permanently) or to finally sink roots. Our decision was to return home, and we arrived back on Sunday 2 September 1972, after five and a half lucky and memorable years in Brisbane.

It was the thought of missing out on family occasions that finally influenced Joe and Paulette’s decision. Joe was the second eldest in a family of nine children and he felt he was losing a lot in not being there for their weddings and birthdays. Nor did he like the idea of his own children growing up knowing of their grandparents only through photographs and letters. Paulette had similar misgivings. Had other members of their family decided to join them in Australia it is unlikely that Joe and Paulette would have returned to Ireland.

Likes and dislikes

When asked what they liked and disliked most about Australia, Joe and Paulette answered almost in unison: the climate was wonderful as were the many outdoor pursuits designed to take advantage of it. As Paulette pointed out:

I loved the climate in Brisbane. Our whole lifestyle was determined by it – barbecues, football, outdoor pool. You woke each morning to sunshine and Kookaburras ‘laughing’. I also loved the idea that everything was geared for families – even football – it was all a family outing so you did not have the old Irish way of men in the pubs, women at the bingo or left at home knitting.

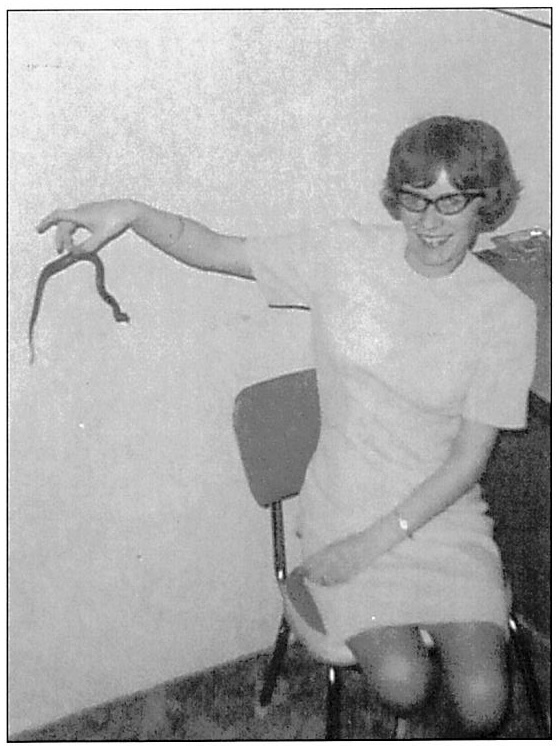

What they did not like so much was the native wildlife. Paulette had a decided and healthy dislike of snakes, black-widow spiders and the flying cockroaches while Joe discovered discovered that, although the mosquitoes in the Brisbane area were not malaria-carriers, their bite could be very unpleasant, especially if one was allergic to them – as Joe was! Unfortunately, those ‘pesky mossies’ were uninvited guests at every barbie. Despite the native wild-life, Joe and Paulette have fond memories of their time in Australia. They made many new friends among the Australians, especially ‘when they found out we were Irish’ (and not English). Joe would like to return for an extended holiday to renew these old friendships although he no longer feels that he would like to live there permanently. Paulette feels the same:

But I did consider returning to Australia in the first four or five years after we came back. I found it harder to adapt back to Irish life than I did to adapt to an Australian way of life.

Worth every penny !

Although they are now happily settled back in the O’Neill County, Paulette and Joe are very glad that they did spend time in Australia. In their opinion the Assisted Passage Scheme which allowed them the chance to travel to ‘see something of the world’ and to experience a new culture was the bargain of a lifetime. Advertised as Australia for Ten Pounds!, it was, they claim, ‘Worth every penny!’

Ann McVeigh is a postgraduate student in the Department of Social and Economic History at Queen’s University, Belfast.

In November 1948 the government of Australia signed a separate agreement with the Republic of Ireland which had recently left the British Commonwealth. This limited maximum financial assistance to £30 towards an adult fare, with lesser amounts for children according to age. The £10 cheap-rate fare did not apply.