‘Who ever met a cheerful Socialist?’

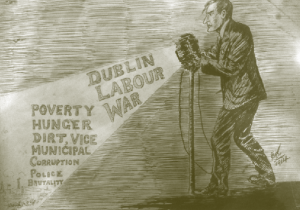

The threat of ‘ungodly’ socialist doctrine ‘infiltrating’ and ‘corrupting’ Irish workers was a very real fear amongst many social, religious and political commentators in 1913. The Catholic Bulletin warned that should ‘the poison plant of Socialism ever take root here, all that is beautiful in the Irish national character must wither’, while it asked the question ‘who ever met a cheerful Socialist?’ The Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) was perceived by many nationalist newspapers as an organisation that harboured criminals. The Meath Chronicle noted that those who joined the ITGWU were nothing more than ‘a band of highwaymen’ who ‘sheltered’ their ‘insolence’, ‘disobedience’ and ‘laziness’ under its banner. The Irish Catholic thought that ‘these bad, sad specimens of the human race have no interest in the cause of labour . . . they are not on strike, nor have they been locked out’. The Midland Reporter (Mullingar) wrote that ‘the roughs of the Dublin slums’ were prone ‘to rioting, stealing, and breaking shop windows to loot’. The Irish Times agreed, claiming that the ITGWU exercised ‘tyranny over the working classes’ and was ‘an agency whose interest is agitation rather than settlement’.

Dublin employers universally portrayed Larkin’s leadership as the ultimate cause of violent unrest in the capital and they rallied against his methods and teachings. William Martin Murphy sought to ‘kill Larkinism and what it stands for—Socialism and Anarchy’. Dublin employer Ernest Shackleton commented: ‘If Larkin took a single ticket to Buenos Ayres or Hong Kong we would not object to our men belonging to the Transport Union. What we object to is Larkinism, not legitimate trade unionism.’ Larkin’s brand of trade unionism was declared by the Connacht Tribune (Galway) to be ‘not the unionism practised in sober England’; instead, it ‘preached false and dangerous doctrines’. Nationalist councillor C.F. McNally told Carlow District Council that it was the use of ‘the sympathetic strike’ that was ‘destructive to all progress’ in resolving the dispute in Dublin, ‘a flame fanned by Socialistic and Communist interests foreign to our common country’.

High levels of unemployment and the prevalence of casual employment with low wages, together with the plight of tens of thousands of labourers barely existing in slum conditions, served to heighten the atmosphere of bitterness and discontent in the winter of 1913. Arnold Wright, who provided the employers’ viewpoint on the dispute in Disturbed Dublin, was forced to concede that Dublin’s inner city was ‘a maze of streets physically and morally foul’.

Idealised view of country life

Public commentators across nationalist Ireland often juxtaposed the unsanitary conditions and perceived moral degeneracy of life in Dublin city with a romanticised view of country living. The Catholic Bulletin noted in October 1913 that ‘young men and women are too easily lured from saintly country homes to aggravate Dublin’s complicated labour problem’ and ‘they often fall prey to the vices of city life’. The Lockout served to focus attention on similar slum conditions in other parts of the country, and The Derry Weekly News and Tyrone Herald noted:

‘The tenement houses in the towns are the analogue of the congested districts in the country. In such places human life festers and decays . . . Men are turned into beasts . . . In every urban slum, in every rural slum, in every poisonous and insanitary house, the divine laws and the natural laws are broken . . . It has made the publican and gombeen man and the owner of the slum property the rulers in our towns and made them the meanest and least ideal congregations of human life one could find anywhere.’

The Times in London claimed that nationalist politicians had always remained ‘studiously silent’ on the issues of poverty and neglect, claiming that ‘ardent members of parliament are always streaming through Dublin, but they have never found time or inclination to expose such grievances’. The editor reproached ‘the Churches, the employers of labour, the public men and the wealthy private folk, none can escape their share of blame’. It proclaimed that ‘Dublin ought to be one of the healthiest cities in the world. It is swept by life-giving sea breezes. Yet people die like flies in its squalid slums, while even the broad expanse of the Phoenix Park remains for the most part deserted and desolate.’

Irish Party MPs were indeed reluctant to proactively address the escalating violence and suffering during the dispute despite the apparent misgivings of a small number of party members. Following the violence of Bloody Sunday in late August 1913, Richard McGhee, MP for mid-Tyrone, wrote to John Dillon to express his concern that the party had not yet condemned the attacks: ‘I had expected to see a letter from you in the Freeman today denouncing the murderous attack upon peaceful citizens on Sunday last. It will be a serious mistake for our entire Irish Party to remain silent as if we approved of the devilish work.’ McGhee noted that this would appear even more serious considering that ‘the trade unions of Britain are stirred to the deepest indignation’ over the attacks. Instead, Dillon fantasised about how both sides annihilating each other might end the entire dispute and thereby solve the problem. In early October he told his close friend T.P. O’Connor, Irish Party MP for Liverpool, ‘it would be a blessing to Ireland’ if both Murphy and Larkin ‘exterminated each other’.

Many nationalist MPs were actively hostile to the strikers, and David Sheehy’s attempt to portray the workers as merely the dupes of Larkin was typical of the inherent disinterest in the workers’ genuine grievances amongst respectable nationalists. Sheehy declared that ‘there were a great many fine decent good men in Dublin out of employment, commanded out of employment by Mr Larkin, under the feeling, under the threat of that ugly word “scab” being thrown at them, at their wives, or at their children as they go to school

. . . even if Mr John Redmond attempted tomorrow to assume the responsibility of Larkin, the conscience of Ireland would be so revolted that within a week he would be looked down upon, despised, and ignored.’

Advanced nationalists

Many advanced nationalists were also hesitant as regards Larkin’s methods. Patrick Pearse did not know ‘whether the methods of Mr Larkin are wise methods or unwise methods (unwise, I think, in some respects)’. He did, however, know that there was ‘a most hideous wrong to be righted, and that the man who attempts honestly to right it is a good man and a brave man’. Pearse believed that ‘the root of the matter’ lay ‘in foreign domination’. ‘A free Ireland would not, and could not, have hunger in her fertile vales and squalor in her cities.’ The anti-Larkinite Arthur Griffith was in no doubt as to ‘the wisdom’ of Larkin’s methods and saw him simply as a ‘representative of English trade-unionism in Ireland’. This feeling was shared by the editor of the Leader, D.P. Moran, who noted how ‘Irish Ireland does not stand for “hands across the sea”, it stands for Ireland a self-contained entity

. . . We don’t want to take our labour, politics, or our laws from England.’

The workers’ brief arousal from their servitude in the autumn and winter of 1913 had indeed, in the words of James Larkin, ‘shed a light in dark places’ for many amongst the wider nationalist public opinion in Ireland. The interest of respectable Catholic Ireland was as short-lived as it was unsympathetic, however, and, as James Connolly later noted, ‘the Irish worker must now go down into Hell, bow our backs to the lash of the slave driver . . . and eat the dust of defeat and betrayal’. HI

John White is a schoolteacher in Dublin whose research has focused on the Irish Revolution in counties Carlow, Kildare and Wicklow.

Read More : ‘Bad, sad specimens of the human race’: Prostitution

Further reading

E. Larkin, James Larkin, 1874–1947: Irish labour leader (London, 1965).

T.J. Morrissey, William Martin Murphy (Dublin, 2011).

J.V. O’Brien, Dear, dirty Dublin: a city in distress, 1899–1916 (Berkeley, 1982).

A. Wright, Disturbed Dublin: the story of the great strike (London, 1914).