ANGELA BYRNE

Royal Irish Academy

€30

ISBN 9781802050455

Reviewed by

Pauric Travers

Pauric Travers is president emeritus of St Patrick’s College, Drumcondra.

Irish historiography has not always had a happy experience of large, multi-disciplinary projects. The Royal Irish Academy’s Irish Historic Towns Atlas series is a notable exception. Ireland joined the European Towns Atlas initiative in 1986 with the publication of a Kildare atlas. The launch now of the Ballyshannon atlas—the 32nd in the Irish series—is a significant landmark. Individually and collectively, the atlases have made an important contribution to our understanding of the history of Irish towns; they have also provided an invaluable tool for the comparative study of urban development in Ireland and across Europe.

The Ballyshannon atlas is a welcome addition. Even allowing for the uneven pattern of urban development, the west—and particularly the north-west—has been under-represented in the series. As a relatively small town, Ballyshannon offers an interesting case-study which in some respects is quite distinctive.

The format follows a well-established pattern: 21 printed maps are enclosed in a fascicle or folder along with nine plates (images), including Thomas Roberts’s striking painting of the town in 1770 (opposite page), an introductory essay, topographical information and a detailed bibliography. The introductory essay by Angela Byrne is authoritative and informative: it provides an essential context and a concise commentary on the maps included. The availability of the atlas digitally is an added bonus. While the fascicle format is flexible, it suits students, teachers and researchers better than casual readers.

Ballyshannon ticks at least four of the standard boxes for reasons for the location of a town: ford on a river (the Erne), strategic location in the landscape (fertile plane to the south and more mountainy land to the north), a seaport and a nearby monastery (the Cistercian Abbey of Assaroe, founded in 1178). Whatever the truth of the oft-repeated local claim that Ballyshannon is the oldest town in Ireland, it has certainly been the location of settlement from early times. While this early and medieval history is sketched briefly, the focus of the atlas is the development of the town from the early seventeenth century after the Tudor conquest and the Flight of the Earls.

The ford on the Erne at Ballyshannon was a strategic gateway to Tír Chonaill. That was why Niall Garbh Ó Domhnaill built a castle on the high ground in 1423. It is why the English laid siege to the castle during the Nine Years War and why the area was included in the Plantation of Ulster that followed. The various military installations which were subsequently built were called upon repeatedly—in 1641, during the Williamite period, in the 1790s and in the Irish revolutionary period of 1912–22. At the time of the Tudor conquest, the English captain Thomas Lee identified the ford as a crucial passageway for the rebellious Irish. More than 300 years later, during the Irish Civil War, when republicans were struggling to sustain their campaign in Donegal, Seán Lehane of the beleaguered republican First Northern Division made the same point in a despatch to headquarters, lamenting the obstacle posed by the narrow fourteen-arch bridge, built in 1680.

Maps are not value-free—they are freighted with political context and imperial purpose. John Thomas’s colourful map of the Battle of Ballyshannon (1594) records the attempt by English forces to assert control over the rebellious Gaelic lords of Tír Chonaill and Tír Eoghan by laying siege to the O’Donnell castle at Ballyshannon. Several of the maps that follow chart the story of the attempt to plant civility in the shape of English and Scottish settlers. The Ordnance Survey (OS) maps from the 1830s, which are the core of the atlas, also reflect a deeper cultural and political context, memorably explored by playwright Brian Friel in Translations.

Ballyshannon was granted a market in 1608 and incorporated by a charter of James I in 1613. The town developed slowly and reached its apogee in the latter part of the eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth century. A thriving commercial and mercantile community was underpinned by a busy port, which traded with maritime centres in northern Europe and across the Atlantic. This is evident in the OS maps and in an invaluable map reconstructing the town as it was physically, socially and economically in 1835.

The population peaked in 1821 and then fell, only to rise temporarily in the 1840s with the influx of famine victims from the surrounding districts before falling again steadily thereafter. Not all of this decline can be attributed to the Famine: a sand bar in the estuary, changes in international shipping and the coming of the railways diminished the utility of the port. This was partially counterbalanced by the fact that until 1960 the town was served by not one but two railways—the Great Northern Railway line from Enniskillen (1856) south of the river and the Donegal Narrow Gauge Railway (1905) on the north side.

Partition struck another blow, as it affected the business community and deprived the town of its natural hinterland. Historically the port and the River Erne had acted as a gateway to Enniskillen and mid-Ulster. The frozen politics of the post-partition period and the sundering of social and economic ties had a significant negative impact on border towns like Ballyshannon.

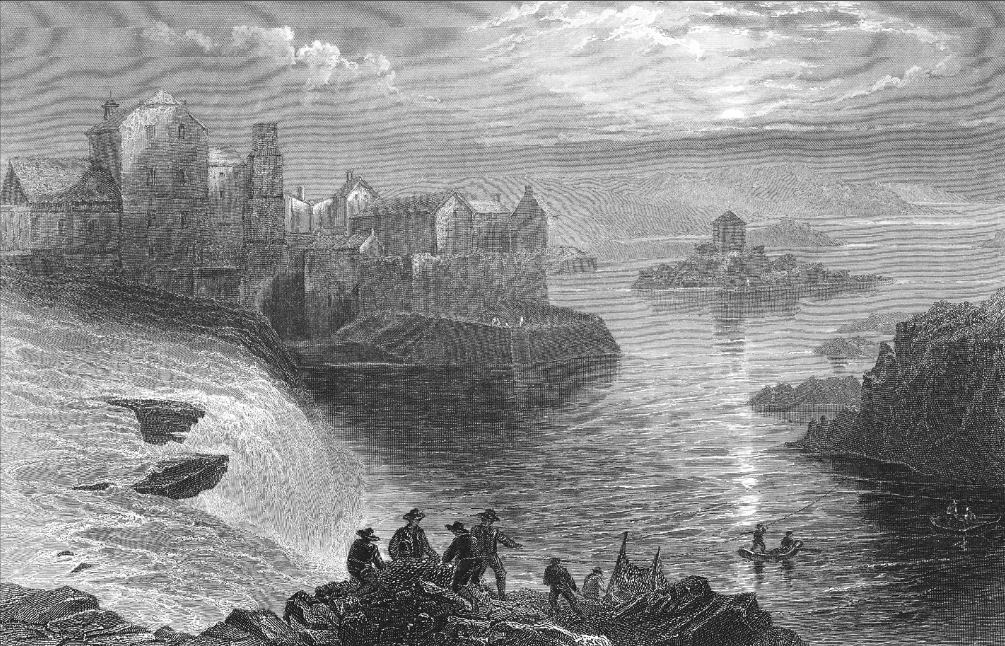

Angela Byrne comments that from the mid-eighteenth century the salmon leap at Assaroe Falls, dramatically illustrated in J.T. Willmore’s 1842 drawing (above), was counted among Ireland’s principal tourist attractions, alongside Wicklow, the Lakes of Killarney and the Giant’s Causeway. The poet William Allingham once wrote that Ballyshannon had a voice of its own, which came from the sound of the falls. That voice was silenced in the 1940s with the building of a hydroelectric station, which involved narrowing the river and removing the falls. A short-term boon to the town (and a long-term benefit for the country), the project damaged valuable fishing grounds and destroyed a lucrative tourist attraction.