By Fergal Lenehan

Diplomatic relations between Ireland and the German Democratic Republic (GDR) began formally only in 1980. Prior to that, a relatively small number of Irish people visited the GDR, while the Belfast-born illustrator and children’s author Elizabeth Shaw would appear to have been the sole person born on the island of Ireland who lived permanently in East Germany. Shaw was resident in East Berlin from 1946 until her death in 1992. Recent journalistic articles from the websites of the BBC and RTÉ have called Shaw respectively ‘the Irish artist who charmed East German children’ and ‘the unknown Irish writer behind an East German children’s classic’.

BACKGROUND

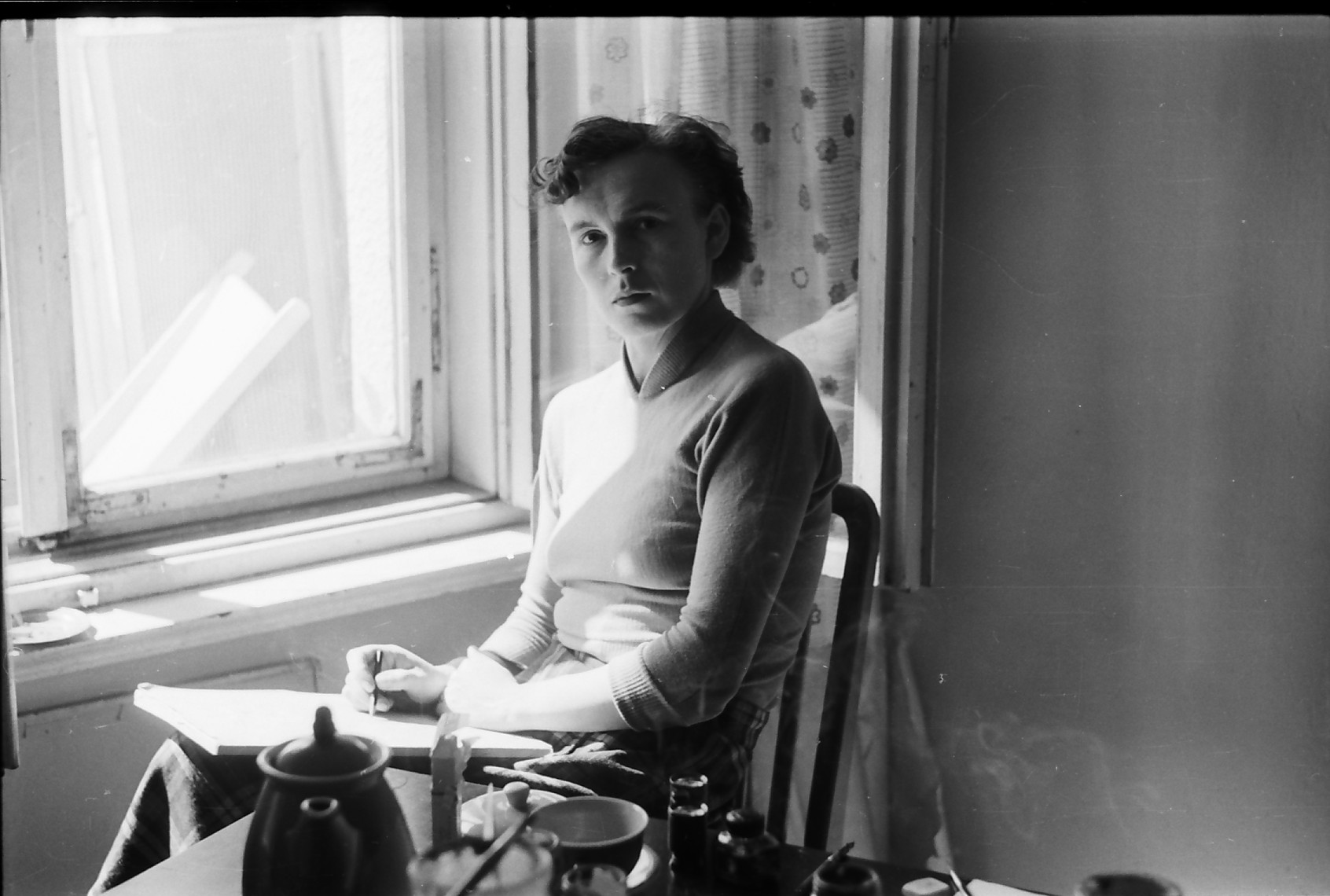

Shaw’s life is unquestionably unique. She was born in Belfast in 1920 to a bank manager father from County Sligo, a member of the Church of Ireland and a Home Rule supporter, and a Presbyterian mother from rural Armagh who disrupted her studies at Trinity College, Dublin, to marry Shaw’s father. Shaw grew up in a middle-class family that saw themselves as Irish. When Elizabeth was thirteen, and upon her father’s retirement, the Shaws moved to an affordable house in Bedford, England, having earlier considered a move to Dublin. Elizabeth discovered her talent for drawing and went to art school in London, where she concentrated on book illustration. At the Chelsea School of Art she was introduced to Marxism, became involved in London communist circles and later, during the Second World War, began a relationship with the émigré German artist René Graetz, who was born in Berlin but raised in Switzerland. In 1946 Shaw and Graetz, who was a committed communist, married and decided to move to the Soviet Zone in Germany to help rebuild the German state in accordance with their anti-fascist ideals.

Shaw became a freelance artist, often working as an illustrator and caricaturist for the mainstream GDR press. Eventually she wrote and illustrated her own children’s books, which became exceptionally popular in East Germany, especially her first book, Der kleine Angsthase (The timid rabbit), from 1963. This ‘became one of the most popular children’s books in East Germany’, according to Sabine Egger. A number of her stories were turned into children’s ballet performances during the life of the East German state and Shaw won a number of prestigious GDR book prizes. And her books are still widely read by children, and their parents, in today’s unified Germany.

CARICATURES

Before becoming a well-known children’s author and illustrator Shaw worked as a caricaturist for the daily newspaper Neues Deutschland, among other publications. Neues Deutschland was the central organ of the SED, the GDR’s socialist party, from 1946 to 1989. Shaw contributed caricatures which are completely in line with the propagandistic media discourses dominant in the GDR. These include caricatures that were deeply anti-American and anti-West German, portraying both states as fascist and warmongering, while the Soviet Union was depicted as a paragon of peace. She also produced caricatures that warned about the ‘enemy within’ and to be cautious of enemy saboteurs and agents. The increased paranoia of GDR society is to be seen in Shaw’s newspaper caricatures, which need to be analysed in terms of their time and context.

SHAW AND GRAETZ IN THE STASI ARCHIVES

Elizabeth and her husband, the sculptor and painter René Graetz, were members of the East German cultural élite. Shaw was a British passport-holder who enjoyed free movement and travelled widely, beyond the GDR. It would make sense, then, if the Ministry for State Security, the infamous Stasi, kept a close eye on them. I went to the federal archives to find out. The Stasi archives are closely guarded and not open to everyone, and this was only possible as Elizabeth Shaw is regarded as a public figure.

Shaw’s file was quite thin, but it did contain an ‘Investigative Report’ from 1966. What was striking, firstly, was the number of spelling and factual errors to be found in this Stasi document. For example, she is described as having been born in ‘Bedfort, Irrland’; Bedford (not Bedfort) is the capital of Bedfordshire in England, while the German spelling for Ireland is actually Irland not Irrland. In the present age of extensive digital surveillance, it is also notable that the report is based on discussions with Shaw’s neighbours and a perusal of the local police files (which contain records of journeys abroad). The author of the file also states that they could not find out where in East Berlin Shaw actually had her studio—hard to imagine in the present age, when Google has so accessibly mapped and photographed our streets.

Elizabeth Shaw is described as someone who sympathises strongly with the SED, the East German socialist party, and the politics of the GDR government. Shaw and her family live in very good financial circumstances, according to the report. They have a six-room apartment—still very good for Berlin—and their own car, but not full-time servants or house staff. Shaw and her family are friendly with well-known artists, journalists and architects, some of whom lived in England during the war, while they do not have large gatherings. The report details Shaw’s family connections to England, while connections to other artists in the GDR, West Berlin, West Germany and abroad are ‘presumed’. Shaw’s trips abroad since 1961—and the building of the Berlin Wall—are detailed and include four family holidays to England, a work trip to Czechoslovakia, two holidays in Bulgaria and a holiday in Romania. Given the difficulty of travel at this time, especially in East Germany, this is an impressive list.

The report ends with a few sentences on René Graetz. He is seen in the area as a ‘dependable comrade’ and has a ‘good reputation as an artist’. According to the Stasi employee who wrote the document, he has the demeanour of a Frenchman, in terms of clothes and body language (Graetz had grown up bilingually in Geneva, with a German father).

DIFFERENT PICTURE BY 1970

Parts of a heavily redacted report from 1970 on René Graetz were also to be found in the archives and paint a very different picture. Graetz had worked in the dominant social realist idiom as a sculptor and painter, but in 1970 he changed direction and began to work in a more abstract and experimental form, which he continued until his death from a heart attack in September 1974 at the age of 66. This change in style also reflected his changing attitude to the GDR system, which is reflected in the Stasi archives.

A Stasi internal communication from February 1970 states that Graetz had come back late from a work trip to England, but the author decides that this had probably to do with his wife’s extended family. A heavily redacted report from March 1970 is a lot more damning, at least from the perspective of East German state security. It describes Graetz as spending the war years in England, marrying Shaw there and being a member of the SED. It reiterates that he was part of a sculpture collective that executed the monument at Buchenwald concentration camp, for which he won a national prize. The author then writes: ‘Graetz is of the opinion that the cultural politics of the party are wrong, and artists do not have any freedom. He is for a western orientation.’ This is emphasised also with evidence from an ‘unofficial source’ whom Graetz informed in 1963 that he cannot express openly ‘his true feelings about art’ otherwise ‘his legs would disappear’. Thus in 1970 Graetz was no longer seen as a ‘dependable comrade’ but as harbouring aesthetic and perhaps political opposition to the regime.

This is in stark contrast to the representation of his wife, Elizabeth, in the same set of documents in the Stasi files, which are presumably also part of the March 1970 report (the document is so heavily redacted that this is not completely clear). Graetz and Shaw are described as having differing political opinions, but this has not had consequences for their marriage. Shaw is a member of the SED, ‘discusses positively’ and retains political clarity. The author writes in relation to Shaw: ‘The respondents replied that she was politically the opposite of her husband’. Thus a clear political difference is evident here between the Belfast-born GDR artist and her husband.

A further, again heavily redacted, page from the same set of documents has now a rather chilling effect. It details ‘positive people in the area’ who are ‘dependable’ and who live close by, some of whom are even members of the East German police. All of the names are redacted, but this part of the document ends with the mention of a person or persons ‘living on the ground floor with good circumstances for a possible observation’.

René Graetz had definitely become a person of interest for the Ministry of State Security by the early 1970s, as they began pondering a possible closer observation. This might indeed have happened had he not died in 1974 from a heart attack. Would he have become a dissident from a left-wing perspective, disillusioned with authoritarian socialism and its lack of freedoms? Would his Belfast-born wife Elizabeth Shaw have changed her mind also and come to be seen as less ‘dependable’? We will never know.

Fergal Lenehan teaches and researches at the University of Jena.

Further reading

S. Egger, ‘The unknown Irish writer behind an East German children’s classic’ (https://www.rte.ie/brainstorm/2021/0706/1233384-elizabeth-shaw-der-kleine-angsthase-the-timid-rabbit/).

F. Lenehan, ‘Back in the GDR’, Dublin Review of Books, 16 December 2013.

F. Lenehan, ‘Elizabeth Shaw from a transnational perspective: the intercultural self, propaganda and Shaw’s representation in the GDR print media’, in G. Holfter, D. Byrnes and J.E. Conacher (eds), Perceptions and perspectives: exploring connections between Ireland and the GDR (Trier, 2019).

R. Sheeran, ‘The Irish artist who charmed East German children’ (https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-61604906).