RTÉ2, 1 November 2024 and RTÉ Player

By Sylvie Kleinman

‘Let’s make a documentary about it’: the popular podcaster and open discusser of his autism Blindboy Boatclub has co-written and presents The Land of Slaves and Scholars. Despite having no god or religion, he is fascinated by the Early Christian Irish writing tradition—literally, as we will see. But taking pride in this cherished pillar of Irish identity makes him queasy. Irish Christianity makes him think of the Catholic Church, abuse and victimisation. We’re concerned that the twentieth century will blinker the long journey backwards, but ‘finding out more’ about Early Christian Ireland, in an openly blatantly trendy manner, ends up in a credible demonstration. It may look a bit narrator-centric but it’s clearly a team effort. The F-word is liberally dispensed throughout to prove that history doesn’t have to be dull. Well, if academics appear rigid in RTÉ’s usually stiff and formulaic documentaries, it’s because they’re not granted the freedoms that Blindboy was. But he chats about the themes with contemporary scholars or ‘experts’ who seem more relaxed and enthusiastically engaged than in the old-school template. Among them, Niamh Wycherley and Daniel Curley are also listed as ‘factual consultants’.

In antiquity Ireland was covered with a dense forest, and the petty kingdoms had no centralised role. But as it had an oral culture, Manchán Mangan explains, ‘all of the encoded knowledge of the people’ about their forebears or the weather was retained in the mind of the druids. With no towns, the people had devised and built raised mounds as gathering places, and we were swept onto Rathcroghan (Co. Roscommon) with some weird fish-eye-lens hemispherical shots. This ancient royal site of Connacht was a hub of activity, brought to life by computer-generated imagery as Curley provided insights into its pagan festivals, which revolved around the seasons. We fast-forwarded to nostalgic TV footage of the Puck Fair, and how worship of the goddess Éire was linked to the land and its fertility, which ensured our survival. Books were not needed to relay stories that emerged from the landscape, of giants and goblins feuding, mediated by the river which flowed between them. To conclude this section, Blindboy got ‘conkers-deep in paganism’ by luring us down into the bowels of the awesome Oweynagat Cave at Rathcroghan. It’s mentioned in the Táin as the ‘gateway to the other world’, but these epics were written down by the monks, and Mangan ponders whether we can trust their (Christian) version. Hallowe’en began in this ‘Cave of the Cats’: monsters escaped but the people dressed up in grotesque costumes to frighten them away. Shots of a grim sky and birds swirling were quite effective.

Emerging into the daylight, Blindboy was ‘now ready for a bit of Christ’, conversion and monasteries. Yet ‘the lad’ on whom we’ve built our national identity, illustrated by Kodachrome footage of a St Patrick’s Day parade and more magnificent scenery, had not been our first Christian. Why don’t we have a pint, or even a martini, on St Declan’s day (and ‘bother a few Yanks’)? But disturbing inherited constructs and idealised monomyths, even in such an obviously jokey way, is already a healthy sign of questioning simplistic popularised tales of the past. The narrow and unscholarly anti-British agenda of Normans (reviewed in HI 32.5, Sept./Oct. 2024) had claimed that Ireland became a two-tiered society after and because of the conquest, but here learned interviewees discussed with Blindboy how pre-Christian Ireland was by no means a ‘social utopia’. Soon priests and monks legitimised kings by writing up their dynasties, thanks to the ‘new’ technology of writing (in our non-Romanised world, that is). ‘You’re not the king! F— you, it’s written in the book!’ The monasteries created ‘institutional memory’ but were also part of a power dynamic, as ‘posh’ families entered the ecclesiastical hierarchy, displayed patronage and made land grants. As economic power houses covering thousands of acres, their sustainability relied on enslaved labourers. We droned over ‘a peaceful lake’ to compensate for the ‘Marxism’ on RTÉ, but behind this unconventional humour interviewees directly addressed the realities of the times. ‘Slaves … slaves … slaves … slaves’, they all uttered in a composite sequence. Surrounded by re-enactors in a realistic, reconstructed settlement, casually filming themselves on their phones, Blindboy asked why we didn’t talk about the fact there were ‘a f—king lot of slaves in pre-Norman times’.

To understand hermits, ascetics and penitents we were taken to Skellig Michael and St Patrick’s Purgatory at Lough Derg. On the harsh heights of the former, basking in sunshine, charming little puffins distracted the narrator reflecting on mortality and eternity. The demanding physicality of the place spoke for itself, as we towered over massive drops to the sea, but then at Lough Derg Monsignor Flynn explained about stepping away from everything to better hear the voice of God, like the desert fathers in Sinai. Or perhaps, like Blindboy, some of them were neurodivergent. To get closer to how people lived 1,500 years ago, someone got tonsured exactly like a monk in a suburban barber’s.

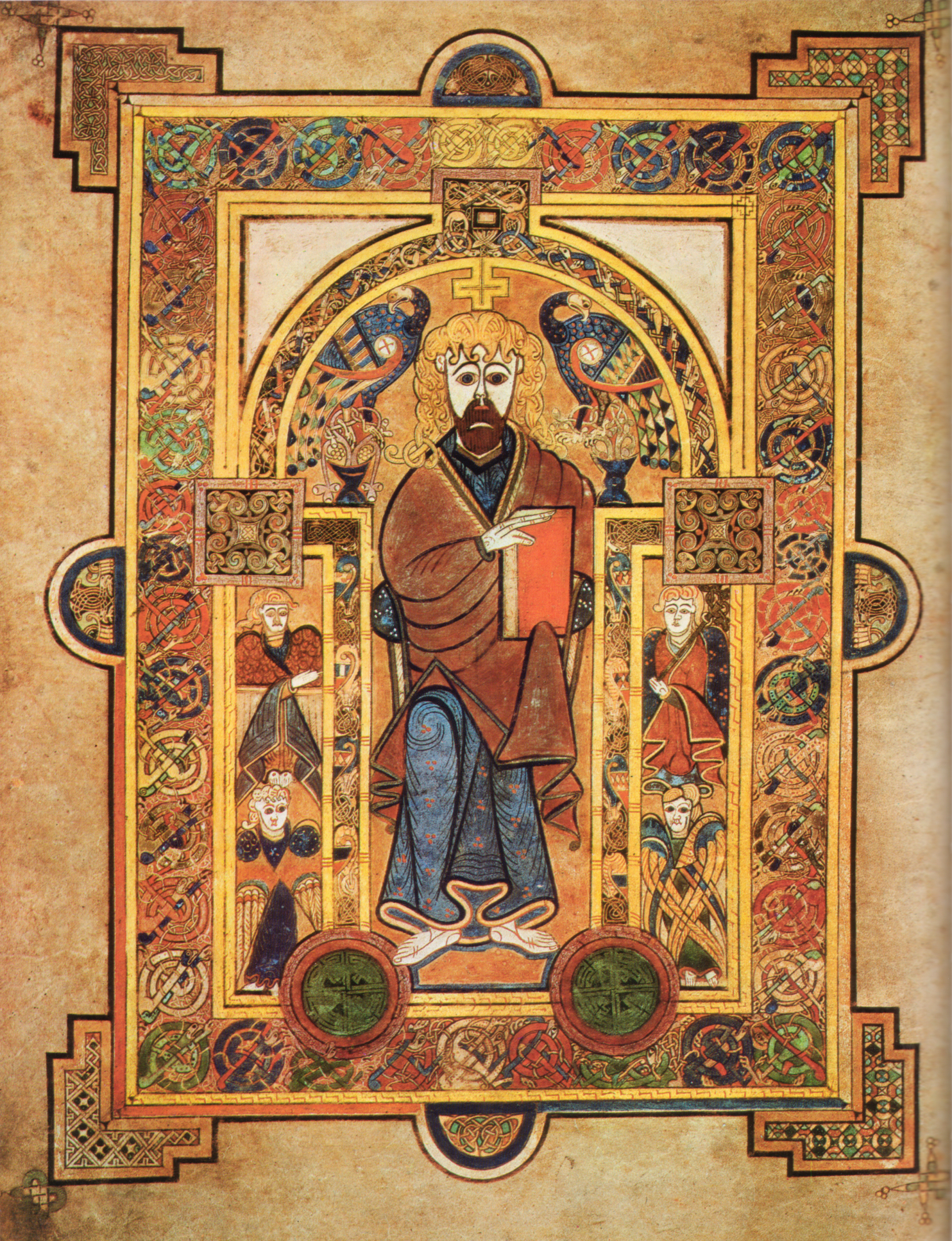

Next on to missionaries, scholars and artists. The wealth extracted by the monasteries enabled an Irish ‘golden age of intellectual output’, which the monks famously propelled into European culture. How did they manage without ballpoint pens and paper? We learned about vellum and, from historian and calligrapher Tim O’Neill, how inks were produced, e.g. green from malachite or red from lead—even from arsenic too, which is poisonous. ‘Take it out for the craic’: O’Neill produced a pouch which could have neutralised half a monastery.

With facsimiles from the Book of Kells, he showed how you could get four double-sided pages from one calf skin. He then effortlessly replicated the lettering with a flat-topped pen, and they discussed how it was Irish monks who had introduced spaces between words. They went ‘on the road’ in Europe, but we weren’t as important as we tell ourselves. Having listened to ‘the experts’, Blindboy now saw the ‘dirty tapestry’ of medieval history. Many rich seams are explored and RTÉ are now promoting this film for the Junior Cycle classroom.

The range of ancient sites and landscapes filmed is impressive, as is the flowing drone footage. Creative lens angles and distortions and oversized stark-lettered captions in dayglo colours give it a contemporary look, and obviously the presenter’s appeal and soundtrack will draw many to what appears trendy, but this innovative viewing experience is also supported by a well-researched and robust narrative.

Sylvie Kleinman is Visiting Research Fellow at the Department of History, Trinity College, Dublin.