The Blueshirts are best remembered as Ireland’s fascists, and as such there has been a tendency not to examine the broader activities of the movement. Between the image of a non-constitutional army, and the highly important role the Blueshirts played in the formation of the entirely constitutional Fine Gael, historians have struggled to give the Blueshirts an identity—indeed, there has been a tendency to ignore them or marginalise their effect on Free State political life.

The Blueshirts are best remembered as Ireland’s fascists, and as such there has been a tendency not to examine the broader activities of the movement. Between the image of a non-constitutional army, and the highly important role the Blueshirts played in the formation of the entirely constitutional Fine Gael, historians have struggled to give the Blueshirts an identity—indeed, there has been a tendency to ignore them or marginalise their effect on Free State political life.

From the small amount of writing dealing with the movement, two overviews do predominate. The first championed by Maurice Manning (The Blueshirts [1971]) and F.S.L. Lyons (Ireland since the famine [1971]) see the Blueshirts as part of the old Civil War groupings still struggling to determine future political ascendancy. The second favoured by Paul Bew, Ellen Hazelkorn and Henry Patterson (The Dynamics of Irish Politics [1989]) views the Blueshirts as a rural based and highly conservative movement which was coloured by the personal fascism of its leader, General O’Duffy. The confusion over the Blueshirts’ place in Irish politics continues, reinforced by the common use of the term Blueshirt in modern by political and popular discourse. John Waters (Jiving at the Crossroads [1992]) offers countless examples of the process that still leads to any supporter of Fine Gael being referred to by their opponents as a Blueshirt. Such common usage of the term only serves to confuse any attempt to properly understand the movement.

Previous debate surrounding the Blueshirts lacks recognition of a central theme which was of the utmost importance to the leaders and the members; the movement’s sporting and social life. In the initial stages the provision of a sporting and social life for members was an attempt to boost membership and cement unity within the Blueshirt ranks. In this the Blueshirts show similarities to the British Union of Fascists and its sporting clubs in the East End, and countless other authoritarian movements (of both the left and right). More generally the Blueshirts’ sporting and social life should be seen as an excited response to mundane rural Ireland during the 1930s, and as part of a tradition common to previous Irish social and political movements.

The origins of shirted socialising

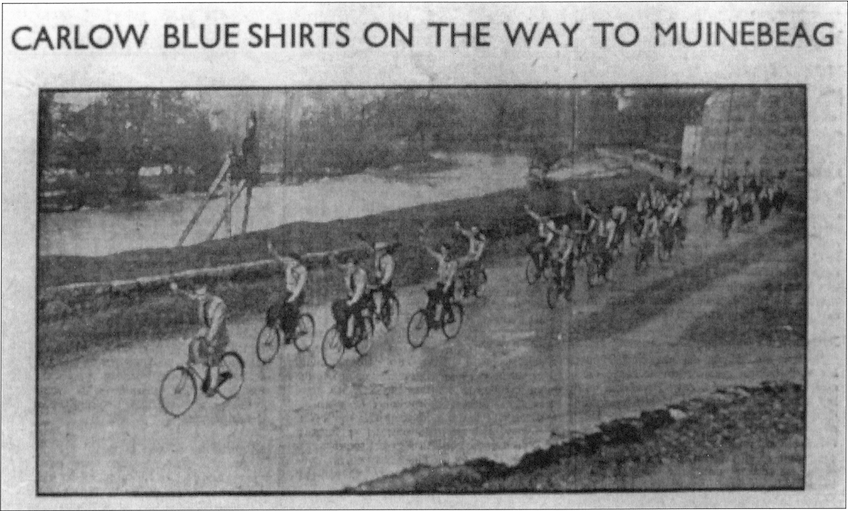

From its beginnings amongst individuals in the local branches during 1932, the idea that the Blueshirts would have a sporting and social agenda became part of the movement’s official policy. The headquarters staff in Dublin used this agenda solely as a vehicle for political gain, but the members predominantly saw the events as a source of personal amusement and recreation-not as an illustration of political strength. The official adoption of a sporting and social life began in April 1933 with the issuing of Order Number Two from the Dublin Headquarters. It stated, ‘every company shall, if possible, organise immediately a cycle section which shall pay regular visits during the summer months to outside areas for the purpose of assisting in the organisation of new units and of stimulating recruitment’.

After the publication of that order, the Blueshirt hierarchy constantly encouraged the members to become active in sporting and social events. The three Blueshirt papers (The Blue Flag, The Blue Shirt and United Ireland) constantly reported all local and national sporting and social events, and always in a very positive light. United Ireland stated that

already blue shirted cyclists have begun to move about in several counties. Tipperary and Kilkenny in particular. I hear of new units being formed as a result of their keenness for duty. The advantage of the work of the new mobile units is that it will put some of our senior officers, who may have led rather sedentary lives since they left the army, into active service condition. One man who is very prominent in the organisation tells me that he has cycled more in the last three weeks than he has cycled for the past two years.

General Eoin O’Duffy

The encouragement of this aspect of Blueshirt life reached its peak while the movement was led by General O’Duffy. Despite his erratic political leadership, O’Duffy was widely respected at a personal level by the members and he did much to cultivate the sporting and social side of the movement. His previous career was dominated by his time as Commissioner of the Garda Siochána, but his first love was always sport. He was a leading light in the Gaelic Athletic Association, managed the highly successful Irish Olympic team in 1932, was a committee member of the National Athletic and Cycling Association and was one of the main organisers of the Tailteann Games in 1924. Whatever condemnations are made of O’Duffy’s political skills, his understanding of the positive benefits of sport and socialising was unparalleled. He had witnessed such advantages first-hand during the 1920s when he had cultivated the development of sporting clubs and social events for Garda officers. O’Duffy brought a real vigour into the Blueshirts at countless levels. In particular, participation of Blueshirt members in the social aspects of their movement reached new heights. He believed that the nation’s youth should be fit and disciplined and that this could be achieved through participation in sporting events. Equally he felt that the organisation of social events such as dancing would demonstrate the togetherness and liveliness of his followers.

The direct result of O’Duffy’s emphasis on a sporting and social programme produced a wave of events across the country. Ex-members recall a wide range of events including: dances, cycle rides, picnics, whist drives, boxing matches, sports days, gymkhanas, sweepstakes to raise funds, gaelic football and hurling matches. The programme of events were undoubtedly successful. Not only are they fondly remembered by ex-members, but the period of O’Duffy’s leadership of the Blueshirts and his encouragement of such a programme coincided with a growth in membership from 8,337 in October 1932 to 37,937 in March 1934 and 47,923 in August 1934. The bulk of new members were undoubtedly inspired to join because of domestically relevant political concerns (such as the economic war), but the presence of a sports and social programme also boosted membership.

Whist drives in Tagout

The Blueshirts’ social life was the envy of their opponents. Teenagers in rural Ireland during the 1930s were not traditionally offered an opportunity to socialise, hence the development by an organisation of a coherent programme was a novelty. An ex-member of the County Cavan Blueshirts, Dennis Reynolds, recalled, ‘locally when they [the Blueshirtsj organised the social stuff, the whole of the young Blueshirts went. It was a great attraction because the other side didn’t do anything like that. I suppose if you weren’t a Blueshirt you wouldn’t normally be getting to a social at that age, but we got to them, and there was great support for them’.

The existence of the Blueshirt socials, attended by hundreds of young men and women in uniform, created not only envy, but also deepened political schisms which were already firmly in place by the early 1930s. For the opponents of the Blueshirts, whether driven by political hatred or social jealousy, the movement’s dances and sporting events were an easy target for attack. The 1993 release of Department of justice files lists scores of violent incidents centred on Blueshirt socials. These included the burning of the Strokestown branch’s dancing platform in September 1934, assaults on Blueshirts building a dancing platform at Rylane in June 1934, the removal of and burning of blue shirts from members returning home after a dance in Dun Laoghaire also in June 1934, and an attack on a bus leased to Charleville Blueshirts travelling to a sports day in Limerick in August 1933.

An Irish tradition?

The motivations of a member of any political movement will always be difficult to fathom, and in the case of the Blueshirts it is especially complex. Sixty years have passed since the blue shirt has been seen in Ireland. The popular belief that the shirt represented the Irish flirtation with fascism may have led many exmembers to sanitise the whole period in their mind, choosing to remember their social, not their political lives. Despite this, there is a definite case for arguing that many Blueshirts saw their membership as an excuse for socialising and as a chance to liven up their locality. For them O’Duffy’s wider political aims such as his desire to see the Irish adoption of Pope Pius Xl’s Quadragesimmo Anno, are unimportant. Outside of the 1930s there are countless examples of Irish political movements (especially those with a nationalist agenda) attracting support because of their social agenda, and it is in this context, rather than a contemporary European one, that the Blueshirts should be seen. In looking for the reasons behind the popularity of a political movement, the simple needs of people, such as recreation and entertainment, should not be overlooked: especially in the light of the condition of Ireland in the 1930s a country still incompletely modernised and politically uncertain of itself. After the demise of the traditional fair in Ireland during the nineteenth century and the upheavals of the early twentieth century, sections of the populace would not only be receptive to any group preaching traditional and stabilising political ideas, but also to any group offering a social life.

The Blueshirt development of a sports and social life as an integral part of membership followed these traditional patterns which had existed for over one hundred and fifty years. The examples of such a process are numerous. Father Mathew’s Temperance movement developed recreation as an alternative to drink. Duffy and Davis combined the ideas of education and recreation to boost the membership of Young Ireland. O’Connell’s repeal movement held mass meetings on days traditionally connected with the old fairs and encouraging the same spirit of revelry. The Catholic Young Men’s Society arranged lectures, trips and amateur dramatics to amuse and educate its members. The Fenians were highly successful at using sport and recreation as a means of recruitment and as a cover for their political meetings. The Gaelic League boosted its membership, as the Blueshirts did, by admitting and mixing members of WH both sexes, thereby adding the attraction of ‘flirting’ socially to the learning of a language. During the critical early years of the twentieth century most Irish people were too preoccupied with issues of life and death to worry about recreation. But by the 1930s when some semblance of stability had re-emerged, the people once again demanded pastimes. The Blueshirts were able to meet that need within the broad framework of their political organisation, and they gained much support as a result.

Mike Cronin is History Research Fellow at Sheffield Hallam University.

O. MacDonagh, W.F. MandIe & P. Travers, Irish Culture and Nationalism 1750-1950 (London 1983).

J. Hoberman, Sport and Political Ideology (London 1984).