By Joe Culley

@TheRealCulls

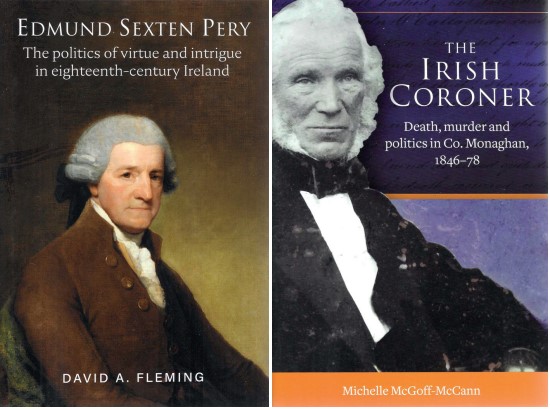

You will be forgiven for not having heard of Edmund Sexten Pery, and thus you will likely be surprised to learn that he was one of the great Irish parliamentarians of the late eighteenth century. How could the reputation of a man who was once so significant a figure as to serve as the long-time Speaker of the Irish parliament become so diminished over time?

In Edmund Sexten Pery: the politics of virtue and intrigue in eighteenth-century Ireland, David A. Fleming, a lecturer at the University of Limerick, tells the story of how Pery—pronounced then to rhyme with ‘cherry’—operated as a prominent ‘patriot’ for 30 years from the mid-1750s. Pery also played a significant role in the development of Limerick city.

As the blurb has it, Pery ‘was at the heart of political life and government in Ireland’. His ‘prominent role in shaping patriot ideology and the hidden part he played in securing “Free Trade” in 1779 and legislative independence in 1782 is explored in this biography, as are the successes and failures of the economic and urban projects he championed’.

Although this is an academic study, Fleming’s clear prose means that it is accessible to a general reader who already has an interest in the subject. For me, Pery comes across as the ultimate politician of the time (or all times?): loyal to certain ideals, open to exploiting personal ambition and profit, open to compromise and willing to negotiate with—and alternatively be distrusted by—all sides.

In a similar vein, Michelle McGoff-McCann’s The Irish coroner: death, murder and politics in Co. Monaghan, 1846–78 is another accessible academic work which will appeal to the right general reader. William Charles Waddell served as coroner of north County Monaghan for over three decades, and McGoff-McCann has had the good fortune to get her hands on his three casebooks. Such books are rare in Irish historiography.

Waddell was—not surprisingly—a steadfast Presbyterian among the Protestant élite in the alarmingly sectarian environs of Monaghan in the mid-nineteenth century. Indeed, in the previous decade one Sam Grey, a notorious Orangeman, had been going around shooting Catholics. He had been tried, and acquitted, twice by juries of his peers. Waddell had served on one of those juries.

Waddell’s new position, however, often put him at odds with the local élite, particularly when ‘cause of death’ impinged on power structures and politics. This became immediately clear with the arrival of the Famine. When is starvation not starvation? And who’s to blame?

‘Waddell’s inquests expose abuses of power and authority during a time when the county’s political life was controlled by a landowning, conservative elite. They helped to reveal to the public the injustice and corruption at the heart of county society.’

On a remarkably similar theme, but addressing a much earlier period, is Joanna MacGugan’s Social memory, reputation and the politics of death in the medieval Irish lordship. ‘Stories of murderous monks, tavern brawls, robberies gone wrong, tragic accidents and criminal gangs from court records reveal how the English of medieval Ireland governed and politicized death and collectively decided what passed for “truth” in legal proceedings’. Unfortunately, although Dr MacGugan’s writing is clear, the language is quite academic, as is the structure—there’s a 32-page ‘introduction’. The study also examines ‘Ireland’s place in the history of medieval literacy’. One aimed more at the specialist.

Most of you probably feel that you have a vague understanding of ‘the Tilson Case’: a couple in a ‘mixed’ marriage split when a Protestant father reneges on his pledge to raise the children as Catholics, and then the all-powerful Church ensures that the State enforces its wishes. And that’s where you’d be wrong. Sort of.

In the impressive The Tilson case: church and state in 1950s Ireland, David Jameson unpicks all of the preconceptions surrounding both the story and its legacy. Refreshingly, he begins by introducing us properly to Ernest Tilson and his wife, Mary Barnes, who wed in Dublin in 1941. Both came, to put it mildly, from humble backgrounds, and it is fair to argue that at least part of what drove Ernest to his decision was the squalid conditions in which the family were living in Turner’s Cottages in Ballsbridge. Significantly, Jameson was able to interview members of the family, including one of the sons who had been (briefly) installed in the Protestant-run Birds’ Nest orphanage in Dún Laoghaire.

The case went to the High Court, which ruled in Mary’s favour, and on to the Supreme Court, where Ernest lost again. Commentators often assume that the case revolved around the ne temere decree, but Jameson explains how that wasn’t at issue. But how did the case even get to the courts? Who paid the costs? And to what extent did the religious beliefs both of the judges and of those in government affect the ruling? But don’t take my word for it: John Bowman says that this book is ‘essential reading for an understanding of 1950s Ireland’.

I first learned the tale of Ballyseedy 40 years ago from Breandán Ó hEithir’s Begrudger’s guide to Irish politics (still worth a read, by the way), even though by then I had passed by the (then) isolated monument numerous times. That atrocity, of course, features prominently in Owen O’Shea’s excellent No middle path: the civil war in Kerry. This very readable account has been widely praised and will appeal to anyone—even those unfortunates with no Kingdom blood in them.

The collection of essays County Cavan and the revolutionary years, published in 2021, began as a series of on-line lectures during the peak of Covid and various lockdowns. It includes a piece by Brian Hughes about an attack on the Avra RIC barracks in 1920. And you can imagine my distress to read that a certain ‘Michael Culley’ would later state, in an official claim for compensation to the Irish Grants Committee, that he had passed on information to the police before the attack—i.e. he grassed. In Mr Culley’s, um, defence, it appears that he was probably the son of a retired Catholic RIC man.

Other essays include John Dorney on the border counties generally during the War of Independence; Sinéad McCoole on the role of local women in the campaign; and the brief but fascinating memoir of Frank Dolphin, who had served as an intelligence officer with the West Cavan IRA.

Staying in the locality, the newest edition of the always well-done Breifne includes an interesting piece by Geraldine McGovern on her great-grandfather Brian McEnroy, who worked with the Land League and ended up in Sligo Jail (Gaol?) after the first prosecution in Ireland for ‘illegal assembly’.

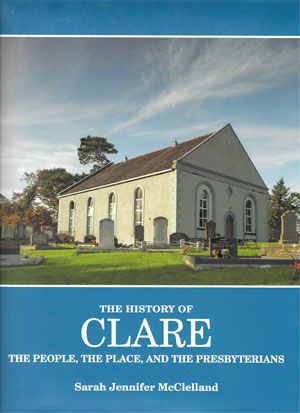

The rather extraordinary The history of Clare: the people, the place, and the Presbyterians gives a whole new meaning to the word ‘exhaustive’: this labour of love, an in-depth survey of a tiny community in County Armagh, is over 600 pages and weighs in at 3.7kg—that’s over half a stone in old money. Every wee parish/community in the land would be delighted with a similar production.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is all from me. After nearly eight years in the seat, this is my last Bookworm column. I’ve enjoyed it and I hope I’ve been able to direct you to a few of the many gems which go under the radar.

So, support your library, and safe home. Mind the buses.

David A. Fleming, Edmund Sexten Pery: the politics of virtue and intrigue in eighteenth-century Ireland (Four Courts Press, €58.50 hb, 320pp, ISBN 9781801510875).

Michelle McGoff-McCann, The Irish coroner: death, murder and politics in Co. Monaghan, 1846–78 (Four Courts Press, €40.50 hb, 254pp, ISBN 9781801510639).

Joanna MacGugan, Social memory, reputation and the politics of death in the medieval Irish lordship (Four Courts Press, €49.50 hb, 192pp, ISBN 9781801510905).

David Jameson, The Tilson case: church and state in 1950s Ireland (Cork University Press, €35 hb, ISBN 9781782055600).

Owen O’Shea, No middle path: the civil war in Kerry (Merrion Press, €16.99 pb, 282pp, ISBN 9781785374531).

Brendan Scott (ed.), County Cavan and the revolutionary years (Cavan County Council, pb, 165pp, ISBN 9870957165069).

Breifne 2023, vol. XV, no. 58 (Cumann Seanchais Bhreifne, €25 pb, 520pp, ISSN 0068087708).

Sarah Jennifer McClelland, The history of Clare: the people, the place, and the Presbyterians (self-published, £25 hb, 626pp, ISBN 9781909751972).