By Daragh Fitzgerald

The ongoing slaughter in Gaza has rightly produced outrage and consistent demonstrations of solidarity in Ireland, demanding a permanent ceasefire—as it has the world over. Irish support for the Palestinian cause is well documented and widely known. Less familiar, however, are the historic links between Irish nationalism and the Jewish diaspora. A perceptive and timely collection of essays, Forged in America: how Irish–Jewish encounters shaped a nation, documents some of these interactions, while more broadly it illustrates how Irish and Jewish immigrants in America engaged with one another in areas such as public health movements, fine arts, film and literature, romance, education, sport and beyond. Jewish immigrants to America encountered many people from backgrounds with which they were very familiar—Poles, Russians, Germans—and the long-standing animosity and persecution directed towards Jews by these groups was often replicated in the US. While Ireland had a small but significant Jewish population, the relationship between Irish and Jewish people did not have this same oppressive baggage and, although there certainly existed bigotry and tensions, there were also open-minded and mutually beneficial engagements. With themes of statelessness, exile, persecution and aspirations for a nation state, American Zionists perceived in the Irish struggle reflections of their own, while prominent cultural nationalists such as Aodh de Blacam and the sometimes-antisemitic Arthur Griffith praised the Zionist project, which was pursuing its own cultural revival and proved far more successful in reanimating a dying language than did its Irish counterpart. During the Great War both state-side Zionists and Irish republicans adopted a decidedly pro-German stance, while both had their hopes raised towards the end of the conflict by the Wilsonian moment. There were, of course, differences too—the topical Arthur Balfour has a very different resonance for both groups. By 1922 the Union Jack flew over governmental buildings in Jerusalem as it did in Belfast, but not in Dublin. A century later, the constitutional debate of both regions rages on.

Readers of History Ireland whose interest was piqued by Edel Bhreathnach’s article on the historical St Brigit in the magazine’s last edition and the History Ireland Hedge School exploring the same topic will be delighted to hear that Philip Freeman’s Two Lives of Saint Brigid facilitates direct engagement with the early Christian saint. Containing the hagiographies of Cogitosus and the anonymous author of the Vita Prima in both Latin and English, this text should be a great resource for future research and study on Brigit. Despite operating just a century or so after the death of St Brigit, Cogitosus would find a home in modern academia as a precocious practitioner of oral history, which he used to construct his account of Brigit’s life and works. Commentary throughout the text helpfully notes the various biblical references interspersed throughout the hagiographies, of which there are many. Perhaps most famously, Brigit is said to have adapted Jesus’s miracle at the Wedding Feast of Cana to suit an Irish audience, turning water into beer.

Whether offensive stereotypes or authentic representations, food and drink are key cultural signifiers of any nation, as any Irish person abroad sick of hearing potato- or Guinness-related jokes will attest. Feast—food—famine 1500–1800 explores the salience of food in early modern Ireland, with essays detailing how key societal changes that occurred in this period of enormous flux affected food—or lack thereof—as it related to Ireland. Ireland’s colonial experience was inseparable from the food culture of the island, as more broadly imperialism in this period came to greatly influence Western consumption and tastes—from where do sugar, coffee and chocolate originate? The collection is the result of last year’s (ninth) Mícheál Ó Cléirigh Summer School, held in the Franciscan Friary, Rossnowlagh, Co. Donegal. This year’s—from Friday 10 to Sunday 12 May, will focus on ‘Words, Language, and Lore’.

Although Harry Clarke is the Dublin name most associated with stained-glass windows, Michael Healy 1873–1941: An Túr Gloine’s stained glass pioneer is a stunning book that presents the story of his reclusive contemporary, who emerged as a pioneering artist prior to Clarke, Evie Hone or Wilhemina Geddes and set the bar for artistic and technical excellence in the stained-glass world. Healy was raised in a Dublin tenement and worked for the world-renowned An Túr Gloine studio for almost four decades, producing masterpieces that can be seen in churches across Ireland and the world, from Newfoundland to Malaysia. In his spare time Healy was an avid people-watcher, drawing hundreds of rapidly executed pencil and watercolour sketches of Dubliners going about their daily lives.

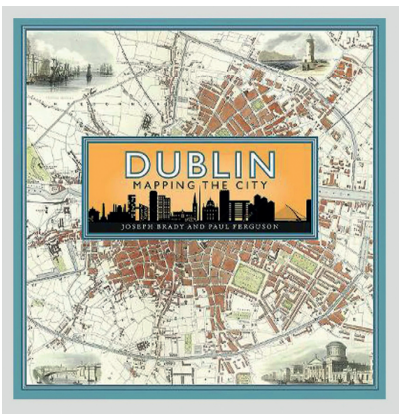

Archaeology tells us that Dubliners like those captured by Healy have been traipsing the city for centuries. The Vikings’ longphort is usually dated from 841, while Ptolemy’s maps from the second century depict a settlement called ‘Eblana’ near what is now Dublin. While this is almost certainly not Dublin, unfortunately no map from the Viking Age has been found, nor have any others dating from before 1610, when John Speed produced the first surviving detailed map of Dublin, which is itself the first map analysed in depth in Dublin: mapping the city. Tracing the development of Dublin through the prism of various maps produced over the centuries, Mapping the city evocatively displays the grandeur of the Georgian city at the height of the Protestant Ascendancy, the decaying typhoid-riddled tenements of the Victorian period and right up to visions of a future Dublin with an underground metro. Another highlight is Goad’s fire insurance plan from 1926, which illustrates the devastation on Sackville/O’Connell Street caused by the Civil War, an area still reeling from the Easter Rising ten years earlier. James Stephens, novelist and friend of Thomas MacDonagh, claimed that soldiers who served in the Great War and saw the destruction of the Sackville Street area compared it to that of Ypres, and Mapping the city charts the reconstruction efforts of this part of the city in the aftermath of the revolutionary period.

The drama and theatrics of the Easter Rising naturally draw much of the spotlight, so it is a nice change of pace to read about the less-glamorous tasks involved in picking up the pieces, which is also reflected in Offaly Heritage 12. This is an excellent collection of essays focused on the history of the Faithful County, particularly during the revolutionary period, and contains an entry discussing Offaly residents’ claims to the Property Losses Committee, which was established in the wake of the Rising to recompense those whose property was damaged in the rebellion. Unsurprisingly, Dublin’s most infamous capitalist, William Martin Murphy, owner of Clery’s, the Imperial Hotel and the Independent newspaper, which were all based in the vicinity of the GPO, was a prime mover behind this scheme, pressuring the Irish Parliamentary Party and the British government to provide compensation to business owners left with no greasy till to fumble in. The chief loss suffered by Offaly natives seems to have been watches which were left in Hopkins and Hopkins’ repair shop on the corner of Eden Quay and Sackville Street, destroyed in the course of the Rising. Arthur Orr of Cloncraine Lodge unsuccessfully sought remuneration for seven guns taken from his home by ‘Sinn Féiners’. Ironically, it was Tullamore ‘Sinn Féiner’ Peadar Bracken, appointed captain of the Kimmage garrison, who captured Hopkins and Hopkins during the Rising.

Those like Bracken who fought ar son Saoirse na hÉireann on Easter Week were awarded medals for their service, which, like the memorial at the GPO, depict the death of Cú Chulainn, hanging on a green and orange striped ribbon. This and many other State medals from the revolutionary period, the Emergency and beyond are detailed in Irish State Awards Emergency and Commemorative Medals: a guide for the collector and historian, which will also surely aid future generations when clearing out their revolutionary ancestors’ attics.

While the humanities have been under a sustained attack from the neo-liberalisation of universities in Ireland and abroad, the future of history-writing remains promising, if Trinity College’s new student history magazine, Then and Back Again, is anything to go by. Offering a historian’s perspective on current events and popular culture, with articles as Gaeilge as well as in English, the magazine is sure to be a hit, with this first edition featuring insights on the de-naming of the Berkeley Library and ‘the other Oppenheimer’, Mikhail Kalashnikov, to name just two. I am already looking forward to their future output.

Hasia R. Diner and Miriam Nyhan Grey (eds), Forged in America: how Irish–Jewish encounters shaped a nation (New York University Press, €30 pb, 288pp, ISBN 9781479826070).

Philip Freeman (ed.), Two Lives of Saint Brigid (Four Courts Press, €19.95 pb, 192pp, ISBN 9781801511162).

Tony Linehan (ed.), Feast—food—famine 1500–1800 (Mícheál Ó Cléirigh Summer School, €10 pb, 139pp, contact info@mocleirigh.ie).

David Caron, Michael Healy 1873–1941: An Túr Gloine’s stained glass pioneer (Four Courts Press, €55 hb, 400pp, ISBN 9781801510813).

Joseph Brady and Paul Ferguson, Dublin: mapping the city (Birlinn, €35 hb, 272pp, ISBN 9781780277516).

Michael Byrne, Mary Jane Fox, Ciarán McCabe, Ciarán Reilly and Lisa Shortall (eds), Offaly Heritage 12 (Esker Press, €18pb, 512pp, ISBN 9781909822337).

Ger O’Connor, Irish State Awards Emergency and Commemorative Medals: a guide for the collector and historian (€10pb, 39pp, ISBN 9781399953443).

Trinity Journal of Histories, Then and Back Again (Trinity Publications, 42pp).