By Daragh Fitzgerald

Turning and turning in the widening gyre, it is tempting to escape to the Otherworld, where the ‘Other Crowd’ reside, while ours is upside down and the top keeps spinning. Yeats believed in the existence of fairies, as does my niece, who recently told me she saw some at the bottom of my parents’ garden. Who am I to contradict two such resolute authorities on fairies as a Nobel Prize-winner and a six-year-old? Fairy forts—grass circles with tree-covered mounds in the centre of otherwise smooth fields—have long been believed to be gateways to the Otherworld and are the topic of Irish fairy forts: portals to the past by Jo Kerrigan and Richard Mills. Somewhere between 45,000 and 60,000 such structures can be found dotted around Ireland today. In our folklore, fairies have played both benevolent and malevolent roles in the lives of those who crossed their paths, and countless stories regarding fairy forts and their inhabitants can be accessed online at Duchas.ie. Modern engineers and planners continue to avoid disturbing the fairies for fear of retribution. In 2015, when a large US pharmaceutical company announced that it intended to build a factory on the site of Knocklong fairy fort, countless objections from the public flooded in and local construction workers refused to participate. True to form, the company drafted in workers from elsewhere and persisted with their project in 2017. Perhaps the recent tariffs débâcle is Otherworldly retribution? Fairies were certainly recorded as having striking hair and complexions!

‘Holy wells’ were also believed to be portals to the Otherworld. A common category of holy wells is Tobar na Súl, believed to aid eyesight, one of the oldest examples of which is on Dalkey Island. Dalkey: an illustrated history charts the history of the area from this prehistoric past right up to the Dalkey of the late Maeve Binchy. Dalkey Island was once the site of a Viking slave-camp, and the name of the area comes from the Norse Dalk Ei, a translation of the older Irish Deilg Inis, meaning ‘Dagger Island’. Up to the late eighteenth century, the ‘King of Dalkey’ was crowned on the island on the last Sunday in August with lavish fanfare, as thousands of people watched amidst music, revelry and drinking. While this practice has since died out, I suspect that there remain royalists in Dalkey to this day.

One of the most important archaeological finds illuminating Ireland’s ancient past was that of Mount Sandel. Located on a high bluff overlooking the River Bann just south of Coleraine, over 100 flint axeheads were uncovered in the 1970s (Ulster’s first arms dump?). The history of the province from Mount Sandel to the Good Friday Agreement is detailed expertly by the late Jonathan Bardon in A short history of Ulster, an illustrated and abridged version of his definitive A history of Ulster. While the province is often associated with bitter conflict and division—that Ulster regularly gets its own histories distinct from ‘Ireland’ is a function of this—the province was of enormous historical significance long before the Ulster plantation, as the home of the Uí Néill, the site of the Bruce Invasion and the resting-place of St Patrick, the holiest site in Ireland (save Bodenstown for some). Bardon takes the reader on an evocative journey through the millennia and does not shy away from the thornier aspects of Ulster’s history. Indeed, the text is prefaced by his assessment of the Peace Process when it was in its infancy.

Conflict over religion, land and civil rights is not, of course, unique to Ulster in Ireland’s history. New perspectives on conflict in Ireland in the nineteenth century is a collection of essays on the theme of conflict in Union Ireland, containing chapters from Patrick Maume, Kerron Ó Luain and Michelle McGoff-McCann, amongst many other experts in the field. Refreshingly, the focus is not myopically on ‘Ireland’ the island, as William Jenkins’s chapter discusses conflict amongst the diaspora, specifically in Ontario. While this could sometimes be characterised as proletarian Catholics against bourgeois Protestants, French-Canadians added a third dimension to the mix, while Irish Catholics, usually of different regional backgrounds, were also frequently in conflict with one another.

‘The long gestation’ of the Irish revolution in the nineteenth century that boiled over in the first decades of the twentieth is crucial to understanding both the trajectory of the revolution and the cleavages, divisions and social stratification of modern Ireland. As Bernadette Whelan explains in her introduction to Rita McCarthy’s Forgotten lives: the story of the County Clare mother and baby home known as the County Nursery, 1922–1932, the combination of class, poverty, religion, contempt and the tendency to hide ‘problems’ in institutions characterised Irish society long before the establishment of mother and baby homes by the Irish Free State. This particular mother and baby home was opened in part of Kilrush workhouse in 1922, and for the ten years of its existence it was owned and funded by Clare County Council, laying bare these continuities. The conditions in the home were horrific: it was dilapidated, with no running water, no modern baths or lavatories, and no electricity. The doctor in charge at the home described the death rate of babies there as ‘appalling’. McCarthy’s meticulous research of the original archives, newspapers and oral histories ensures that this mother and baby home, and the women and children unfortunate enough to have experienced it, are not forgotten.

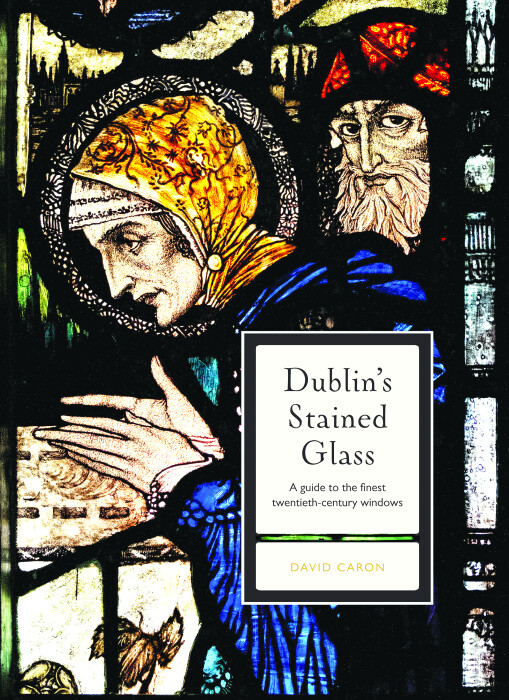

Dublin’s stained glass: a guide to the finest twentieth-century windows is a personal selection of the capital’s stained-glass windows by David Curon. During the twentieth century, Dublin was renowned globally as a centre for stained-glass excellence, with virtuosos like Harry Clarke, Wilhelmina Geddes, Michael Healy and Evie Hone all operating in the city. Most readers will be familiar with Bewley’s stained-glass windows, while those afraid of flying might be aware of the expressionist renditions of the Stations of the Cross in Our Lady Queen of Heaven church at the airport. These were created by Sheila Corcoran and initially removed at the insistence of Archbishop McQuaid, only to be reinstated more recently. Another highlight is a window in St Patrick’s Cathedral entitled ‘Chivalry’. Designed by William MacBride in 1917, the window depicts a knight with two angels and contains five shards of grisaille glass taken from Ypres Cathedral, destroyed like so much else by the Great War.

Nowadays, Ireland is renowned globally for its animation studios, which have achieved poster-boy status in the Irish film industry. There has been a stunning growth in Irish animation in recent years, documented by Steve Woods in Drawing the line: a personal look at the story of Irish animation. With studios working on 50 projects or so annually, with a total production value of €370 million in 2023, animation accounts for 50% of the South’s film production spend. Several Irish animators have been nominated for Academy Awards, including the studio Cartoon Saloon, creators of The Secret of Kells, Song of the Sea and Wolfwalkers, all instantly recognisable from their striking animation.

James Horgan is regarded as the first Irish animator for his short film depicting the Youghal clock tower coming alive and dancing around the town. The Horgan brothers: the Irish Lumières tells the story of James and his brothers Thomas and Philip, who were pioneers of Irish cinema. The Horgans were in fact major innovators of European cinema, and their portfolio included documentary photography, cinematic experiments and even the world’s first newsreel. Forgotten for a long time, their story has been recovered by Darina Clancy in this excellent book, along with its accompanying TG4 documentary, Na Lumière Gaelacha.

Joe Kerrigan and Richard Mills, Irish fairy forts: portals to the past (O’Brien Press, €19.99 hb, 256pp, ISBN 9781788495851).

John Martin, Dalkey: an illustrated history (Eastwood Books, €20 pb, 188pp, ISBN 9781916742680).

Jonathan Bardon, A short history of Ulster (Gill Books, €24.99 hb, 379pp, ISBN 9781804584057).

Paul Huddie, Cathal Billings and Arlene Crampsie (eds), New perspectives on conflict in Ireland in the nineteenth century (Liverpool University Press, €120 hb, 256pp, ISBN 9781836243892).

Rita McCarthy, Forgotten lives: the story of the County Clare mother and baby home known as the County Nursery, 1922–1932 (Banner Books, €20 pb, 170pp, ISBN 9781068505614).

David Caron, Dublin’s stained glass: a guide to the finest twentieth-century windows (Four Courts Press, €29.95 pb, 408pp, ISBN 9781801511674).

Steve Woods, Drawing the line: a personal look at the story of Irish animation (self-published, €25 pb, 194pp, ISBN 9781788463454).

Darina Clancy, The Horgan brothers: the Irish Lumières (Mercier Press, €20 pb, 224pp, ISBN 9781781178447).