By Joe Culley

@TheRealCulls

‘The murder of Ellen O’Sullivan in 1931 was a ghastly affair.’ That is, remarkably, the opening line of Capital punishment in independent Ireland: a social, legal and political history, the unusually accessible and—dare I say it—entertaining academic study by David M. Doyle and Liam O’Callaghan, published by Liverpool University Press.

‘The murder of Ellen O’Sullivan in 1931 was a ghastly affair.’ That is, remarkably, the opening line of Capital punishment in independent Ireland: a social, legal and political history, the unusually accessible and—dare I say it—entertaining academic study by David M. Doyle and Liam O’Callaghan, published by Liverpool University Press.

These sorts of publications are usually hard going, designed to meet the sometimes inexplicably demanding needs of some cold-blooded external examiner determined to adhere to the most rigorous academic conventions. Fortunately, someone involved in this project knows how to write—whether it’s Mr Doyle or Mr O’Callaghan I can’t say. It may be both, but it is unusual for a pair of writers—in any field—to merge into such a singular voice.

Don’t misunderstand me: all of the required academic rigour is here to support their theses, but it is presented within such lucid argument and storytelling that it weighs lightly on the casual reader. Of course, it helps enormously that there is a large element of ‘true crime’ in their subject. Who doesn’t want to read about the young woman married to an ageing farmer who ropes her nephew—and lover—into a plot to murder the poor man? And was she hanged? (Some were, others weren’t.) And if so, why?

The authors focus on three main areas: the death penalty as an instrument of State power and the political context in which it was applied; the key socio-historical features that emerge from the cases, e.g. the questions of gender or an urban/rural divide and such attendant social prejudices and hierarchies; and finally the move to abolish capital punishment.

Of course, given its provenance from a university press, Capital punishment in independent Ireland will set you back £80, so it’s best to order it from your library. (All of our readers are highly intelligent folk, so I’ll just assume that you have a library card.) To my mind, honestly, a more popular publisher should snap up the rights to this. A zippier title (the cover image is already good), a bit of editing and some scene-of-the-crime images—or, better yet, ‘artist’s renderings’—and you’ve got a winner.

Another engaging release is From landlords to genetics: the historical and modern story of the Trant estate, Dovea, Thurles, Co. Tipperary. Though it bears the name of local historian George Cunningham, he is quick to acknowledge the work of a large team of contributors.

Another engaging release is From landlords to genetics: the historical and modern story of the Trant estate, Dovea, Thurles, Co. Tipperary. Though it bears the name of local historian George Cunningham, he is quick to acknowledge the work of a large team of contributors.

The Trants were originally Danes who arrived in Ventry, Co. Kerry, in the late thirteenth century. One descendant, Sir Patrick, was a close associate of James II and followed him to France, dying there in 1694. In the ensuing centuries one branch of the family remained Catholic and became successful Cork merchants (they had their own quay, no less, and it seems that they engaged in the slave trade, as evidenced by an advertisement for the sale of ‘a black negro boy aged about fourteen’), while the other branch adopted the established religion and developed their Tipperary estate, just north of Thurles, from the 1730s.

It seems that Dominick Trant probably converted in the eighteenth century to practise law and climb various social ladders. In the late 1780s, in a notorious duel, he killed Sir John Colthurst, a landlord on the Cork/Kerry border. Colthurst had felt that Trant had libelled him in a pamphlet by suggesting that he was being too soft on the peasants and Rightboys of Munster.

It was Dominick’s son John Frederick who properly established the estate at Dovea. From the off he seemed enthusiastic to remove his tenants from the land by whatever means necessary, a practice his son John continued. There were extensive clearances during the Famine. During the Land War, John Trant was boycotted when he brought in ‘scab’ labourers from England. To be fair to the editors of the book, Trant gave his side of the story in a memorandum that he wrote in 1883, ‘Two years skirmish with the Land League’, which is reprinted in full. His daughter Hope’s happy memoirs of growing up on the estate are also included.

It was Dominick’s son John Frederick who properly established the estate at Dovea. From the off he seemed enthusiastic to remove his tenants from the land by whatever means necessary, a practice his son John continued. There were extensive clearances during the Famine. During the Land War, John Trant was boycotted when he brought in ‘scab’ labourers from England. To be fair to the editors of the book, Trant gave his side of the story in a memorandum that he wrote in 1883, ‘Two years skirmish with the Land League’, which is reprinted in full. His daughter Hope’s happy memoirs of growing up on the estate are also included.

After the Second World War, Captain Laurence Trant sold the land to the Centenary Co-Op, and in the 1960s it became a leading player in the technological revolution of AI (that’s ‘I’ for insemination, not intelligence).

It’s surprising to learn that Michael Doorley’s well-received Justice Daniel Cohalan 1865–1946: American patriot and Irish-American nationalist is the first proper biography of a pivotal figure in Irish-American relations. While Cohalan is best remembered here, particularly during this centenary period, for his falling out with de Valera, for at least 30 years ‘the Judge’ was focused on securing Irish independence while also promoting both the Irish in America and the interests of America in the world.

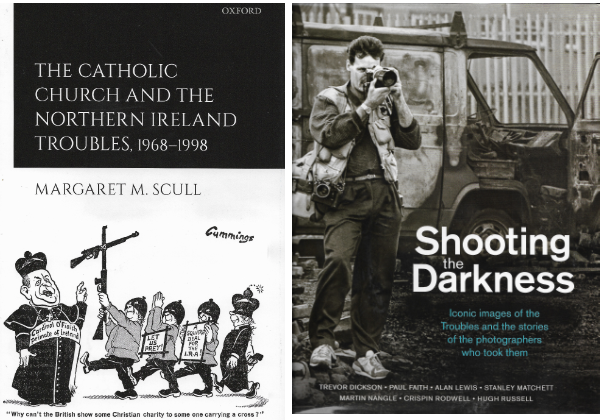

Margaret Scull, a postdoctoral fellow at NUI Galway, has examined the question of The Catholic Church and the Northern Ireland Troubles, 1968–1998. ‘During the Troubles … priests and bishops often worked behind the scenes, acting as go-betweens for the British government and republican paramilitaries, to bring about a peaceful solution. However, this study also looks more broadly at the actions of the American, Irish and English Catholic Churches, as well as that of the Vatican, to uncover the full impact of the Church on the conflict.’

Staying on that topic, you might have seen the fine television documentary Shooting the darkness: iconic images of the Troubles and the stories of the photographers who took them. There is now a handsome coffee-table companion piece.

At the start of 2018 the large-scale archaeological research programme ‘Digging the Lost Town of Carrick Project’ began to investigate properly the County Wexford site of the first Anglo-Norman fortification in the country, founded in 1169. The site is located in the Irish National Heritage Park. One of the main aims of the project, aside from the actual digging, was to make the general public more aware of the significance of the site.

To that end, Four Courts Press last year published Carrick, County Wexford: Ireland’s first Anglo-Norman stronghold, a series of twelve essays assessing the significant early findings of the project and to commemorate the 850th anniversary of the landings. As a companion piece, they have also republished the 2002 Arrogant trespass: Anglo-Norman Wexford 1169–1400 by the late Billy Colfer, which remains one of the standard works on the area and the period.

David M. Doyle and Liam O’Callaghan, Capital punishment in independent Ireland: a social, legal and political history (Liverpool University Press, £80 hb, 306pp, ISBN 9781789620276).

George Cunningham, From landlords to genetics: the historical and modern story of the Trant estate, Dovea, Thurles, Co. Tipperary (Dovea Heritage, €25 hb, 340pp, ISBN 9781527240360).

Michael Doorley, Justice Daniel Cohalan 1865–1946: American patriot and Irish-American nationalist (Cork University Press, €39 hb, 312pp, ISBN 9781782053521).

Margaret M. Scull, The Catholic Church and the Northern Ireland Troubles, 1968–1998 (Oxford University Press, £65 hb, 256pp, ISBN 9780198843214).

Trevor Dickson, Paul Faith, Alan Lewis, Stanley Matchett, Martin Nangle, Crispin Rodwell and Hugh Russell, Shooting the darkness: iconic images of the Troubles and the stories of the photographers who took them (Blackstaff Press, €22.99 hb, 134pp, ISBN 9781780732398).

Denis Shine, Michael Potterton, Stephen Mandal and Catherine McLoughlin (eds), Carrick, County Wexford: Ireland’s first Anglo-Norman stronghold (Four Courts Press, €22.45 pb, 242pp, ISBN 9781846827969).

Billy Colfer, Arrogant trespass: Anglo-Norman Wexford 1169–1400 (Four Courts Press, €17.95 pb, 316pp, ISBN 9781846828225).