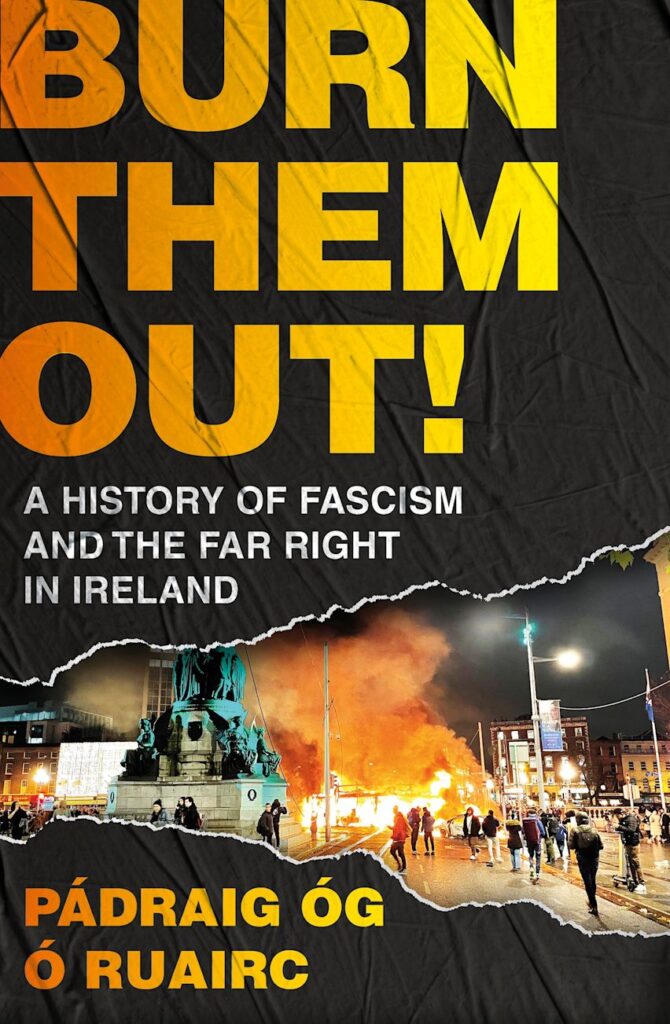

PÁDRAIG ÓG Ó RUAIRC

Head of Zeus

£16.99

ISBN 9781035915279

REVIEWED BY

Martin Mansergh

Martin Mansergh is Vice-President of the Irish Association of Former Parliamentarians.

In an era when, worldwide, heightened polemics are employed to gain and perpetuate the holding of power, this is a timely review of the situation in Ireland. The subtitle posits the affinity of fascism and the far right, without necessarily equating them. In the past it has been questioned whether the Blueshirts were ever a real fascist movement. That political sensitivity having gone, and given the efforts of the far right to establish an electoral foothold here, there is cause for a re-examination of the evidence, giving chapter and verse.

Pádraic Ó Ruairc’s book begins with Mussolini, a leader who wanted to make Rome great again. He boasted: ‘I see the world as it actually is, that is a world of unchained egoisms’, a sentiment enjoying a new vogue amongst ‘strong leaders’ today. Eoin O’Duffy’s banned march on Leinster House was, as he acknowledged, modelled on Mussolini’s march on Rome, echoed a century later by the assault of 6 January 2021 on the Capitol in Washington. The key element in fascism (and communism) was the replacement of representative democracy by dictatorship. Mussolini had imitators in Hitler, Franco and Salazar. He was a disaster for Italy, which had been much admired for the Risorgimento and unification. In 1944 de Valera made an impassioned plea to the Allies to save Rome. No thanks to Mussolini, it remains a great city.

There is an important chapter on Oswald Mosley’s Blackshirts, subsidised in the 1930s by Mussolini and heavily marked by anti-Semitism, which was closer to hand as a model for the Blueshirts. One of Mosley’s followers was Galway-born William Joyce, who during the war broadcast Germany calling from Berlin, much listened to in Ireland as a cross-check on the BBC.

A unique merit of democracy is that it legitimises political opposition and enables the people at intervals to change government peacefully. We should not underestimate post-Civil War turbulence. Historians rightly acknowledge the importance of the change of government in 1932, even if some outgoing ministers had had doubts about it. The British engaged vigorously in the economic war, hoping that de Valera would be swiftly replaced again by Cosgrave, but Fine Gael—formed in 1933, initially and briefly led by O’Duffy—had to wait sixteen years. Some leading figures, going by their public statements, lost faith in democracy. Ernest Blythe was for a time a thoroughgoing fascist. Even Yeats was briefly a Blueshirt. He once called O’Duffy’s politics ‘heroic’ and was constantly urging ‘the despotic rule of the educated classes’, given that ‘democracy is dead and force is the natural right’.

The core of the book concentrates on the street disorders resulting from repeated clashes between Republicans and Blueshirts. In 1933 the two leading parties each had the support of organised and unofficial parties of men which were a challenge to democratic government, to quote my father’s 1934 book The Irish Free State. The hostile Morning Post claimed that Ireland was really ruled by armed factions, with the Dáil doing their bidding. One should be under no illusions. If Ireland had become a fascist state, its survival could have been short-lived.

More analysis is needed of the role of the Catholic Church, led by Pope Pius XI. In 1929 a concordat with Italy and in 1931 the papal encyclical Quadragesimo Anno suggested that corporatism might provide an ideological alternative, based on Catholicism, to democracy. All this attracted interest in the Irish Church, which lobbied for early recognition of Franco. Clerical sympathy with Mussolini was quite widespread. Even Joe Walshe, secretary of the Department of External Affairs, was supportive of Vichy France, animated by conservative Catholic values.

Historians need to be wary of accepted generalisations. While James Dillon overtly challenged Irish neutrality during the Second World War, Cosgrave privately told the UK representative, Sir John Maffey, that the British had been mad to hand over the ports. In a 1942 UCD law debate, former Cumann na nGaedheal minister Paddy McGilligan criticised ‘neutrality as not worthy of Irish ideals’ and hoped that Ireland would end up siding with its ancient enemy. Similarly, Irish rejection of Jewish refugees was not blanket, as research directed by Gisela Holfter (University of Limerick) into the aftermath of Kristallnacht in 1938 has shown. Ernst Königsberger (Anglicised as Kingshill), though Lutheran, was of German-Jewish extraction and lost his job near Chemnitz. He was invited to Ireland to manage the Tipperary town glove factory. Gerald Boland, not Kevin, was minister for justice then. Another example was the Unger family of architects, Klaus later working for the OPW.

The book concludes with an overview of ephemeral fascist organisations in the 1940s and 1950s such as Ailtirí na hAiséirghe and ones founded by Commandant Brennan-Whitmore, as well as today’s glut of minnows that clutter up ballot papers and imagine that there is an opening for far-right politics in Ireland. Violent anti-immigration protests did not mobilise electoral support. For a small country, the leeway to go to extremes is limited. This may account for why governments here have always been led by one or other and now both of the two main parties. Embarrassing Loyalist alliances with British fascist or far-right organisations are also covered. Neither are attractive.