By Lorraine McCann

Amongst the array of documents found in the Louth County Archives are several registers of licences spanning the 1917–50 period created under the Cinematograph Act, 1909. This act, introduced in the United Kingdom, was primarily concerned with the safety of buildings to be used as cinemas as a consequence of fires in unsuitable premises. It placed the control of cinemas under local authorities (and the police), who became responsible for inspecting venues and issuing licences. Material relating to this activity in County Louth can also be found in the correspondence and engineering files, as well as in numerous discussions documented in council minute-books.

The regulations made under the act stipulated a host of conditions with which those wishing to operate cinemas were legally obliged to comply. These lengthy conditions were normally printed on the back of licences. Venues now had to have fire exits, projectors had to be enclosed in fireproof booths with a metal screen fitted to the opening that could be shut in the event of a fire, and the highly inflammable nitrate film had to be properly handled and stored. The fee for a licence in Dundalk and county areas was £1, while in Drogheda it was £1.1.0.

The earliest cinemas in Louth were Dundalk’s Foresters’ Hall, Town Hall and Park Street Cinema. The Dundealgan Electric Theatre Company opened the latter in October 1912, two months after the Town Hall was opened, while the Foresters’ Hall had obtained approval for a licence in May 1910. It was ‘reputed to [be] something in the nature of a small gold mine’, according to the Dundalk Democrat. The Electric Theatre soon obtained a tenancy agreement for Dundalk Town Hall, as documented in its engagement bookings register—an interesting record of concerts, plays, meetings and public events for those researching the social, cultural, economic or political history of the area in the 1906–28 period. They also obtained a tenancy agreement for Drogheda’s Whitworth Hall, a beautiful Victorian building on Laurence Street built in 1865 by the local MP, Benjamin Whitworth, who donated it to the people of Drogheda upon completion. It had its earliest film showing in 1914, and licences issued to the Dundealgan Electric Theatre for the Whitworth during the years 1917–26 can be found in Drogheda Corporation’s cinematographic licences register. This register also records licences from 1919–26 for the Boyne Cinema Company (1919–60; renamed the Savoy in 1954), operating out of the Oliver Plunkett Hall in Fair Street. This cinema had been established by Joseph Stanley, printer of the 1916 Proclamation and proprietor of the Oriel Cinema in Dundalk’s Foresters’ Hall (1919–52). Not long after opening, the Boyne Cinema came under the spotlight when the RIC confiscated a film named The Sinn Féin Review. A newsreel compilation, the film was being shown as a ‘special’ at the cinema that week and was seen as Sinn Féin propaganda, while police reports described Stanley as a ‘Sinn Féin suspect’.

In addition to the registers, minute-books also chronicle licences granted for cinemas as well as other cinema-related matters that arose, such as censorship, the attendance of children at performances after 7pm and the ban on Sunday opening. As Sunday was considered a day of worship, the Electric Theatre first proposed running ‘Sunday shows of entirely sacred pictures’ in the Foresters’ Hall in June 1910, but Dundalk Urban District Council ‘expressed themselves against shows of any kind on Sundays’. The council withstood repeated calls for Sunday opening but yielded to occasional shows for charity, hence the ban became less demanding. It was not rescinded until 1938.

Some applications met with refusal, such as the first application of Thomas McGivern of Blackrock, Dundalk, for a portable booth in 1934. In it, he described the hall as having two exits, a fire extinguisher, two buckets of water, a bucket of sand and a wet blanket. The booth, which measured 40ft by 20ft, was constructed of timber to the eaves with a canvas roof, floorboards laid on the ground and two exits that were each 4ft wide. Whereas McGivern confirmed that regulations were complied with, the county surveyor, Thomas Walsh, firmly reported that there was no automatic self-closing fire-resistant screen fitted to the projection openings in accordance with the regulations and would only grant a licence subject to this compliance. McGivern, who had ‘no other way of making my living and a family to support’, had to rectify the shortcomings without delay and his licence was duly posted.

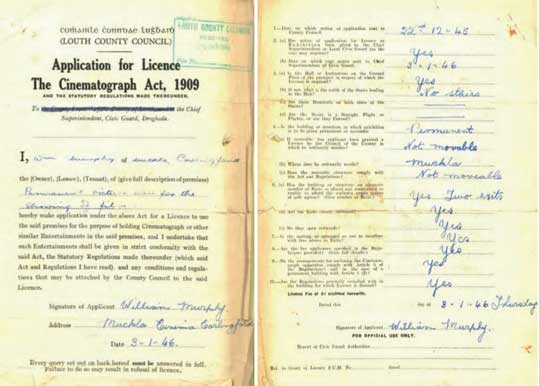

Elsewhere, William Murphy applied unsuccessfully to use the Mucklagh Hall, Carlingford, in 1938. The county surveyor did not recommend a licence as the hall, a lime and stone building, was not yet correctly fitted out, while the chief superintendent stated that owing ‘to the location of the proposed cinema and the difficulty of proper Garda supervision on that account the application cannot be recommended’. Murphy eventually obtained a licence for the years 1941–3.

Travelling picture-houses, touring ‘talkies’ and makeshift cinemas were common in rural areas, where no purpose-built cinemas were available. Some parish halls were adapted, with proceeds going towards parochial funds. These included the likes of St Mary’s Hall in Kilsaran and Kilcurry Hall in rural Louth, while in the town of Dundalk, which boasted six cinemas at one stage, the Magnet (1938–’70s) was run by Father Stokes for parochial funds, as was St Nicholas Hall (1951–69). This was juxtaposed with the successful commercial enterprise of the Adelphi Cinema (1947–99) in the heart of Dundalk, which had a capacity of 1,100 and where a restaurant and ballroom were soon added, making it a popular entertainment complex. Other commercial cinemas in Louth included two in Drogheda: the Abbey in West Street (1937–69) and the Gate at Westgate (1944–73), both with a capacity of 1,000; the Bohemian in Ardee (1940–79); and the Abbey in Carlingford (1947–63).

The attractiveness of early cinemas began to decline during the 1960s, perhaps owing to the growth of modern cinemas and the rising popularity of television.

Lorraine McCann is Louth County Archivist.