By Teddy Fennelly

The story of Col. Ned Despard, the Irishman who was hanged for treason in London in 1803, has been well documented but largely forgotten until it was brought before a new, and huge, audience when he was featured in a highly dramatic episode in the fifth series of the BBC romantic historical blockbuster Poldark, first shown in 2019 and now available on Netflix. Although it was a fictionalised account of the man and his times, the screened version portrays Despard authentically as a military man who had served his country well but, rather than being rewarded, is persecuted relentlessly by the establishment at Westminster because of his egalitarian views.

BACKGROUND

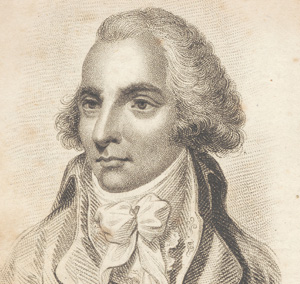

Ned (Edward Marcus) Despard was born in Coolrain, Co. Laois, in 1751 and came from Anglo-Irish Protestant stock with a Huguenot connection. He joined the British army as a teenager and, like most of his brothers, he made it his career. He fought in the American War of Independence and from Jamaica commanded British forces, backed by some local swashbucklers and mercenaries, in the West Indies campaign against the Spanish. In 1782 he commanded a successful expedition to recover the British settlement of Black River on the Mosquito Coast of present-day Honduras, which the Spanish had taken. He struck up a friendship with a young English sailor, Horatio Nelson, during this operation.

After a few early successes, their troops were hit by disease and desertions and were forced to abandon their hard-won territory. Despard displayed great bravery and leadership and was the last man to leave the besieged battle zone. Before he did, he made sure that Nelson, who was delirious with fever, was moved to safety from the conflict area, thus saving his life and enabling him to go on to achieve greater things in a distinguished military career which would culminate in the Battle of Trafalgar 23 years later.

SUPERINTENDENT OF BRITISH HONDURAS

The Peace of Paris of 1783 ended the American Revolutionary War and the conflict in the West Indies was thus brought to an end. In 1784 Despard took over the administration of British Honduras (present-day Belize). There he supported the land claims of recent immigrants who had been evacuated from the Mosquito Coast—an assortment of destitute black and mixed-race convicts and slaves who had nowhere else to go—against those of earlier settlers, who felt that they had first claim to the additional territory ceded to the colony by the Convention. The old Bay settlers, mostly plantation-owners who had done quite well from the logwood and mahogany trade, felt very aggrieved.

Despard’s humanitarian adjudication had been given the royal assent in a letter from Lord Sydney, the principal secretary of state at Whitehall, dated 26 June 1787. Nevertheless, because of the bitter complaints of the Bay settlers to the British establishment, charging him with ‘the grossest injustice, tyranny and oppression’, he was relieved of his duties as superintendent and recalled to London in 1790. During his time in the West Indies he had married a black woman, Catherine, with whom he had a son. He brought them back to England with him on his recall.

The Baymen kept bombarding the Home Office with slurs against Despard, but his vindication was delayed time and again. Legal writs were received from American vessels that he had impounded. His salary had been halved and expenses incurred at the Bay had still not been settled. He had been obliged to hire lawyers to defend himself and by 1791 he was in dire financial straits.

Charges against him were finally dismissed in 1792 after two years’ constant attendance upon all departments of government. Unable to meet his bills, he was sent to the King’s Bench debtors’ prison in Southwark, which could be described as a ‘gentleman’s prison’. His wife, Catherine, could visit him daily and the regime was quite relaxed.

LONDON CORRESPONDING SOCIETY

The lawsuit petered out and he was released from the King’s Bench in 1794, but the British government refused to employ him any further. Politics, which had been of no interest to him up to then, was now a motivating factor in his life (to seek justice for himself and his fellow man). He decided to join the London Corresponding Society, which had a strong Irish influence, and become a full-time revolutionary.

As the eighteenth century came to a close, revolution was in the air. The French Revolution and its aftermath and the scale of the Irish rebellion of 1798 rocked the British establishment. A short time before the Irish rebellion, Despard was accused of associating with Irish rebels and was imprisoned without trial for three years during a time when habeas corpus was suspended. His treatment in Cold Baths Prison was very harsh, and Catherine worked tirelessly on his behalf with the few friends he still retained at Westminster, especially the young independent MP Sir Francis Burdett. After his release in March 1801, Despard spent some time in Ireland and, while there, was kept aware of plans for another Irish rebellion.

A state of virtual war existed between the upper and lower levels of English society in 1802–3, with nationwide food rioting, illegal combinations (trade unions) sprouting up, an apparent revival of the United Englishmen (an offshoot of the London Corresponding Society) and the overall mischief-making of the United Irish Society. The authorities believed that they were all connected and that a French landing in Ireland would trigger another great rebellion.

LINKS WITH ROBERT EMMET?

Marianne Elliott, in her comprehensive history of the period, Partners in rebellion, writes that the general recognition of a tenuous link between the Irish rebel Robert Emmet and Despard, now heading the rebel group in London, is ‘grossly underestimated’. She defines Emmet’s rebellion as a final desperate attempt to secure Irish independence by a group of young, impatient United Irishmen who had lost faith in France, while Despard’s ‘conspiracy’ was a plot by a broken ex-colonel, driven mad by official persecution. Elliott supports her claim of the close link between the two revolutionaries by informing us that ‘Emmet’s story unfolds in London and France, for it was there, rather than in Ireland, that the rebellion was conceived and planned’.

Despard was arrested in early November 1802 with a group of suspected conspirators but, as Elliott relates, ‘the arrest produced little more than taphouse tittle-tattle from a handful of labourers and soldiers’. He was arrested again on 16 November at the Oakley Arms pub in Lambeth, south-east London, with a motley crew of English and Irish drinking buddies whom the authorities claimed were plotting to take out parliament and kill King George III. The actual plot seemed to entail more pub talk than the concoction of a practical plan, but by the time the case landed with the state security enforcers the threat posed by the conspirators had swollen to coup d’état proportions.

HIGH TREASON

In February 1803 Despard was tried for high treason. Spies had been planted amongst the group that gathered at the pub in Lambeth. One of them, Thomas Windsor, an army private, had informed a senior official that the object of the group was ‘to overturn the Government and destroy the royal family’. None of the state witnesses were cross-examined and no supporting evidence was given. Lord Nelson, the man who was later to become Britain’s greatest sea warrior, spoke glowingly of his old friend. ‘No man could have shown more zealous attachment to his Sovereign and his Country than Colonel Despard did …’ Despite Nelson’s plea, however, Despard was convicted of high treason, along with six co-conspirators. He was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered, but this grotesque ruling was commuted to a more sociably acceptable, if hardly benign, hanging and then beheading. The ‘softening’ of the decree from the King’s Bench had more to do with the fear of public reaction than with any kind-heartedness on the part of the Crown’s law enforcers.

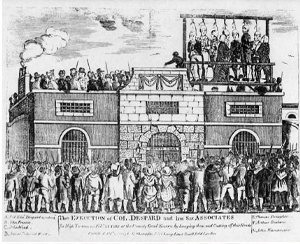

EXECUTION

On 22 February 1803 Despard was the last of the seven to be escorted up to the scaffold, which was erected on a roof newly constructed for that purpose at the entrance of Horsemonger Lane Gaol. Malcolm’s reference to Cawdor in Shakespeare’s Macbeth that ‘nothing in his life became him like the leaving of it’ could well be applied to Despard. In his final speech from the scaffold, prepared for him by his wife Catherine, he spoke eloquently of his endeavours to help the downtrodden and of his innocence of the crime for which he was convicted:

‘… though His Majesty’s Ministers know as well as I do that I am not guilty, yet they avail themselves of a legal pretext to destroy a man, because he has been a friend to truth, to liberty, and to justice [and] because he has been a friend to the poor and to the oppressed … I hope and trust, notwithstanding my fate, and the fate of those who no doubt will soon follow me, that the principles of freedom, of humanity, and of justice, will finally triumph over falsehood, tyranny and delusion, and every principle inimical to the interests of the human race.’

After the hanging, the executioner took Despard’s severed head from a person who had been engaged for the beheading and held it up by the hair in full view of the massive crowd of 20,000 onlookers. He proclaimed, ‘This is the head of the traitor Edward Marcus Despard’.

Despard’s biographer, Mike Jay, comes to the clear conclusion that the Irishman was innocent of the charges laid against him.

‘In the end, there was no real evidence linking the Colonel to Irish or French revolutionaries in a plot to overthrow King George III. Being caught in a pub surrounded by working men and soldiers carrying illegal oaths—coupled with his own radical inclinations—it seems was enough to convict him.’

Elliott agrees that there was a lack of evidence to convict. ‘All the evidence suggests he came [to the meeting at the Oakley Arms] to subdue rather than to incite … the government would have difficulty constructing a case against him without Windsor’s embellishments’.

Vincent Regan, the actor who played the part in the Poldark series, agrees with the biographer’s conclusions. He said that playing his part was interesting because Ned was a real person among the fictionalised characters in the series and that his story was about a historical miscarriage of justice.

Teddy Fennelly is a former editor of the Leinster Express and president of the Laois Heritage Society.

Further reading

M. Elliott, Partners in revolution—the United Irishmen and France (Yale, 1982).

M. Jay, The unfortunate Colonel Despard (London, 2004).

R.R. Madden, The United Irishmen, their lives and times, vol. 3 (Dublin & London, 1860).