By Thomas O’Loughlin

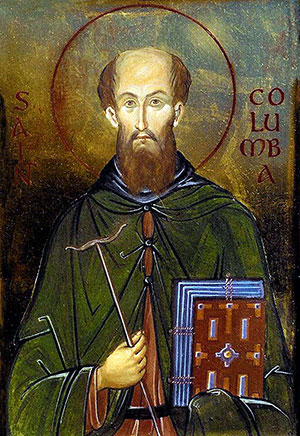

Anniversaries—including all the multiples such as centenaries—are a useful way of focusing our attention on the past and its ongoing significance for our self-understanding. And, among several other commemorations, this year has seen events to mark the 1500th anniversary of the birth of Columba (Colm Cille), the founder of the monastery of Iona, which played such an important role in the history of these islands. Culturally an outpost of Ireland, with which it remained in continuous contact, the monastery of Iona had an impact on not only Scottish but also English history, and its fame was widespread in the Latin-speaking lands through its literary products. Thus Columba, descendant of Niall Noígiallach and a Christian saint, is well worthy of an anniversary celebration this year. Moreover, his ‘life’ (written around a century after his death by his distant Uí Néill cousin, and successor as abbot, Adomnán) is as relatively accessible a text from Early Christian Ireland as one can find. It also is one of the few such texts whose popularity has given it a place in Penguin Classics (Sharpe 1995)—so many feel a warmth towards, and knowledge of, Columba as an individual.

But how much of Columba’s biography do we really know? For example, do we know that 521 is the year of his birth?

Date of death?

For any pre-modern saint, in Ireland or elsewhere, the most certain information that we have is the day of death. That said, there are many saints—recalled in early lists or even in just a place-name—of whom all we have is a name (and any other details are later ‘additions’ because someone felt that there was a need to supply more information), but if we have a name and a feast-day (i.e. the day of death) we have the core of ‘the dossier of the saint’. An example of having just this most basic information would be St Ainle on 21 June. Humans, however, hate a vacuum of information and clamour for more detail—and very often have their desires fulfilled by plausible invention.

If the saint has links to a particular place—obvious in the case of a founder of a monastery—then we have a location for the burial. With this goes the possibility of a cult—devotions—at that place, and relics. This is important because there, in the saint’s presence, in the tomb, is the site for the invocation of the saint’s protection, patronage and power. Thus we have Cronán of Ferns on 22 June: a name, a feast-day and a place—and so a cult is far more likely for Cronán than for Ainle. In the light of this, we can understand why Adomnán devotes such a lengthy description to the burial and tomb of Columba on Iona: this is a description of where the saint is now and of the place where his audience can enter into a relationship with the saint.

These annual celebrations link a name with a specific day, but links to a year, a date, are far more tenuous. Indeed, it is only in a minority of cases, usually founders of monasteries or bishops—in both cases the kinds of individuals whose deaths generate entries in annals—that we can place any value on a year of death. Columba—significant as a founder and recalled in a book-conscious community—falls into this smaller category, and so we can have great confidence that he died on 9 June 597 and was buried on Iona, and that his tomb was at the centre of his cult.

Date of birth?

What, however, of his date of birth, allowing for the fact that it was only on the basis of his later life that he came to notice? In the case of most saints (indeed, of most people in the ancient world) we need to note the presence of ‘c.’ (circa, ‘around this date’) and ‘?’ placed before the date, indicating that it is not certain. In Columba’s case we rely on incidental references. From Adomnán we find that Columba’s living until his mid-70s would fit all the evidence; this dovetails with what is found in Irish annals, which give Columba a lifespan of 75 years (although we need to make allowance for when one actually begins to be ‘75’ in an era before birthdays were significant and worth keeping in mind), while Bede in his short account of Columba in his History of the English nation as a church (Vols III and IV) says that Columba was 77 when he died (which Bede may have derived from Adomnán directly or from his own calculations based on reading Adomnán’s Vita Columbae)—the evidence was well set out by Reeves (1857, lxix). So, if Columba was roughly in his mid-70s when he died, then by subtraction from 597 we get a range of 518–523 as the date of his birth. Most opt for the mid-point, 521—hence this year’s anniversary celebrations. The key point to remember is the uncertainty of this date.

Place of birth?

Similarly, places of birth are very often later additions. The linking of Columba with Gartan, Co. Donegal, is a good example—it is first mentioned in a mid-twelfth-century homily. Hence to say simply that ‘he was born in Gartan’ is to go beyond the evidence. At best we can say: ‘Columba was born in Ireland, around 521, and, in a much later tradition, his birth is linked with Gartan, Co. Donegal’.

The rule of thumb is that the further we move outwards from a name, a feast-day and a place of burial, the more uncertain is our knowledge. Put another way, the more detail we have about dates and biography, the more likely we are to encounter later accretions based on the desire of devotees for more and more information.

Vita Columbae

But surely Adomnán’s Vita Columbae puts the case of Columba in a different light? No, because what Adomnán wrote is the ‘vita’ of a saint, intended to be used within the cult, rather than a ‘life’ in any modern biographical sense. Adomnán used a stock of standard miracle stories and structures of sanctity drawn from writers such as Athanasius (c. 296/298–2 May 373) and Gregory the Great (c. 540–12 March 604) to demonstrate that Columba fitted into an established and unquestioned pattern of holiness; to provide readings suitable for use in the liturgy commemorating the saint (and, in particular, a monastic saint); to establish Columba as an exemplar of what he, Adomnán, took to be the nature and pattern of Christian discipleship and prayer; and to show that Columba was now a powerful wonder-worker and healer for those who called on his help (the notion that he is an intercessor rather than a direct worker of miracles is a later one). The standard Latin–English edition contained a useful list of the established hagiographical works used by Adomnán as patterns (Anderson and Anderson, p. 23). Adomnán wrote to promote the cult of a saint, not to provide information suitable for modern historians interested in the sixth century.

What Adomnán wrote were ‘texts to be read’—this is the literal meaning of the Latin word legenda—at a church service in a monastery. So, to say that the stories in the Vita are ‘legends’ is only to say that Adomnán knew what he wanted to do and did it. For an introduction to the pattern, see the aptly named The legends of the saints by Delehaye.

Can we not rely on the Vita Columbae for information on Columba the man? There is a basic rule applicable to any work that claims to describe an earlier period (just as Adomnán’s work, written in the late seventh century, claims to describe the mid-sixth century): a literary work is primarily evidence for the time of its composition, and only indirectly evidence for the time it describes. This means that the Vita is evidence for how the Iona monks thought about Columba and sanctity, and only accidentally for the details on Columba himself. Moreover, we have no way of deciding which details may preserve a ‘historical’ memory and which are simply typical materials used to fill out the ‘texts to be read’/legenda. We can derive valuable generic information from the Vita about the life of the monks in a late eighth-century insular monastery on the edge of the Atlantic, but we cannot treat any story about Columba as face-value evidence for the biography of the sixth-century individual.

The various ‘lives’ (vitae) are therefore the most voluminous part of the dossier of a handful of saints, but also the least valuable part of the dossier in modern historical terms. Nevertheless, when these legenda are taken as a whole, they offer us insights into the minds and worlds of those who wrote them, the desires that underpinned their composition, and the world-view of those who valued, performed and listened to them.

Commemoration

So, should we celebrate ‘Columba 1500’ this year? As a matter of strict evidence, we should reframe it as ‘Columba, c. 1500’ to conform to his dates as c. 521–597. Memory, however, is always both a lot more and considerably less than such historical precision, and one of the tasks of the historian is to pose continually the questions: how do we know this, how accurately do we know this, and what is the nature and specific value of our evidence?

Thomas O’Loughlin is Professor Emeritus of Historical Theology at the University of Nottingham.

Further reading

A.O. Anderson & M.O. Anderson, Adomnan’s Life of Columba (Edinburgh, 1961 and 1991).

H. Delehaye, The legends of the saints (Dublin, 1998) [French original, 1905].

W. Reeves, Vita Sancti Columbae auctore Adamnano (Dublin, 1857) (https://archive.org/details/vitasancticolumb00adam).

R. Sharpe, Adomnán of Iona: Life of St Columba (London, 1995).