By James Bennett

‘There are more cricket clubs and unofficial “elevens” in Co. Dublin per square mile than in any other part of Ireland. This ancient game … is played enthusiastically on almost every village green.’

(Drogheda Independent, 19 September 1936)

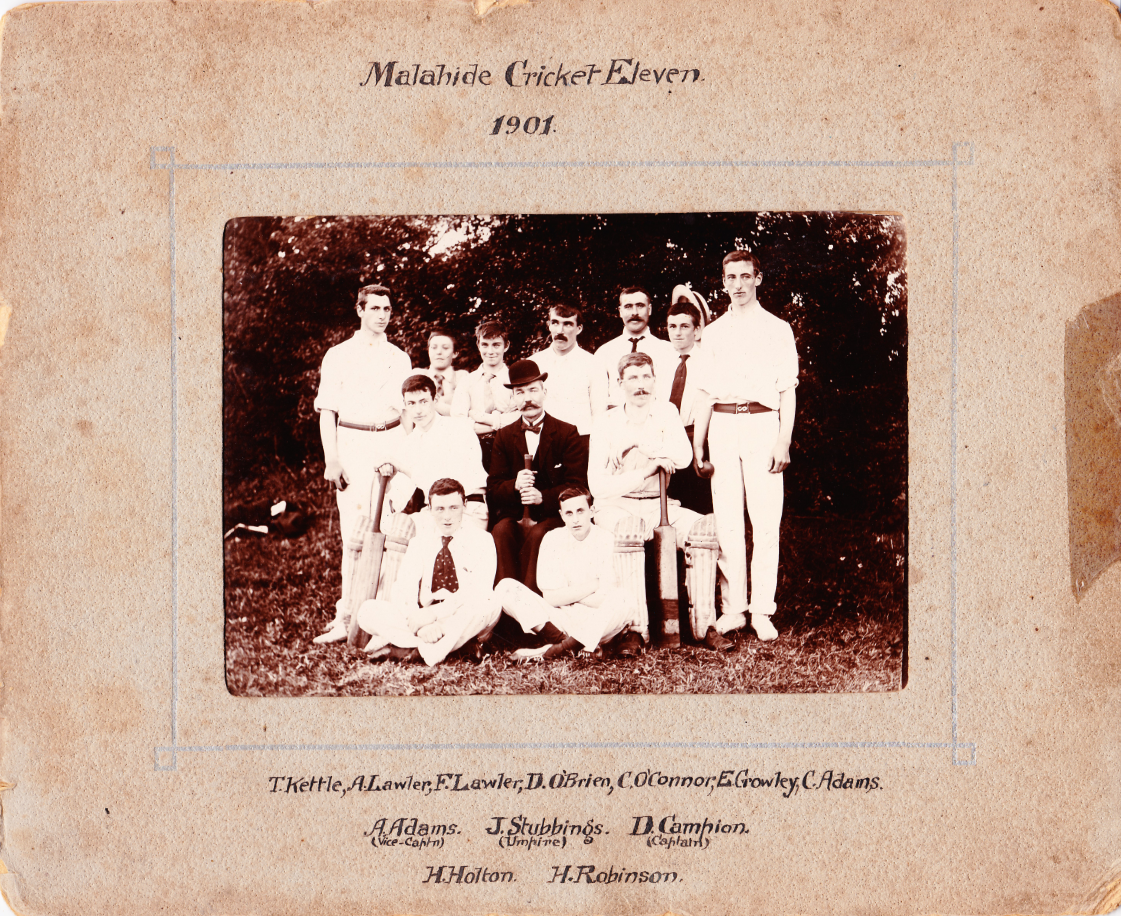

Sports historians and various commentators have provided many reasons for cricket’s decline from a mainstream sport in Ireland in the 1870s to a minority sport by the early twentieth century. One of the consequences of the Land War of the early 1880s was to drive a further wedge into the already difficult relationship between landlords and tenants, with the result that landlords were not inclined to engage in sporting activities with their tenants when outrages were occurring on a regular basis. The founding of the GAA in 1884 meant that cricket now had a competitor for playing fields and for players. Things became even more difficult between 1901 and 1910 when the GAA banned its members from playing or watching cricket, hockey, soccer and rugby. The Gaelic Revival of the early 1890s, with its emphasis on all things Irish, provided plenty of scope for those who regarded cricket as the most quintessentially English of all field sports. While a confluence of all or some of these factors contributed to the demise of cricket as a mainstream sport, it has been argued by Paul Rouse that the preference for ‘social cricket’ and the failure of cricket-lovers to put organisational structures in place to regulate the sport during the 1870s and 1880s were also factors. He accepted, however, that the complexities of life in rural Ireland meant that different factors were at work in different areas, and that undoubtedly was the case towards the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, when cricket was thriving in Fingal.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN FINGAL AND THE REST OF IRELAND

While there were large landed estates in Fingal such as Holmpatrick in Skerries and Talbot in Malahide, the pattern of land ownership in Fingal differed from the rest of Ireland. Thanks to the various land acts, many of the tenant farmers were enabled to buy out their holdings, with the result that there was not the same level of dependence on the gentry for the promotion of cricket. The farmers who were able to give access to a playing field for cricket couldn’t be without the field for the whole season, so the only fields that could be given over were ones used for grazing purposes. A field grazed by sheep was preferable because the grass tended to be shorter. It was also easier to clear away the excrement, one of the first jobs on the day of a game.

One of the factors in the relationship between landlords and tenants in Fingal was the lack of residual bitterness from the Great Famine; indeed, local tradition has it that no one on the Woods estates (Milverton Hall, Whitestown or Winter Lodge) died as a result of the Famine. At Milverton, George Woods slaughtered a bullock once a week to ensure that his employees were fed, and he also employed large numbers on drainage and land reclamation schemes. While it is not being suggested that Fingal was an egalitarian utopia and that relationships between landowners and tenants and farm labourers were always harmonious, in general it appears that there was a level of tolerant co-existence. Cricket was an area of activity where there was a connection between the landlords and their tenants, although it was reported that at some games the former took their refreshments in different quarters from their workers.

The GAA’s ‘ban’ was ignored in Fingal not from a lack of patriotism but owing to pragmatism, because GAA clubs would not have been able to field teams if the players of ‘foreign’ games were banned. Among the outstanding sportsmen who played Gaelic games and cricket were Bobby Beggs (winner of All-Ireland football medals with Dublin and Galway), Paddy Neville (hockey and cricket international, goalkeeper with Drumcondra AFC and midfielder with Parnells GAA club), Con Martin (soccer international) and Peter P. O’Brien (man of many cricket clubs, outstanding athlete and handballer).

The availability of the rail network was of crucial importance because it provided flexibility and choice in terms of fixtures for teams, and it is no coincidence that clubs were founded in Malahide, Skerries, Balbriggan and Rush. Another factor was the involvement in cricket of the visitors to Skerries and Rush who rented houses during the summer. The Holmpatrick cricket team was comprised of members of the sizeable Anglican population in Skerries, summer residents and visitors to the area. Balbriggan had developed as a major manufacturing centre with the result that there was a constant influx of migrant workers from England, Scotland and Wales..

On the evidence of the reports in the local newspapers, there were at least 23 cricket clubs in Fingal between 1897 and 1910. Many of these could more correctly be called teams because they were simply groups of like-minded individuals who came together to play cricket and had been given access to a field by a friendly landowner. The fields that were used could change from season to season, or even during a season, and finding a field in which to play was a constant problem.

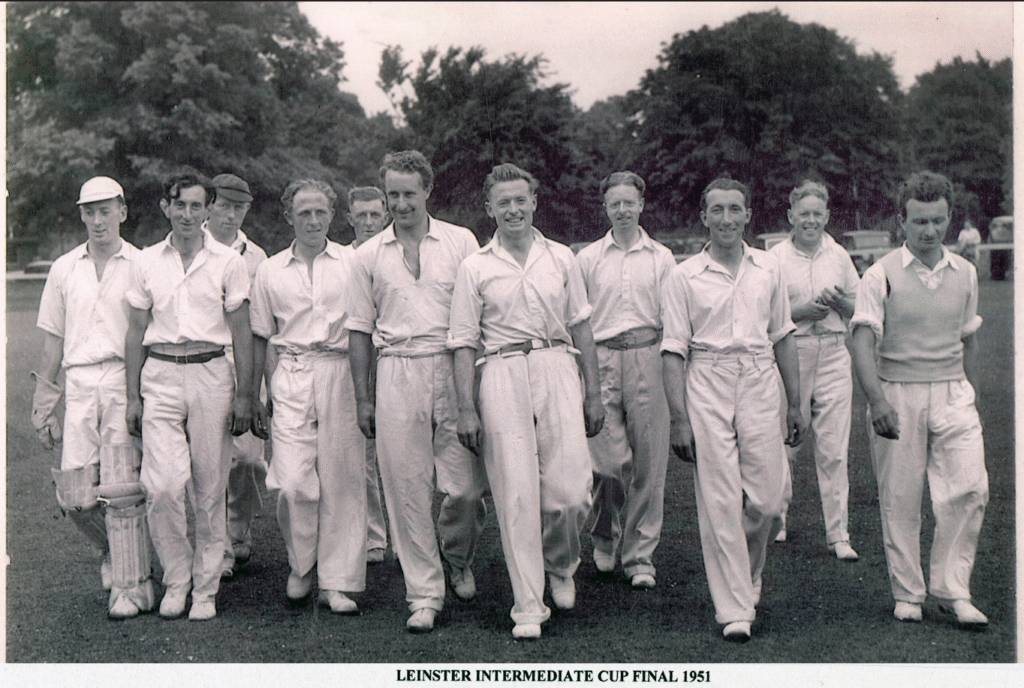

Local, national and international events were predominant during the next fifteen years or so, with minimal attention being given to the reporting of cricket. The farm labourers’ strike, the Great War, the 1916 Rising, the War of Independence and the Civil War caused attitudes to harden regarding anything to do with England. Politically and socially, it was not expedient to be involved in cricket during troubled times, but the regard for cricket in Fingal ran very deep and Fingallians were traditionally ‘possessed of an independent spirit’. They did not appreciate being dictated to by cultural nationalists or others regarding the games that they might or might not play. The rebirth of cricket in Fingal commenced in 1925 with the reorganisation of Skerries and Knockbrack cricket clubs, and the announcement in October 1926 that north County Dublin cricket clubs intended to form a league and were confident of having it ‘in full working order before the opening of the next season’. Having taken all other circumstances into account, the greatest single factor in the preservation of cricket in Fingal was the establishment of the Fingal Cricket League.

FINGAL CRICKET LEAGUE, 1927–31

In 1926 there were cricket teams in Balbriggan, Ring Commons, Knightstown, Skerries and Knockbrack, but fixtures for the most part were still being arranged as challenges rather than there being any official structures in place. A Fingal Cricket League committee was formed, and it met in Ring Commons schoolhouse on 13 March 1927. The teams that competed in 1927 were Skerries, Knockbrack, Macraidh (Knockbrack II), Ballymadun, Knightstown, Black Hills and Ring Commons. The first fixtures were played on Sunday 15 May 1927 and the final between Skerries and Knockbrack, which Skerries won, was played on 18 September 1927.

By 1929 the number of teams had increased to fifteen. There were no defections from the previous year and the new teams were Balbriggan, Naul Hill, Skerries B, Balcunnin and Curkeen. The league was divided into two sections, and by the end of the season most of the teams in Division A had played twelve games and the teams in Division B had played fourteen games. Skerries’ reign as champions was ended when they lost the semi-final to Knockbrack, who only scored 14 runs, with Ennis (6) being the only one to make anything worthwhile, but Skerries were dismissed for 13 runs, and Knockbrack went on to beat Baldwinstown in the final on a score of 24 runs to 16..

At the AGM in 1930 there was a wave of optimism, with representatives of 25 clubs present—which, if it had translated into teams entered in the Fingal League, would have constituted an increase of ten teams in comparison with the previous season. The new teams were Portrane Psychiatric Hospital, the British Legion and Man-o’-War. Balcunnin and Knockbrack contested the 1930 final and the official score was 40 runs each, but the Drogheda Independent’s correspondent, and at least another hundred people in the ground, had the score at 41 to Knockbrack and 40 to Balcunnin. The marker’s decision was final, however, and the replay was fixed for the following Sunday..

The replay also took place at Balbriggan and, in typical Fingal fashion, the bowlers were on top. Knockbrack batted first and lost the first four wickets for 7 runs. The final score for Knockbrack was 23 runs, with Johnny Murphy taking six wickets and Simon Hoare taking four. Nine Balcunnin wickets fell for 14 runs but the last pair, Tommy Power and John Hoare, brought the score to 22, when Jem Murphy took a miraculous one-handed catch off his own bowling to leave Knockbrack II the winners by one run and with the honour of being the first team to have its name inscribed on the Fingal Challenge Cup.

POSTSCRIPT

By the first decade of the 21st century Fingal was being referred to as the ‘heartland of Irish cricket’. North County Cricket Club’s first XI was by a very considerable distance the strongest cricket team in Ireland, having won the Irish Senior Cup on five occasions between 2001 and 2008. In addition to having a brilliant first XI, the club, which was based at Inch, Balrothery, had built a centre of excellence, which has become the benchmark for all subsequent such centres. The Ireland cricket team, which performed so well at the World Cup in 2007, had three of its players (Andre Botha, Paul Mooney and John Mooney) on the panel, and Matt Dwyer from the Hills Cricket Club was the assistant coach. The England team that won the World Cup in 2019 was captained by Eoin Morgan, a fourth-generation Fingal Cricket League player.

The Fingal Cricket League continued until 2012, but by then had served its purpose in achieving the survival of cricket in Fingal. The subsequent cricketing successes owed much to the officers of the League, who ensured that cricket has continued to make an outstanding contribution to the sporting and cultural identity of Fingal.

James Bennett was president of Cricket Leinster in 2022.

Further reading

J. Bennett, The story of cricket in Fingal (Dublin, 2022).

P. Bracken, Foreign and fantastic field sports: cricket in Tipperary (Kilkenny, 2004).