By Joseph E.A. Connell Jr

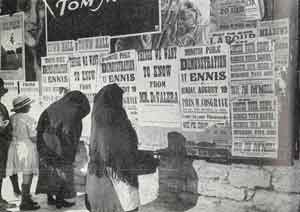

The 1923 general election was held on Monday 27 August and was the first since the adoption of the Irish Free State constitution on 6 December 1922. It was contested under the Electoral Act (1923), which increased the number of seats in the Dáil from 128 to 153. Lax electoral practices were tightened up beforehand by the Prevention of Electoral Abuses Act (1923).

The election was won by the Cumann na nGaedheal party, which won 63 seats, with 39% of first-preference votes cast. On 19 September the governor-general, Tim Healy, appointed W.T. Cosgrave as the new president of the Executive Council, the cabinet and de facto executive branch of government. Formally, its role was to ‘aid and advise’ the governor-general, who would exercise the executive authority on behalf of the king. In practice, however, it was the Executive Council that governed. Until 1932, Cumann na nGaedheal continued to form the government of the Irish Free State, with Cosgrave as president of the Executive Council.

The pro-Treaty wing of Sinn Féin had decided to break off and become a distinct party, Cumann na nGaedheal, in late December 1922, but its launch was delayed until after the New Year as a direct consequence of the turmoil caused by the Irish Civil War. Sinn Féin candidates, many of whom were in prison and none of whom entered the Dáil, won 27% of the first-preference votes.

Cumann na nGaedheal was actually the second party of that name (the first was in 1900) and did not come into existence until more than a year after the split with Sinn Féin on 27 April 1923, when the pro-Treaty TDs recognised the need for a party organisation to win elections. The party was largely centre-right in outlook. In government, it established the institutions upon which the current Irish state still rests. It re-established law and order through a number of public safety acts in a country that had long been divided by war and competing ideologies. The party’s minister for home affairs, Kevin O’Higgins, established An Garda Síochána, an unarmed police force. Later, as minister for external affairs in 1927, he was successful in increasing the Free State’s autonomy within the British Commonwealth of Nations.

Cumann na nGaedheal in government was characterised by conservatism. Thus, when J.J. Walsh, minister for posts and telegraphs, resigned in 1927 owing to the government’s lack of support for protectionism, he sent an open letter to Cosgrave, claiming inter alia that the party had gone ‘over to the most reactionary elements of the state’. Addressing the Dáil, O’Higgins once said: ‘I think that we were probably the most conservative-minded revolutionaries that ever put through a successful revolution’.

Todd Andrews commented on the times when he described the men of his local Sinn Féin club in Rathfarnham as being

‘… astonishingly conservative. It might be expected that men who were prepared to support a rebellion against the political status quo would have shown some liberality of view but social questions—such as housing, public health, education—were seldom mentioned.’

Support for Cumann na nGaedheal gradually declined with the establishment of Fianna Fáil in 1926. Cosgrave’s party became solely identified with protecting the Treaty and defending the new state, while it seemed preoccupied with public safety. Economically the party favoured balanced budgets and free trade at a time when its opponents advocated protectionism. The weak economy of the Free State suffered during the Great Depression, and the stage was set for Fianna Fáil’s victory in 1932.

Joseph E.A. Connell Jr is the author of The Terror War: the uncomfortable realities of the Irish War of Independence (Eastwood Books).