Written, produced and presented by Patricia Baker Newstalk, 20 August 2023

By Sylvie Kleinman

Every monument will eventually come down. They are, by their very nature, antagonistic. This documentary is a thought-provoking stroll through Dublin by Patricia Baker, who explores monuments, specifically statues. Some of the controversies they engender, and what and how we choose to commemorate in the future, are themes flagged—though, from a historical narrative perspective, not satisfactorily developed. The stroll considers whether they are still standing, blown up, partially reconfigured, taken down or even transported abroad. Academic historians, art historians and arts practitioners reflect along with Baker. The programme is clearly driven by new thinking on visual and material culture inspired by external influences, most obviously the Black Lives Matter movement. The iconic, iconoclastic and impulsive removal and dumping of Coulson in Bristol led to a creative aftermath. The Shelbourne Four débâcle around the Nubian female statues is recalled: they appear subjugated, if not enslaved. A lot still needs to be done about the ‘decolonisation’ of our public sculptures and monuments. In a museum, for example, the hotel’s statues could form a curated exhibition elaborating on the values of the society that created them, giving them a context. As cultural artefacts, they should not be destroyed but should channel education. Though we are ‘in the middle of a controversial debate’, the de-naming of the Berkeley Library in Trinity College, to date Ireland’s landmark statement, is not mentioned.

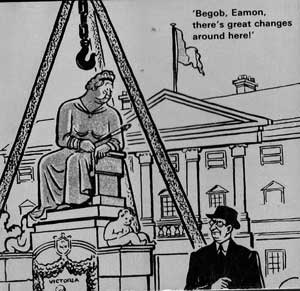

Removal creates a gap in our connection with the capital’s past. George I once gazed down at Essex Bridge, and very few passers-by are probably aware of the ultimate removal of a grandiose 1908 monument to Queen Victoria from the plinth of Leinster House in 1948. Cartoonists at the time could not resist the temptation to lampoon the vertical hoisting of the voluminous queen, with Dev surveying the scene. Evidently the Nelson’s Pillar to Spire, the ‘syringe in the dinge’, débâcle is considered. Many lost the site by which to remember a first date, as the pillar was a meeting point, or the adventure of climbing up to view Dublin. This overshadowed any considerations about our oppressed imperial past. Quite a lively post-event narrative evolved, however, with rich possibilities for material and visual culture. As Irish TV was in its infancy, the actual media coverage of the formal army explosion created a national shared experience and an archive. Two pop songs commemorated the event, and the Spire’s neutral blandness could be regenerated with some sort of narrative installation.

While on O’Connell Street, we hear that its parade of statues is fascinating, or now irrelevant to passers-by. The valid point is made that by elevating one particular figure—e.g. elsewhere Mandela—one skews the narrative of a particular chapter of history led by other freedom fighters too. Virtually all the examples in this programme are nineteenth-century, yet no one flags heroisation in the romanticised history of the age, a theme thoroughly deconstructed in other countries. It is hinted at when the statue as public education, a great white man to emulate, is discussed, but the view seems to be that their meaning is lost to the ‘new Irish’ in our increasingly racially diverse and multicultural society. Really? In Daniel O’Connell we have the leading Irish voice in the British campaign to abolish slavery, a fact highly relevant today, if absent when it was unveiled in 1882. It was he who originally demanded the publication of slave-owner information, which became the compensation database that continues to inform a wide range of actions and practices in the UK in recent years.

The statue of another former jailbird, William Smith O’Brien, was erected in 1870 (originally on D’Olier Street), i.e. before Grattan (1876) and the Liberator. Represented as a Victorian gent in civvies, he may appear too nerdy for contemporary aesthetic tastes, but is Smith O’Brien not our first nationalist, and a rebel to boot, to be ‘statufied’ in Dublin? That sort of question is framed in other countries when considering shifts in power dynamics and civic monument policies. Remembering ordinary people is called for, and gender is finally raised, if only at the end. Constance Markievicz is obviously mentioned, but not her neatly buttoned Irish Citizen Army tunic on her bust in St Stephen’s Green. Is this not the only glimpse we get of an Irish revolutionary in uniform? British martial glory is mentioned, but not an Irish equivalent. At ‘Tonehenge’, we only hear of the otherwise interesting history of the original foundation stone, carved out of Cave Hill in Belfast, and its laying during the highly orchestrated events in 1898. But that’s it. Not a shred of regret that Tone (like Thomas Davis) is dehumanised in that neutralisation of his genuine appearance, obviously driven by the burden of the 1960s/70s art trends of the day and the age’s negativity.

One solution, e.g. in the former Soviet bloc, is to create statue graveyards in the suburbs. In fact, the documentary ends on Dublin’s periphery, with John Byrne’s innovative Misneach (2010) in Ballymun. Symbolising local youth and the possibility to achieve, it depicts a young local woman in a tracksuit riding bareback on a horse. The latter was moulded from the remains of Viscount Hugh Gough’s statue, blown up in 1957. Playfully it connects a conventional equestrian statue with the local horse-riding tradition, gently subverting its British imperial origins.

In many ways the audio format is ideal, encouraging us to focus our aural attention and conjure up the choices discussed. Inevitably there is some extraneous street noise, though the tram ‘ding ding’ projects the urban landscape well, but sometimes we struggle to grasp incisive comments, competing with the unnecessarily loud and clangy synthesised mood music. What remains and what should be removed was, apparently, already a conversation back in Roman times. Arguments remain open-minded, no categorical solutions are formulated, and Dead White Men opens up many valid conversations.

Sylvie Kleinman is Visiting Research Fellow at the Department of History, Trinity College.