By Michael Quinn

In 1961 Desmond Greaves (1913–88), the London-based leading light in the Connolly Association (CA) and editor of its monthly newspaper, the Irish Democrat, published his seminal biography The life and times of James Connolly. The book was greeted in Ireland and Britain as a landmark publication in the canon of labour movement literature, but there was no question of Greaves resting on any Connolly laurels. The CA—founded in 1938 to represent the interests of Irish exiles in Britain, to promote the ideals of James Connolly and to campaign for a united and independent Ireland—was focused on ending partition and exposing the unionist monolith in Northern Ireland. The political context included the petering out of the IRA’s border campaign (1956–62) and the recent release of all internees from Crumlin Road Gaol. The latter was hastened in no small measure by the CA’s success in getting over half of the British Parliamentary Labour Party to sign a telegram of protest to Prime Minister Brookeborough at Stormont. This boosted the CA’s ability to use its influence within the labour movement to bring pressure to bear on Harold Macmillan’s Conservative government. Greaves had already exposed the fallacy that the House of Commons could not interfere in the North’s internal affairs by highlighting that Section 75 of the Government of Ireland Act reserved to Westminster supremacy over the six counties.

NUCLEAR DISARMAMENT

Also topical in the Cold War context was a popular demand for nuclear disarmament. This was shown by the rise of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), whose march from the nuclear bomb factory at Aldermaston to Trafalgar Square in London attracted 100,000 supporters in 1960. Indicative of a rising radical youth culture, 40% of CND marchers were under the age of 21.

The CA, which was experiencing an influx of young Irish immigrants into its own ranks, decided on a march from London to Birmingham. Five demands were set out in the Irish Democrat:

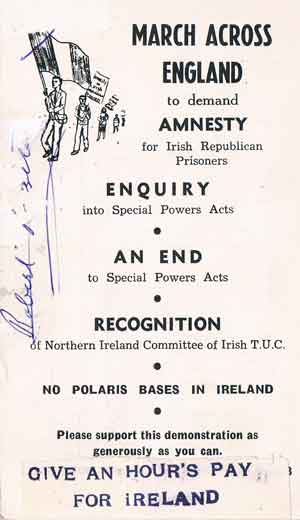

- Repeal of the Special Powers Act, under which suspects could be imprisoned without charge and the RUC could enter homes and make arrests without warrant.

- Release of convicted republican prisoners.

- Recognition by Stormont of the Northern Ireland committee of the Irish Congress of Trade Unions (ICTU).

- A public enquiry into allegations of discrimination against Catholics.

- Scrapping of Lord Brookeborough’s offer to accept submarine bases in the North for the US–British Polaris ballistic missile system.

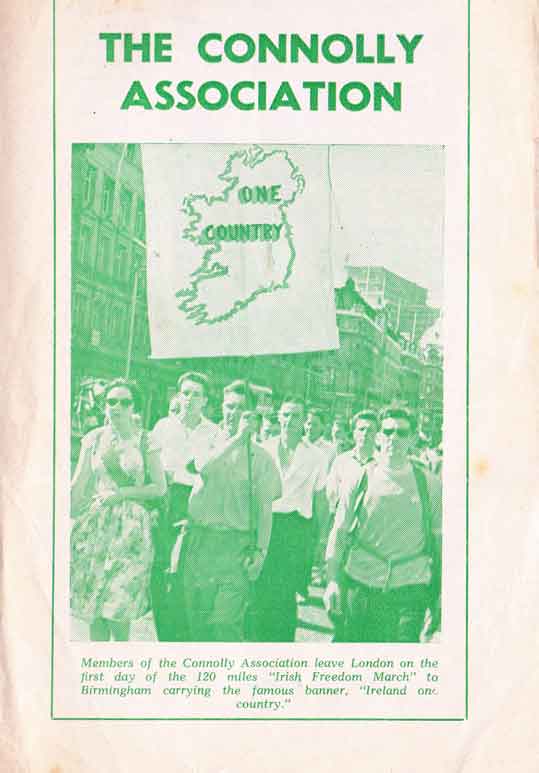

Following a rally in Trafalgar Square on 25 June 1961, which was addressed by Ben Parkin, Labour MP for Paddington, a dozen marchers set off for the week-long trek to Birmingham. Some had given up a week of their fortnight’s annual leave to participate. They carried a banner emblazoned with a map of their homeland and the words ‘One Country’. They were piped as far as Cricklewood by Leitrim man and member of the London Pipe Band Larry O’Dowd. The itinerary, prepared by the CA’s organiser, Cork man Anthony Coughlan, included stops in St Albans, Luton, Bedford, Northampton, Rugby, Coventry and Birmingham. Local committees made up of labour movement and CND volunteers met the marchers outside these towns. They marched with them to meetings at public squares and factory gates—and provided beds for the night. Extra momentum was added when it emerged that during the recent Belfast municipal election Unionist candidates and employers Armstrong, Armstrong and Henry boasted in a leaflet that they had never employed a Roman Catholic. In Luton, in spite of a heavy police presence, 250 gathered to support them outside the Vauxhall car factory. In Bedford Tom Redmond, a Dubliner, addressed a crowd as the thermometer reached 32° Celsius. Eight miles out of Northampton, in the blistering heat, a local CA member, Seán MacDomhnaill, drew up in a car with a dozen bottles of ice-cold milk. In the town an enthusiastic gathering lingered with them on the street until after nightfall. En route to Rugby they passed through rolling parkland where aristocrats with names familiar in Ireland still owned estates: Graftons, Spencers, Lansdownes. In Rugby they held discussions with shop stewards in the British Thompson-Houston engineering company, and with local Labour leaders. But the last leg brought torrential rains and flooded roads, and they arrived in Birmingham footsore and wet through.

SECOND MARCH, AUGUST 1961, LIVERPOOL TO NOTTINGHAM

Ten men and four women participated in the 165-mile circuit from Merseyside that took in Warrington, Manchester, Oldham, Huddersfield, Halifax, Bradford, Leeds, Wakefield, Chesterfield, Mansfield and Nottingham. Anthony Coughlan again organised the logistics and marched the first half of the route before departing to take up a lecturing position in social policy at Trinity College, Dublin. He was appointed Dublin correspondent of the Irish Democrat, and Seán Redmond, an older brother of Tom, was appointed as the CA’s full-time general secretary. The marchers again met with an enthusiastic response, especially in Lancashire, but they had to contend with efforts from two quarters to work up prejudice against them. First, William Douglas, secretary of the Ulster Unionist Council in Belfast, had written letters to Yorkshire newspapers denouncing the march before it arrived, claiming that the Special Powers Act was justified. Even so, in Wakefield, where the Trades Council had circularised affiliated organisations, the marchers addressed the first outdoor meeting of labour movement activists since the war. They were further heartened to see in the crowd a man wearing a fáinne—an ex-internee. It was at the gates of Moston cemetery in Manchester, after a 25-mile march to honour the veteran Fenian Seamus Barrett, that they were blocked by fellow Irishmen. Barrett’s grave was the property of the local Gaelic League and they refused the CA permission to place a wreath on it. When the marchers stood their ground, a Brother John was called to the scene. With a judicious use of clerical clout, Brother John smoothed the way for the wreath to be laid. The Irish Democrat acknowledged Brother John’s tact and derided their would-be obstructors: ‘We are being slandered because of the hatred of some and the jealousy of others. But we know well we are being slandered because we are doing something.’ When the contingent reached Nottingham, they were rewarded with their best-supported event—about 500 were present.

PUBLICITY

The marches attracted press coverage ranging from Cork city’s Evening Echo to the mainstream British Sunday People. The People focused on a telegram sent by twelve English Protestant clergymen to Lord Brookeborough to protest against the blatant sectarianism in the above-mentioned Belfast Unionists’ election leaflet. Brookeborough’s reaction was to dismiss the telegram as it had been sponsored by a ‘communist organisation’. By refusing to distance himself from the leaflet, he was exposed to the scornful logic of the People’s columnist: ‘Any God-fearing churchman is now branded a communist’.

Many regional English newspapers carried news of the marchers and their cause. Typical was a Halifax Daily Courier report, which featured a photo and a comment from Greaves:

‘We are endeavouring in the main to draw attention to the existing political conditions in Northern Ireland. We want the same civil liberties that exist in England. Habeas corpus and recognition of the trade union movement.’

Moreover, under a front-page headline ‘John Bull’s other [Salazar’s] Portugal’, the New Statesman accepted that Britain was shoring up a regime in its own backyard wherein elections were a mockery of freedom and the RUC exercised draconian powers. Greaves, noting that the New Statesman was favoured by the leadership of the Labour Party, remarked that ‘The crack is becoming a breach’.

GREAVES’S INVESTIGATION TEAM IN NORTHERN IRELAND

When the IRA announced in February 1962 that it was ending its border campaign, the CA welcomed the decision as ‘sensible and realistic’. They seized the day by announcing a third march, but Greaves recognised that more research into the facts on the ground in the North would first be needed in order to further expose the wounded Brookeborough. He had already developed contacts with the republican Seán Caughey, who was running a civil liberties committee in Belfast, the veteran Nationalist Party leader and MP for South Fermanagh Cahir Healy and Canon Tom Maguire, the outspoken Catholic parish priest of Newtownbutler. In September 1961 the Irish Democrat carried an open letter from the canon to Lord Brookeborough. He recalled that as a young curate he had worked closely with Lady Brooke, the prime minister’s late mother, who had helped to promote a crochet industry to employ the Catholic poor of the parish of Brookeborough—in contrast to her son’s infamous outburst to the Orange Order: ‘Catholics are traitors. Employ none of them. I have not one about my house.’

Greaves, along with Seán and Tom Redmond and Anthony Coughlan, conducted a ten-day investigation across the North and published their findings in the Irish Democrat, of which the following is but a flavour. In Enniskillen Greaves witnessed the worst housing conditions he had ever seen—worse than in the slums of Liverpool, London, Dublin or Glasgow. Further, in this predominantly nationalist area, of the total of 192 houses built by the Enniskillen Rural Council since the foundation of the North, 146 had been let to Protestants. In Derry city, where voter rolls showed that there were 13,165 Catholics and only 9,117 Protestants, the local council was made up of twelve Unionists and only eight Nationalists. A study of the records of the council’s employees revealed that the best jobs were the preserve of Protestants.

THIRD MARCH, APRIL 1962, LIVERPOOL TO LONDON

While the marchers again carried the ‘Irish freedom’ banner, the main theme on their placards was ‘Human rights in the Six Counties’. They embarked on the 260-mile, fourteen-day marathon on a cold, dreary morning, but as it was Aintree Grand National day the occasion was enlivened by a few jokes. Perhaps there were quips about them being ‘stayers’ for the long haul until they reached the winners’ enclosure at Hyde Park? They were certainly demanding the political equivalent of a steward’s enquiry, for they brought with them signature sheets for a public memorial, addressed to the home secretary, seeking an investigation into the North.

The meeting in Manchester, hosted by the local Trades Council, was doubly encouraging for the marchers. They received support from a range of Manchester working-class organisations and were addressed by Betty Sinclair, secretary of the Belfast Trades Council. She had flown over specially to denounce Unionist plans to hype the 50th anniversary of the Ulster Covenant of 1912 ahead of the coming general election. Promoted by Edward Carson and James Craig, the covenant had been the centre-piece of defiance against a Home Rule bill enacted by the British parliament. Sinclair, who hailed from Protestant east Belfast but was a doughty opponent of unionism, lambasted this triumphalist attempt to divide the workers, Catholic and Protestant. ‘It is’, she declared, an attempt to ‘have returned for every seat [in Stormont], representatives of the employing class, the landlords and the moneylenders’.

Regional newspapers recorded the contingent’s progress through the Midlands. The Sentinel of the Potteries featured on its front page a photo of them garbed in oilskins and fishing hats at Hanley, while the Express and Star of Wolverhampton captured Greaves with the Redmond brothers checking the route on a map at Stafford. Both papers noted the purpose of the march: ‘to draw attention to the disparity between the human rights enjoyed in Northern Ireland and those enjoyed in Great Britain, to the disadvantage of the former’.

When at last they reached Shepherd’s Bush, piper Larry O’Dowd and a gathering of CA members and supporters welcomed back the weary wayfarers and led them to Hyde Park for a final meeting. They were greeted by the president of the CA, Belfastman Joe Deighan, who had come from Manchester to speak.

EPILOGUE

Were the marches a success? Seán Redmond wrote that thousands of people saw their banners and posters and many more heard their case at public meetings. Press coverage ensured that hundreds of thousands read about their cause. He concluded: ‘At times it was hard going. But we are all determined, if necessary, to do it again, and again, and again.’ Greaves made a more pragmatic assessment: ‘We had a good reception but people found it hard to visualise the conditions we were describing’. By the mid-1960s he had published a series of pamphlets on the North aimed at influencing British public opinion and political leaders; he organised high-level contacts between Labour MPs, nationalist politicians and emerging civil rights activists; he helped put the Irish question and Irish votes on the agenda ahead of the 1964 general election, which ushered in Harold Wilson’s Labour Party after almost two decades of unbroken Tory rule; and, with his encouragement, in 1965 Betty Sinclair’s Belfast Trades Council convened a conference to deliberate on how ‘to obtain civil, religious, social and political rights for all in Northern Ireland’. By dint of such initiatives it can be seen that Greaves was the progenitor of the concept of the civil rights movement and that the CA’s gallant marches across England were effectively the first marches for civil rights in Northern Ireland.

Michael Quinn is currently working on a biography of Desmond Greaves, with support from Professor Emeritus Anthony Coughlan, Greaves’s literary executor.

Further reading

D. Greaves, Reminiscences of the Connolly Association (London, 1978).