Doctus in se semper divitas habet.

(School motto: ‘The learned man always has riches within himself’.)

By Michael Quinn

Charles Desmond Greaves, the historian, poet, scientist, philosophical thinker and political activist who dedicated the greater part of his life to Irish affairs, was born in 1913 in Birkenhead on the Wirral Peninsula, across the River Mersey from Liverpool. In the 1940s he became secretary of the Connolly Association, London, and editor of its monthly newspaper, the Irish Democrat. He is best known in this country for his biographies of James Connolly (1961), Liam Mellows (1971) and Seán O’Casey (1979), and for his history of the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (1982). He is also remembered for pioneering from the 1950s the concept of a campaign for civil rights in Northern Ireland to undermine unionist majoritarianism at Stormont, which proved to be a significant influence on the civil rights movement of the 1960s. In the 1970s he opposed British and Irish membership of the Common Market, from a left-wing perspective. The Desmond Greaves Annual Summer School has been held in Dublin since his death in 1988 to highlight his legacy and provide a forum for political thought and discussion.

Greaves’s forebears were of English, Welsh and Irish backgrounds. His father, Charles, was an overseer in Liverpool Post Office and his mother, Amy Elizabeth, had a degree in music. His only sibling, Phyllis, was born in 1916 when her father was on service as a sapper with the Royal Engineers in France during the First World War. The Greaves, who lived at 7a Rockville Street, Rock Ferry, were orthodox Methodists. Both parents played leading roles in the choir of their local church. His mother taught him to play piano to a high standard and fostered his lifelong appreciation of classical music.

Birkenhead Institute

Greaves’s secondary education began in 1925 when he enrolled in the Wirral’s most prestigious schools for boys, the Birkenhead Institute. This had been opened in 1889 by a group of influential citizens of Birkenhead at a time when some 400 children were crossing the Mersey daily to attend Liverpool schools. According to the school’s official history, the founders were determined to ‘establish a Public High School in Birkenhead to provide a first-class Mercantile and Collegiate education for boys on terms not exceeding those charged at the best public schools in Liverpool’. Among the school’s benefactors was Henry Tate, one of Liverpool’s most prominent sugar merchants and founder of the Tate Gallery, London.

Accounts of Greaves’s standout achievements are to be found in the school’s magazine, The Visor, with the first mention occurring at Easter 1928, when he won third prize in his form’s exams. He features more prominently in the next edition, with what was his first piece of work to be published: a sonnet. Neatly constructed, properly rhymed yet charmingly tongue-in-cheek, it is dedicated to a pastime to which his peers could readily relate:

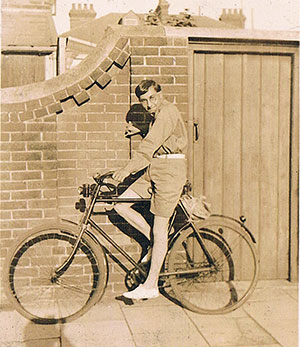

A bicycle

Two wheels—five bars—pedals—a brake,

The thing my horror doth awake;

Endowed with unique jolting powers

To charm away the leisure hours.

Squeaking—like that of heavenly lyres,

And—most of all—pneumatic tyres.

But this is no imagined ill,

The road is everywhere up hill;

It does not set you at your ease

To battle with contrary breeze;

And it upsets the normal mind

To face with tears the winterly wind,

And lastly, yet by no means least,

Your face is made mosquitoes’ feast.

The poem may have been inspired by his first long-range cycle ride, which he undertook on 2 September 1927 into north Wales—a round trip of 88 miles through the towns of Ruthin, Corwen, Llangolen, Wrexham and Chester.

Chess

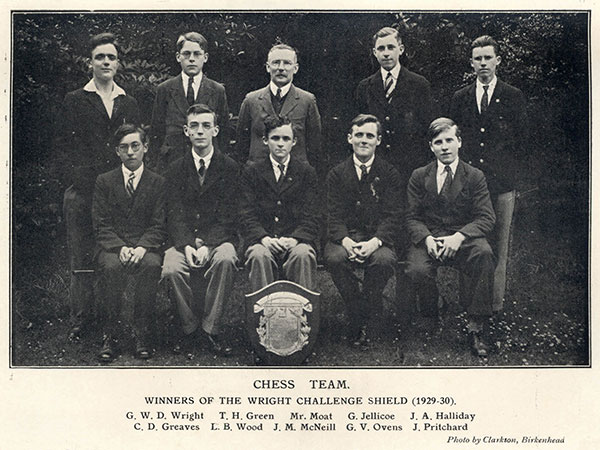

Greaves became a member of the school’s chess club. As regular winners of the Wright Challenge Shield Competition for schools across the wider Liverpool region, the club was held in high regard by staff and pupils alike. It was under the guidance of the school’s teacher of French, Charles Moat, of whom the official history seems to hint at a fearsome side, saying that he ‘made an impression both physical and mental’ on those pupils who dared to absent themselves from their French lessons. Greaves avoided the extremes of Moat’s disciplinarianism, as much for his ability at the chessboard as for French lessons, which he later recorded in his personal journal:

‘He ran the school chess club in which I was very active and in my student days used to go to his house for a game. He had some colourful expletives for pupils who did not come up to standard. “You blithering idiot! You flabby rotter! You feeble crock!” He used to have me simultaneously terrified and bursting with laughter I was trying desperately to contain.’

With Greaves as a full member, the club again gained first place in the Wright Competition, winning every game except that against Liverpool Collegiate, which was drawn. A photograph of the victorious team, with a studious-looking Greaves seated on left front and Mr Moat standing in the centre of the back row, took pride of place in The Visor. For 1930–1, his final year, Greaves was elevated to the position of captain of the club. Alas, his team proved unsuccessful in its efforts to retain the Wright Shield, which was captured by their rivals, Liverpool Collegiate.

Debating

Physical-contact sports did not attract Greaves at the school, as is suggested by the absence of his name in the magazine’s sports reports. Rather, he displayed bravery in the battle of ideas with his involvement in the debating society, as was shown in the Easter 1929 edition of The Visor:

‘The third debate [of the term] was “That the time has come for India to be granted self-government”, which was proposed by Messrs Greaves and Pritchard on the grounds that only Indians are fit to govern Indians, and opposed by Messrs Drover and Bird, who stated that under the present racial conditions, India is unfit to rule herself. This motion also was lost.’

The motion was defeated, but Greaves’s failure to convince his peers should be seen in the context of the dominant attitude among the Birkenhead Institute boys, which was supportive of their country’s imperial and militaristic traditions. This was shown at an earlier debate entitled ‘That the best way to prevent war is to prepare for it’. The topic was prompted by moves towards general disarmament then being discussed at the League of Nations in Geneva and in opposition to rising anti-war sentiments in left-wing circles in Britain. Unsurprisingly, the motion was carried by a majority of the boys at the debate.

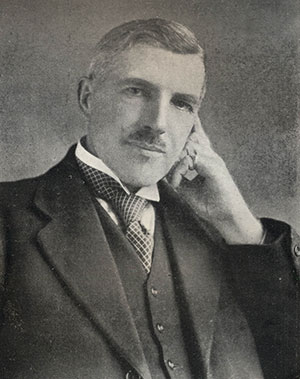

Liverpool Botanical Society

Greaves put his nascent presentational skills to further use before the school’s scientific society with a paper entitled ‘Early Evolution of Plant Life, showing the transition from Algae to Lichens and through Mosses to Ferns’. This initiative flowed from his involvement in the Liverpool Botanical Society, which he had joined as a junior member at the age of fifteen. He attended monthly meetings of the society and was much impressed by a leading member, the naturalist and working-class intellectual Dr William Arthur Lee of Wallasey, who was of Irish descent and a radical in his political views.

Greaves’s first piece of published prose, in the summer 1930 issue of The Visor, was inspired by Jonathan Swift’s Modest proposal (1729), a copy of which came to him from his grandfather on the Irish side of the family. In a satirical article of 340 words, ‘The new Arcadia’, and drawing on his knowledge of chemistry, he put forward a proposal for ‘a panacea for all human ills’:

‘My suggestion is that, by Act of Parliament, the Government should offer free destruction—absolutely gratis—to all people who are in any way dissatisfied with their present lot. A small dose of Prussic acid injected into the unhappy would ease them of their difficulties so totally and completely that they would never wish the Government to pass any law to recreate them.’

Greaves’s time at the Birkenhead Institute came to an end in the summer of 1931. His name appears in The Visor, under the heading of Valete (farewell), with a summary of his club and society involvements and his academic achievements. These recorded that in his final exams he had added the Higher School Certificate to his Matriculation Certificate (secured two years before), and, in addition to achieving a distinction in chemistry, he had studied a total of eleven subjects, five of which he passed with credit: English literature, history, French, mathematics and physics.

Tribute to Wilfred Owen

A significant postscript to Greaves’s involvement with the Birkenhead Institute came after he had moved on to the University of Liverpool. When his poem ‘Peredur’s Tree’ (based on the tale of the character Peredur in the Red Book of Hergest, a fourteenth-century collection of Welsh legends expressed in poetry and prose and known collectively as the Mabinogion) was published in the periodical Poetry Review, he was contacted by his old headmaster, E. Wynne Hughes. He asked Greaves for permission to carry ‘Peredur’s Tree’ in the Christmas 1933 edition of The Visor and commissioned him to write an appreciation of the First World War poet Wilfred Owen, who had been a pupil at the school from 1901 to 1907. Greaves contacted James Smallpage, the headmaster during Owen’s time there. He told Greaves that Owen had had a special chum at school, A.S. ‘Sandy’ Paton of Tranmere, who could provide Greaves with primary evidence to inform his article. Greaves, who interpreted Owen’s work from an anti-war standpoint, had to tread carefully in view of the school’s ethos of reverence for its 88 Old Boys who had fallen during the war. Entitled ‘Wilfred Owen: war poet’, in a mere 500 words his article in The Visor shows considerable background knowledge about Owen’s birthplace of Oswestry in Shropshire, paints a convincing portrait of the youthful Owen’s personality, and articulates an understanding of the evolution in Owen’s wartime poems that include some themes not related to the conflict—suggesting that Owen was a true romantic or mystic poet whose future was ‘wrenched away by the war from his proper métier’. Having provided an example of how Owen added a new system of dissonant rhyming to the art of poetry-writing that had since been taken up by other poets, Greaves finished with a generous salute:

‘When one reflects that his poetry was written in what snatches of leisure come the way of an officer in the front line, his achievement approaches the miraculous’.

In line with the content and spirit of Greaves’s article is sculptor Jim Whelan’s ‘Futility’, a bronze memorial that depicts a demoralised World War One soldier in a sitting position. It is located in Hamilton Square, Birkenhead, and was unveiled not on Armistice Day but rather on 4 November 2018 to mark the centenary of the death during a battle at Ars in northern France of the Birkenhead Institute’s most celebrated son.

By taking full advantage of the school’s academic and societal facilities, along with his mentors in the botanical society, Greaves was well equipped to bring his sharp mind and range of talents and skills to bear on the opportunities that lay ahead in his university, scientific and political life.

Michael Quinn is currently writing a biography of Desmond Greaves, with the support of his literary executor, Anthony Coughlan.

READ MORE

Dr William Arthur Lee (1870–1931)

FURTHER READING