The first balloon crossing of the Irish Sea in July 1817.

By Mark Davies

Among the many people awaiting his return was his father, James, who had dramatically failed in a similar quest five years earlier. James Sadler (1753–1828), a pastry cook and confectioner by trade, had become the unlikely first Englishman ever to fly when he ascended in a hot-air balloon in his home city of Oxford on 4 October 1784. This was less than a year after the first manned flight ever made, in France, and only a few weeks after the first flight by anyone in Britain, accomplished by the Italian Vincenzo Lunardi on 15 September 1784.

James Sadler’s unsuccessful attempt, 1812

Back in 1785 Sadler had been thwarted by bad luck in his ambition to become the first man to fly across the English Channel. In September 1810 he had succeeded in being the first to fly over (but then into!) the Bristol Channel. Two years later he set his sights on crossing another symbolically significant stretch of open water, the Irish Sea, and arrived in Dublin towards the end of August 1812 with that specific purpose in mind. To raise funds and interest, he displayed his extravagantly decorated balloon and car in the Rotunda, as had many other balloonists before him; the latter was diplomatically emblazoned with the words ‘Erin go Brah’.

The launch was made on 1 October from Belvedere House in Drumcondra (now part of St Patrick’s College). In attendance that day, joining thousands of others who had made special journeys into the city, was the novelist Maria Edgeworth (1768–1849). Her long description captured the attraction, anticipation and anxiety of a balloon ascent more vividly than any other of the period: ‘Crowds in motion even at nine o’clock in the streets: tide flowing all one way,’ she wrote, and ‘such strings of carriages, such crowds of people on the road and on the raised footpath, there was no straying: troops lined the road at each side: guard with officers at each entrance to prevent mischief.’ Then, a little before 1pm: ‘The drum beats! the flag flies! balloon full! … No one spoke while the balloon successfully rose, rapidly cleared the trees, and floated above our heads: loud shouts and huzzas, one man close to us exclaiming, as he clasped his hands, “Ah, musha, musha, GOD bless you! GOD be wid you!” ’

Well, if God was with the 59-year-old Sadler that day, it was not for the entire journey! Blown far northwards, and then back again, he resisted a landing on Anglesey in order to continue towards his preferred destination of Liverpool, ‘a City to which I was bound by every tie of friendship’, as he wrote in his own published account, Balloon: an authentic narrative of the Æerial Voyage of Mr Sadler. This decision proved his undoing. At 5.30pm, with the light failing, he pitched into the sea, but, finding no assistance, managed then to ascend for a second time, so that ‘the Sun whose parting beams I had already witnessed, again burst on my view, and encompassed me with the full blaze of day’.

After another 30 minutes, with his gas expended, Sadler again hit the water, and after an hour at the mercy of the wind and waves was rescued with some difficulty by a passing Manx herring boat, which took him and his equipment to their destined port. This, as it happened, was Liverpool, so Sadler did achieve his objective, though hardly in the way he had intended! His consolation would come five years later, when he assisted his youngest son Windham to succeed where he himself had so gamely failed.

Windham Sadler

Before this crowning achievement of his aeronautical career, however, Windham Sadler—who had made his first flight at the age of seventeen in 1813—made two other Irish ascents. The first was from Cork on 2 September 1816, the first ever seen in the city. The location was what is now Collins Barracks, at the top of St Patrick’s Hill, the Cork Advertiser writing that ‘the amiable and intrepid youth having … bade adieu to his venerable father … rose majestically grand and soared sublime on fields of ether towards the skies’. After a relatively straightforward ten-mile flight, Windham was accommodated overnight at Fountainstown by the resident farmer, George Hodder—the farm is to this day still run by the Hodder family—before returning to Cork the next day.

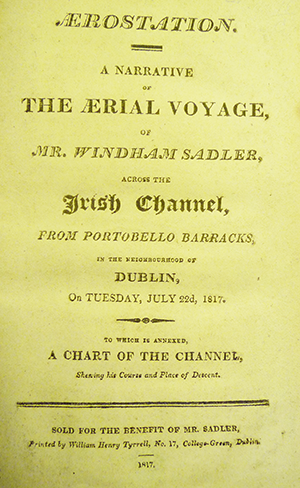

Windham’s other Irish ascent that year was from Dublin. It might well have been his last. On 5 November he and his companion, Belfast-born Edmund Livingston, landed not in England, as they had hoped, but in Ticknevin Bog (near Edenderry), in quite the opposite direction! With night falling, it was only the distant barking of a dog that enabled them to stumble their fortunate way to safety. Undeterred, Windham was back in Dublin the following year. For the only time in 30 ascents he published his own account, calling it Aerostation: a narrative of the aerial voyage, of Mr Windham Sadler, across the Irish Channel. It was, like his father’s account in 1812, printed in Dublin by W.H. Tyrrell.

The flight

The departure was at 1.20pm on 22 July 1817 from the Portobello Cavalry Barracks (today’s Cathal Brugha Barracks). Among the ‘vast concourse of people, of every class and description’, was his father, present at one of his son’s launches for the last verifiable time. By about 4pm, approaching Anglesey, he ‘exceedingly rejoiced’ at the sight of two vessels heading in the direction of Dublin, because ‘they would not only see my then state of security, but most probably my safe descent, and be the means of early communication of the facts, so as to remove all anxiety from the bosom of my father and friends’. Expertly, a ‘safe descent’ is what he contrived about two miles from Holyhead, and ‘at five minutes after seven o’clock I trod on the shores of Wales’. For a significant first in aviation history it had apparently all been remarkably straightforward and uneventful. (Since then, the journey has apparently been made fewer than half a dozen times.) Windham rested at the Holyhead home of John Macgregor Skinner, a well-known Holyhead–Dublin packet-boat captain, who seems likely to have been instrumental in authorising his contrasting underwater journey in the diving bell.

Edmund Livingston went on to make several more flights, including the first ascent ever seen in his home city of Belfast in 1824. In 1822 he also joined the list of those men whose attempts to cross the Irish Sea ended with having to be rescued from it! Windham made one further flight from Dublin on 14 July 1824, departing with Livingston from the Coburg Gardens. It was one of the last that he ever made. On 29 September that year Windham Sadler became only the second ever British ballooning fatality, dying in a gruesome accident after ascending from Bolton.

Windham’s father James, by then residing in the Charterhouse Hospice in London, lived out his remaining years in impoverished anonymity, and was buried back where he was born, in Oxford, in March 1828. His passing was barely noticed at the time, and to this day Oxford has accorded the former pastry cook only token public acknowledgement. Dublin has done very much better in commemorating the memory and achievements of its own local aeronautic pioneer, Richard Crosbie.

Mark Davies is an Oxford local historian, guide and public speaker.

Read More:

Richard Crosbie

FURTHER READING

M. Davies, ‘King of all Balloons’: the adventurous life of James Sadler, the first English aeronaut (Stroud, 2015).