Philomena Connolly

On 11 July 1332, Sir William Bermingham was taken from Dublin Castle where he had been imprisoned, and was hanged by order of Anthony Lucy, the justiciar. The Dublin annalist was horrified at this deed: ‘Alas, alas,’ he lamented, ‘who can contain their tears when they remember his death?’ The shock of the execution was partly because of William’s personal qualities—he was universally described as a noble, daring and fearless knight—but also because of his position. He was lord of Carbury in County Kildare and married to the widow of Richard de Clare, lord of Thomond. His brother John, Earl of Louth, had been justiciar in 1321-3 and William had served as John’s deputy for six months during that period. However, in the years since then, William had become closely associated with Maurice fitzThomas, who was created Earl of Desmond in 1329, and it was this association that was to lead to his downfall.

Good relations with Mortimer

Maurice fitzThomas was quarrelsome, hot-headed and cared little for authority. In 1327-8 a dispute with Arnald le Poer, probably originally over land, had escalated into open war, with fitzThomas receiving assistance from the Berminghams and Butlers against le Poer and his allies the de Burghs. Some form of settlement was reached in 1329 with the intervention of the justiciar, and fitzThomas was given the title of Earl of Desmond. William Bermingham established good relations with Roger Mortimer, regent for Edward III, and was restored to official favour, taking part in the justiciar’s campaign against Brian Bán O’Brien in County Limerick in the spring of 1330. Desmond took part in the same campaign, but by the end of April was encouraging disobedience to the king’s officials and in May harboured Brian Bán after he had killed the sheriff of Limerick. He was arrested and charged with aiding and abetting O’Brien but managed to escape from prison in Limerick.

The downfall of Mortimer in 1330 and the assumption of personal rule by Edward III meant that the new English government was determined to assert its authority and early in 1331 turned its attention to Ireland. Measures were taken for the reform of the Irish administration and all grants made since Edward III’s accession in January 1327 were revoked, which effectively meant all those made while Mortimer was in power. Sir Anthony Lucy, a knight with experience on the Scottish border who had no previous connection with Ireland, was appointed justiciar to implement this policy, and it was his appointment that was the catalyst for the bizarre events which ensued.

Challenge to the justiciar’s authority

The news of Mortimer’s fall obviously alarmed both Desmond and William Bermingham, who had benefited from grants in the period 1327-30. Desmond’s title of earl was threatened by the act of resumption as was Bermingham’s possession of lands in Meath and Tipperary. Both failed to attend the parliament held at Dublin in January 1331 and when another parliament was summoned by Lucy in the summer, Desmond and other magnates, possibly including Bermingham, were absent, so presenting a direct challenge to the justiciar’s authority. Lucy managed to get Desmond and Bermingham to submit in August, granting them pardons for their previous misdeeds, but this was not the end of the matter. What happened in the meantime is not clear, but on 16 August Desmond was arrested at Limerick, held there until October and then transferred to Dublin Castle. A series of inquisitions were held in Limerick and Tipperary which produced a stream of accusations against Desmond. He was indicted of a wide range of offences, including aiding and abetting Brian Bán, arranging an attack on Bunratty castle in 1325 and desiring ‘to obtain the whole land of Ireland for himself and crown himself as a false king’.

William and Walter Bermingham arrested

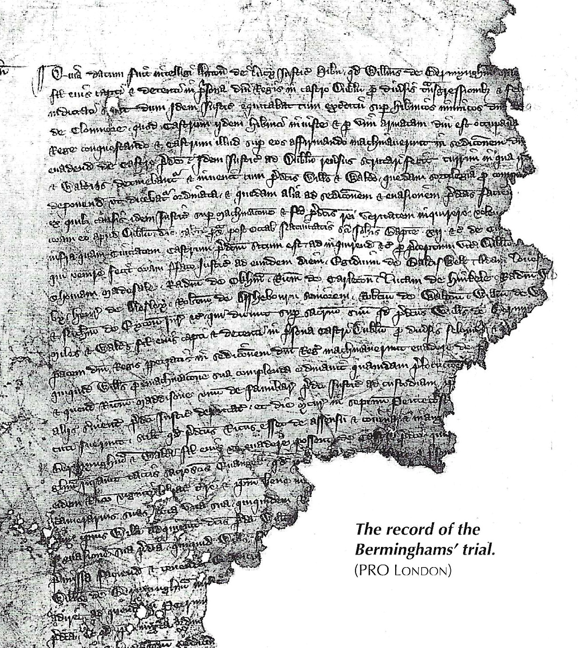

At this stage there was no mention of Bermingham being involved, but further indictments were to follow. On 17 February 1332 a jury at Clonmel exposed a conspiracy in 1327 which had as its supposed aim the installation of Maurice fitzThomas as king of Ireland. Maurice’s alleged co-conspirators included William Bermingham, Brian Bán O’Brien and Richard Ledred, bishop of Ossory. Lucy acted immediately, arresting William Bermingham at Clonmel, according to one account while he was on his sick-bed, and holding him locally until he had concluded his business in Munster. William’s son Walter, whose involvement in the conspiracy was obviously of a lesser nature, was also indicted and arrested. In March, another jury at Limerick uncovered a further conspiracy in 1331, again with Desmond as its focus. It was alleged that Desmond, William Bermingham, Walter de Burgh, Brian Bán O’Brien and Mac Namara had conspired to make Desmond king of Ireland and then divide the country, with Desmond taking Munster and Meath, Bermingham taking Leinster, Walter de Burgh Connacht and the absent Henry de Mandeville Ulster.

Robin Frame has shown the unlikely nature of these conspiracies, involving people who were more likely to be opposed to each other than plotting together, but it is possible that the authorities were prepared to believe Desmond capable of anything. At any rate, nothing could be lost by keeping the supposed conspirators in custody. On 19 April 1332 William and Walter Bermingham were moved to Dublin Castle where Desmond and Henry de Mandeville had been imprisoned since the previous year. Walter de Burgh was in the custody of his cousin, the Earl of Ulster, in Northburgh Castle. It is not clear what the government intended to do next. Desmond and the Berminghams had been indicted for felony, on various counts, and the next step should have been their trial on the charges produced by the juries in Limerick and Tipperary. Perhaps because of the importance of the people involved, the authorities hesitated and the prisoners were left cooling their heels in Dublin Castle while Lucy went south to recapture the castle of Clonmore in County Carlow from the native Irish.

Escape plot discovered

Lucy was attending to the re-fortification of Clonmore after its capture when news reached him of the discovery of an escape plot in Dublin. William Bermingham had made an agreement with Richard Madison, one of the justiciar’s household who had been charged with his custody. William was to employ Richard as his chamberlain for life and give him land worth £20 a year; in return Richard was to go to the house of a certain Peter and procure a rope by which William and Walter could reach the ground and so escape. William also arranged for forty armed horsemen and two hundred foot soldiers to come to Dublin on the night of 2 July 1332. These were to come right up to the walls of the city and castle, meet William and Walter when they had escaped, and escort them away from Dublin, presumably to William’s lands in County Kildare. We do not know how the plot was discovered, but the fact that Richard Madison later received a reward for good service from the Irish exchequer implies that William’s trust in him was misplaced. When Lucy heard the news, he rushed back to Dublin and conducted a search of the tower where the Berminghams were being held. This resulted in the discovery of what were described as ‘certain magical objects intended, as it was said, for removing fetters’ and also ropes and other unspecified things for use in the escape. The watch in the city and castle was intensified, and when, on the night of 2 July, the 240 men came to Dublin as arranged, they realised that the plot had been discovered and retreated, burning houses in the suburbs as they went.

The mechanics of the escape

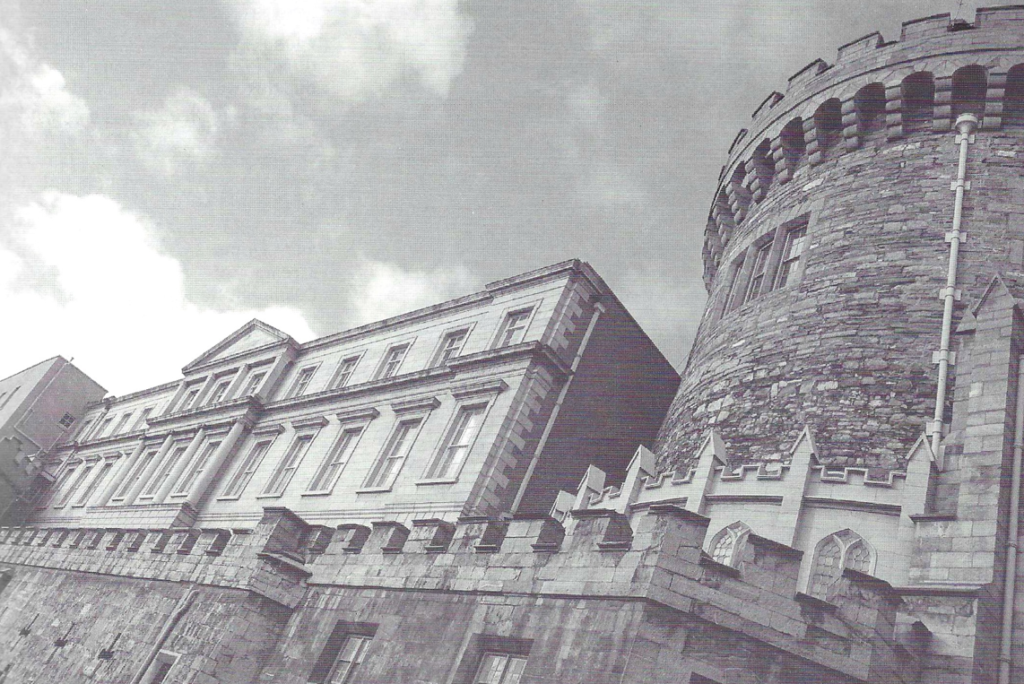

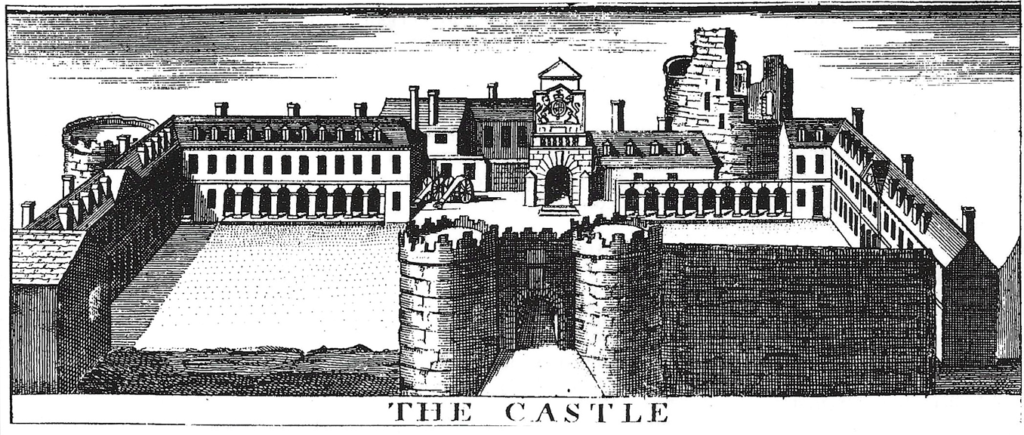

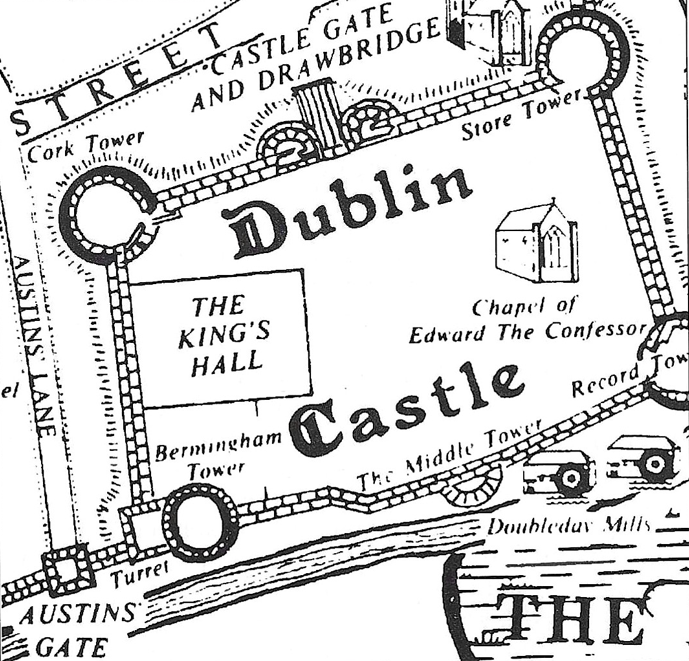

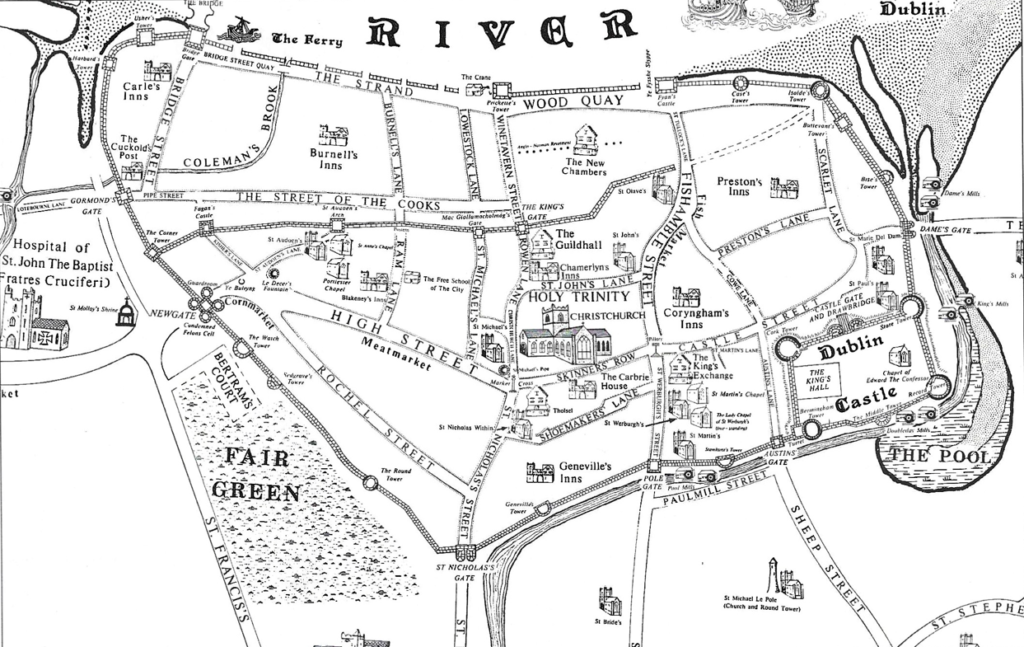

The official account of the plot is vague on the mechanics of the escape, but the available information enables us to make some deductions. First of all, we know that the Berminghams were held in a tower in the castle. The medieval castle was essentially a rectangular structure open in the middle, with towers at each corner as well as two gate towers on the north side, but there is no detailed evidence on the purposes for which the various towers were used in the medieval period. The castle jail, which housed ordinary prisoners, was a building adjoining the north-west tower, but important prisoners were kept in the towers themselves and it is clear from the nature of the Berminghams’ offence, as well as from the mention of fetters, that they were regarded as high-risk prisoners. They were kept apart from their fellow conspirators, Desmond and Mandeville, as there is no mention of either of these being involved in the escape attempt. There was a tradition in the seventeenth century that the south-west tower had been used for housing prisoners in the past. It is called Bermingham’s tower in a grant of land dated 1412 but the origin of the name is unclear. Stanyhurst, writing in the sixteenth century, suggested that it might have been built by a Bermingham, or that the name had resulted from the imprisonment of a Bermingham there. John Bermingham, William’s brother, has sometimes been credited with erecting it during his period of office in the early 1320s, but it is unlikely to have been built as late as this, so the suggestion that the tower got its name from the imprisonment of the Berminghams there cannot be discounted.

Then there is the statement that William’s supporters were to come up to the walls of the city on both sides, to protect the Berminghams after their escape. This phrase could literally mean inside and outside the walls, but the account makes it clear that they came within sight of the city and realised that the watch had been increased. Therefore, it must refer to two adjoining sides of the city walls from the outside, and this narrows the possibilities. The north side of the city is ruled out for obvious reasons—the river, the distance from the castle and the fact that it was unlikely that the Berminghams would be heading north. On the south side, the combination of east and south walls is ruled out by the mention of walls of the city rather than walls of the castle which would be more appropriate. So we are left with the combination of the south and west walls, which appears much more probable. The men could deal with any pursuit and could also defend the bridges after the Berminghams had crossed. Furthermore, we are specifically told that when the escape failed, they retreated through the suburbs, in this case, the southern suburbs of the city.

All this supports the theory of an escape from the Bermingham tower, probably directly down from the tower to the ground beside the river Poddle. The Bermingham tower was demolished and rebuilt in 1775, but a description of the exterior of the walls and towers of the castle in 1585 shows that on the first floor, the window faced west along the city wall; on the second, the window faced east along the castle wall; while on the third and top floor, there were two windows, one facing west, the other south-east. The top storey seems most likely, given that the rope obtained from Peter was between 66 and 114 feet long (unfortunately, the document giving an account of the plot is damaged at the crucial point in the text), and the Bermingham tower may have been about 90 feet high. Once on the ground, the Berminghams could go westwards along by the wall to the bridge at the Polegate, and from there across to the southern suburb, with their supporters protecting them from behind. The fact that their men were to come up to the city wall implies an escape across one of the bridges rather than by fording the river opposite the castle. The same route may have been used in an escape attempt in 1313, when Finola, the wife of Walter Mac Torkill, came to Dublin with sheets and coverlets for her husband and his companions to make ropes in order to descend the castle walls, but although we hear of a number of escapes in the medieval period, no details are recorded.

Iron fetters a problem

Before descending any rope, the prisoners would have to get free of the fetters around their ankles. The fetters used at this period were made of two semi-circles of iron, held together by two iron pins. A prisoner might have fetters on both ankles, joined by an iron chain, or a fetter might be attached by a chain to a ring in the wall. The normal way of removing them was by hammering the pins out of their holes. What then are we to make of the items found in the tower? One account refers to ‘certain magical objects intended, as it was said, for removing fetters’ while the other calls them ‘devices made by magic’, but unfortunately neither elaborates on these descriptions. First of all, it would appear that we are dealing with physical objects. It is unlikely that the Berminghams would have relied on amulets or magic words for removing fetters, especially as the remainder of their plan, including the provision of the rope, was very practical. One possibility is that ordinary objects, such as hammers and pincers, were involved. Perhaps it was not known how they were introduced into the tower, and so the suspicion arose that they had been made by magic. The difficulty with this explanation is that hammers and pincers were familiar objects, whereas the use of the phrase ‘as it is said’ implies that the practical purpose of these ‘devices’ was not immediately apparent. The other possibility is that the objects were totally unfamiliar in this context, but without more information it is impossible to speculate as to their nature. Whatever they were, there was no opportunity to use them once the plot was discovered.

Legal technicalities

After the tower had been searched and the objects discovered, a jury was summoned on 4 July to inquire into the matter and on 10 July, William and Walter were charged before the justiciar with attempted escape. This is where legal technicalities came to the fore. William pleaded not guilty, but his son Walter, although a layman, claimed benefit of clergy and the jury agreed that he was literate and therefore entitled. This meant that he could not be tried in a secular court, but should be returned to prison until a representative of some bishop claimed him; he could then be dealt with in an ecclesiastical court, and if guilty, did not run the risk of the severe penalties imposed in the secular courts. The practice at the time was to establish the person’s guilt before handing him over to the ecclesiastical authorities so the jury had to deal with the charges against both father and son. Both were declared guilty. William was sentenced to death, to be dragged behind horses to the place of execution and there hanged, and his lands forfeited to the crown. If someone was imprisoned on an indictment and was found guilty of trying to escape, he automatically incurred the sentence appropriate to the original offence, although he had never been tried for it, presumably on the grounds that flight was an admission of guilt. William had been indicted of felony and the sentence was death and forfeiture. The execution took place on the following day, but the first part of the sentence was remitted by the justiciar either on compassionate grounds or to avoid a possible cause of public disturbance. Walter was more fortunate. He was returned to Dublin Castle to wait for a bishop to claim him, which never happened, and remained a prisoner until 1334. After his release he underwent a complete rehabilitation, securing restoration of his father’s lands, marrying an English heiress and even serving as justiciar himself in the 1340s.

(Courtesy of The Friends of Medieval Dublin)

Trumped-up charge?

It has been suggested that the story of the escape attempt was a trumped-up charge to enable Lucy to get rid of the Berminghams, but the balance of probability is in favour of a real attempt. The administration had nothing to gain from inventing the charge, especially as the Berminghams were not the leaders or the focus of either conspiracy. Once the plot was discovered, rapid action was necessary to prevent anyone else from following their example. The news of the escape plot came as a shock to Lucy and his colleagues. It proved that Dublin Castle was not secure, even with Lucy’s men forming the garrison. Communication with the outside was possible, to the extent of arranging for a private army to come up to the city walls to assist in an escape. If the Berminghams could do this, what was to stop Lucy’s most important prisoner, Desmond, from doing likewise? The authorities may have been genuinely frightened by the mention of the ‘magical devices’, especially as only eight years had passed since the trial of Alice Kyteler for sorcery in Kilkenny (see HI Winter 1994). Not only had the normal physical security of the castle broken down, but prisoners were apparently prepared to use supernatural means in their escape attempts.

No-one was ever tried for involvement in either of the supposed conspiracies. Walter de Burgh died while a prisoner in Northburgh castle, supposedly of natural causes. Desmond and Mandeville were ultimately released from Dublin Castle on condition of giving security for their future good behaviour, and presumably the same course would have been adopted with the Berminghams, had they not tried to escape. The authorities may have doubted the truth of the allegations of conspiracy, or were unwilling to proceed against those who had been indicted for fear of the consequences. William Bermingham obviously felt that a trial was a distinct possibility and was not prepared to take the risk of conviction and execution. However, in attempting to escape, he took a far greater risk, which did not pay off. He would have been better advised to sit it out in Dublin Castle, or alternatively, to ensure that he was literate and so able to claim benefit of clergy.

Philomena Connolly is an archivist in the National Archives, Dublin.

Further reading:

R. Frame, English Lordship in Ireland 1318-1361 (Oxford 1982).

P. Connolly, ‘Select documents XLIV: An attempted escape from Dublin castle: the trial of William and Walter de Bermingham 1332’ in Irish Historical Studies xxix, no.113 (May 1994).

J.G. Bellamy, Crime and Public Order in England in the Later Middle Ages (London 1973).

G.O. Sayles, ‘The rebellious First Earl of Desmond’ in J.A. Watt, J.B. Morrall & F.X. Martin (eds.), Medieval Studies presented to Aubrey Gwynn SJ (Dublin 1961).