In 1913 Lord Northcliffe, proprietor of the Daily Mail, offered a prize of £10,000 for the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic by a ‘heavier than air’ machine. A seventy-two hour time limit was set under rules drawn up and administered by the Royal Aero Club. The competition was suspended for the duration of the first world war, but was renewed in 1918.

Fierce competition

Since the war’s ‘end, daring young men, usually wartime pilots, backed by aircraft manufacturers and entrepreneurs, were repeatedly setting new records for distance and speed.

Prizes were won as countries were crossed and cities linked by what was now accepted as the transport of the future. Regular commercial flights were already underway in Germany and France. Competition among manufacturers for air force and airline company contracts was fierce, and pilots and machines were tested to their limit.

By May 1919 several aircraft had gathered in St John’s, Newfoundland in preparation for the Atlantic challenge. On Sunday 18 May, at S.48pm GMT, Harry Hawker, the man thought most likely to succeed, with navigator Commander K. Mackenzie Grieve, took off in a Sopwith Rolls-Royce biplane and headed for the Irish coast. Hawker was a well-known Australian airman and Grieve was an American. All ships were advised of their departure and told that the plane would display a red light as a signal that all was well and as a request for position. Half way across the Atlantic, at 1.1Oam Monday, the steamer Samnanger saw the red light of the Sopwith and signalled its position. The steamer received a weak wireless signal in response, but this was unintelligible, and the operator could not say for sure whether it was from the aeroplane or another steamer.

Last contenders

Also on the ocean that night was the steamer Glen Devon, out of London for St John’s. It also picked up the transmission and, thinking the Sopwith was well on course for Ireland, thought no more of the encounter. On board were Capt. John Alcock and navigator Lieut. Arthur Whitton Brown, the last contenders for the Daily Mail prize. Their Vickers Vimy biplane was stored in the cargo section along with twenty-three drums of petrol on the poop deck ‘at shippers risk’. The airmen may well have felt down-hearted when they learned that Hawker and Grieve had passed over them during the night. In fact the garbled message received by the Samnanger was probably a distress signal: the Sopwith’s water pipe between the radiator and pump had blocked and it was forced to ditch close to the Mary, a Dutch steamer on route from New Orleans to Horsens in Denmark. It was six days before word of their rescue reached Britain.

Who would be first away?

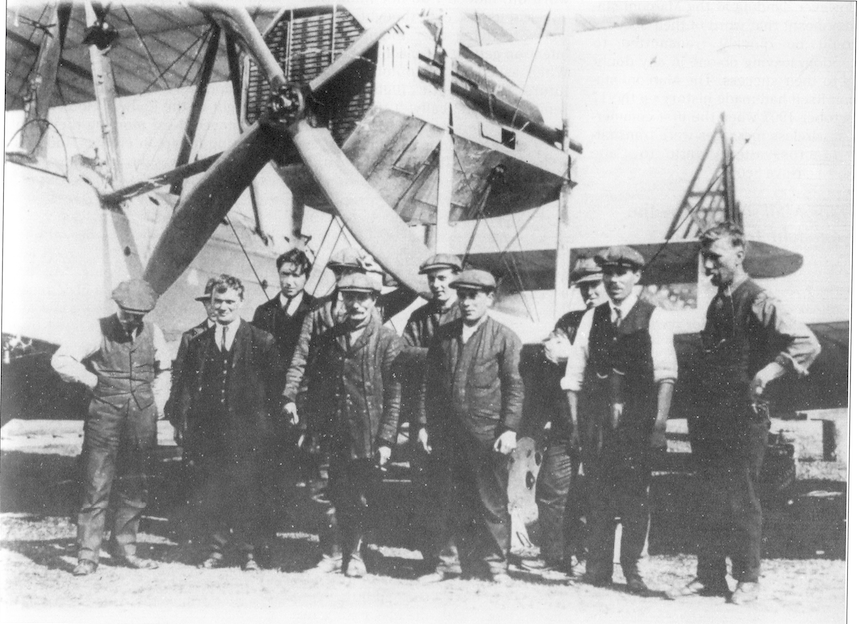

Meanwhile Alcock and Brown arrived at St John’s on Sunday 25 May, the very day that news of Hawker and Grieve’s rescue was telegraphed around the world. All the best sites had already been taken so the Vickers team were left with Lester’s field, considered by the rest to be unsuitable. Hawker and Grieve’s near achievement and brilliant rescue heightened competition among the teams and the urgency to get in the air grew with each passing day. A series of test flights were carried out on the Vickers Vimy. At the same time a Handley Page machine, piloted by Admiral Mark Kerr, was also being tested and speculation grew as to who would be first away. On Thursday 12 June Mr Muller, the manager of the Vickers Company, arrived on the steamer Graciana with a new supply of petrol. Alcock and Brown were delighted with the consequent enhanced performance in further tests and announced their intention ‘to get away on the transatlantic flight’ the next day.

Damaged axle

However the next morning it was discovered that they had damaged an axle on landing the night before which required repairs, so the flight was postponed until Saturday 14 June. Saturday morning brought strong winds and it seems almost certain that Alcock would again have postponed the flight had he not received word that Admiral Kerr intended to set out later that day. So the decision to go was made. As the airmen prepared for the gruelling hours ahead, an accident occured which almost prevented their take off. There was a strong wind blowing across the field and the plane was tied down with ropes and pickets. One rope loosened, got caught in the under carriage, and wound around the copper petrol pipes, severely indenting them. Mechanics set to work replacing the pipes. Meanwhile, ‘stretched on the ground in the shadow of the Vimy’s wings’, the airmen took their last meal in Newfoundland: tongue, bread, potted meats and coffee. Both men were in high spirits and Brown told reporters: ‘With this wind, if it continues all the time, we shall he in Ireland in twelve hours .. .I am steering a straight line for Galway Bay and although I shall do my best, I do not expect to strike it off exactly.’ ‘This wind amuses me,’ Capt. Alcock commented, ‘A few years ago it would have “put the wind up” badly. In the very early days, long before the war taught us what flying really is, weused to scatter pieces of paper and if they blew away we would not dream of taking a bus out’. All repairs were completed and the aeroplane took off at 4.13pm GMT, Saturday 14 June 1919. It climbed slowly at first, then picked up the westerly winds over the coastline and headed out over the Atlantic.

Alcock

Both Alcock and Brown were experienced flyers and aeroplanes had been the main passion of their lives from an early age. Capt. John Alcock was born in Manchester twenty-six years earlier and served his engineering apprenticeship with the British Westinghouse Company, and afterwards with the Empire Company. He was the first man to fly across country at night. In 1913 he took part in the London to Manchester flight. At the outbreak of war he. became attached to the · designer department of the Royal Naval Air Service. He was sent to the Greek island of Lemnos and there set records for long-distance bombing flights. While on a raid over Constantinople he was forced down by engine trouble and ditched his plane in the Gulf of Saros. After swimming for many hours he and his companion reached land only to be taken prisoner by the Turks. He was released on the signing of the Armistice, and awarded the DSC for his service. Alcock then joined the Vickers company and concentrated on the problems of Atlantic flying.

Brown

Lieut. Arthur Whitton Brown was thirty two. Born of American parents, his family moved to Manchester when he was young. After completing his studies at the Manchester College of Technology, he joined the British Westinghouse Company and worked in South Africa, Germany and France. At the outbreak of war he tried to join the Flying Service, but was turned down, so instead he became a second lieutenant in the Manchester Regiment. In 1915 he succeeded in obtaining a transfer to the Royal Flying Corps. He was twice shot down over enemy lines. On the first occasion he crashed his plane to prevent it being captured by the Germans. It caught fire, and although badly burnt, he still managed to make his way to British lines. On the second occasion he was not so fortunate, his leg was badly injured in the crash and he was taken prisoner. However, the Germans later handed him over to the Red Cross, ‘as one not likely to recover’. Back in England Brown quickly recovered and, although left permanently lame from the crash, he volunteered for service and became an instructor at Peterborough.

The flight

The Vickers Vimy was produced too late to participate in the war but was then under consideration by the Royal Air Force, and was eventually commissioned by them in July 1919. The plane was of all steel manufacture and was forty-two feet eight inches long and had a wing span of sixtyseven feet. It was fitted with two 360hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines and was capable, fully loaded, of ninety miles per hour, and with the throttle wide open, of one hundred and fifteen miles per hour. On the flight across the Atlantic, with the following winds, Alcock and Brown averaged one hundred and twenty miles per hour. ‘I believe that the great secret of long distance flying’, Capt. Alcock told a reporter after the flight, ‘is to nurse your engine. I never opened the throttle once.’ For the first hour the weather was clear, but soon they hit thick banks of cloud and heavy fog. They had the wind in their tail for the entire flight and the crossing was rough and bumpy. Showers of sleet caused their radiator shutters to freeze up and the petrol gauges soon covered over with ice. They climbed to eleven thousand feet, but still could not break from the clouds. Visibility was so poor that they only caught sight of the water about six times throughout the journey. At one stage they ‘spiralled down to within ten feet of the water and flew as if upside down, without any sense of horizon.’ To add to their difficulties about half an hour out they started to lose their transmitter and so were unable to make contact with, or receive directions from , the ships passing beneath them. ‘Our only guide was the stars, and we got occasional sights of the moon.’ During the flight the men ate sandwiches and chocolate, and drank ale and coffee. Communication between them was down to a minimum, due to the roar of the engines and the darkness.

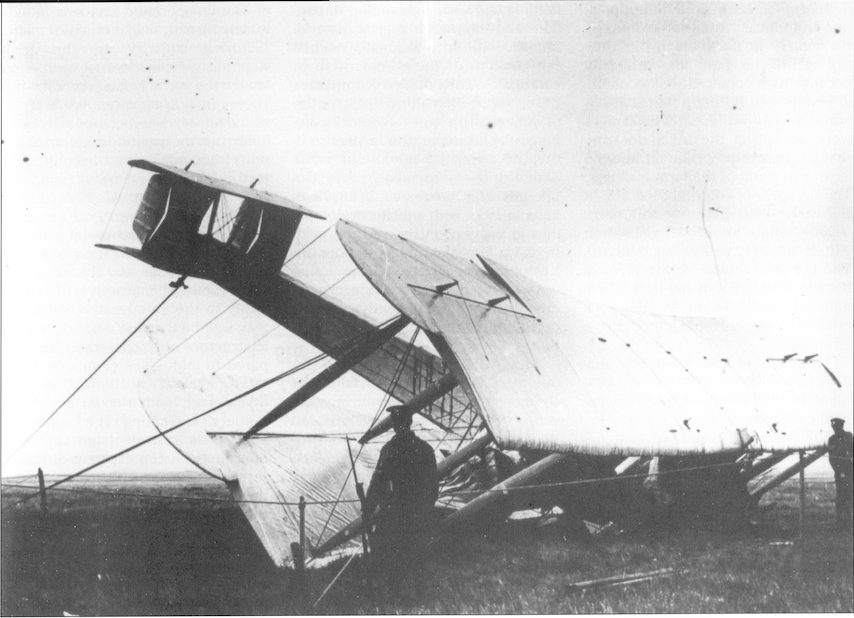

Nose-dive in a bog

Just two hours from landing, through a break in the clouds at 11,000 feet, they caught their first sight of the sun. This was a tremendous help in trying to determine their position. They first spotted Eeshal island and then Turbot off the Galway coast. ‘We were jolly pleased, I tell you, to see the coast’, Alcock told reporters. They circled the small town of Clifden before spotting the tall masts of the Marconi wireless station at Derrygimla, south of the town. Their arrival was witnessed by some to the town’s inhabitants, but it being a Sunday, the majority were attending church services and only heard the roar of the engines. The aeroplane headed towards the station and landed behind the condenser house, on what looked from the air like level ground, but which in fact turned out to be bog. At first the plane ran for about fifty yards, then the wheels began to sink, and ‘a nose-dive brought her to a dead stop’. Whitton Brown later told reporters: ‘One of the special features of’ the VickersVimy machine was its steel construction, and I believe that it was owing to this type of construction that the landing at Clifden was not more serious. Had it been of the wooden type of construction I believe that the machine would have crashed on Capt. Alcock and myself’. As it was there was little damage done and the airmen stepped out, safe and unhurt, and onto Irish soil. It was 8.40am GMT, Sunday 15 June 1919. It had taken them sixteen hours and twentyseven minutes to fly the 1,900 miles from St John’s. The operators on duty at the station went out to greet them. ‘I’m Alcock-just come from Newfoundland,’ the Captain announced, while Lieut. Brown remarked: ‘That is the way to fly the Atlantic.’

On discovering the identity and achievement of the flyers, one operator requested their autograph, the first of many they would sign. ‘Now’, Capt. Alcock said, ‘if we had a shave and bath, we should be all right.’ Two-thirds of the aeroplanes fuel had been used up, and had it not been for the poor landing conditions, the flyers had intended taking off again and continuing their journey to London.However, landing at the Marconi station meant that word of their success could be quickly transmitted to London, leaving no-one in any doubt as to their success. The Marconi station itself had made history on the 17 October 1907 when the first commercial wireless messages were transmitted across the Atlantic to Cape Breton, Nova Scotia.

Daily Mail scooped by the Connacht Tribune

The story of the Alcock and Brown flight was to have been a Daily Mail exclusive; a special correspondent had been in Galway for weeks awaiting their arrival. However the editor of the Connacht Tribune, T.J.W. Kenny, got to Derrygimla first and ‘scooped’ the story. He was the first to interview Alcock and sold the story internationally. Kenny was later congratulated by the Press Association (London) and the United Press of America on his ‘scoop’. He found Capt. Alcock relaxing at the station’s social clubhouse ‘looking as spruce, attired in a navy lounge suit, and cheerfully smoking a cigarette, as any city man enjoying an hour’s content’. When asked how he felt flying over such a vast ocean and in the dark, hereplied: ‘We have done a considerable amount of night flying in the past, the sense of loneliness that might be supposed to accompany it has long since worn off. Indeed I do not think that either of us had ever thought of what we were flying over, being merely intent on getting the machine across’. When asked for an opinion on the future for Atlantic flight, Alcock replied optimistically: ‘I think within the next twelve months … they will have a cross-Atlantic service’. Large crowds flocked to the station during the day, but were refused admission. However some people did wade ankle deep through the bog to see the plane, which was carefully guarded by the military. Despite this souvenir pieces of the wings were on sale in the town that evening. Monsignor McAlpine and J. King, chairman of the District Council, were among the first outsiders to meet the airmen. Both men, recognising an opportunity for promoting their town, after bidding the airmen ‘cead mile failte to Ireland’, added the hope ‘that their visit was but a prelude to the opening of a regular service across the Atlantic to the nearest point on the European side’.

First trans-Atlantic airmail

That evening the men were taken to Galway by the Marconi motor car. They carried with them ‘a little white mail bag with lead seals unbroken … [ containing) … eight hundred letters, including correspondence for the king and many nobilities’. This is the first Atlantic aerial mail’, Alcock explained. Ground crew from Oranmore arrived at Derrygimla to dismantle the plane and prepare it for shipping to London. At Galway Alcock and Brown were given a hero’s welcome and were entertained late into the night at the Railway Hotel where they stayed. Next morning they went shopping for fresh clothes and souvenirs. A Galway jeweller presented each of them with a Claddagh ring. ‘I shall always keep it and always wear it as a lucky charm’, Capt. Alcock told him. People stood in the rain for hours outside the hotel to witness their coming and going. At one o’clock they were given a civic reception and addresses of welcome and congratulations were presented from the Galway Urban and District Councils. Alcock thanked the people for their kindness. Both men were reluctant to accept all the praise lavished on them. Brown’s comment’ After all, even though the voyage has been a long one it was straight forward flying all the way’-was typical of the airmen’s modesty.

Trinity rag week

The men had to fight their way through a dense crowd gathered on the platform of the railway station to bid them farewell. They were cheered at every station and at Athlone Alcock was presented with a model plane. At Broadstone station in Dublin the crowds began to gather one hour before the train was due to arrive. It was Trinity ‘rag’ week and the students were in form for mischief. They took up front line positions on the platform and when the train pulled in, they lifted the airmen out of their carriage. They carried them shoulderhigh through the cheering crowd and placed them in two waiting cars. A cordon was formed around the cars which were then lead slowly through the streets and on to the front gates of Trinity College. While Capt. Alcock was lifted shoulder-high and carried to the doors of the Dining Hall, Lieut. Brown managed to escape to the Royal Automobile Club in Dawson Street. At the entrance to the Dining Hall a struggle broke out between ‘the parties inside, who were trying to keep the demonstrators out and the students who were trying to carry Capt. Alcock in’. Eventually an invitation was issued to Capt. Alcock to join the Provost at the Fellows’ table.Escorted by the Junior Dean, ‘Captain Alcock marched up the centre of the hall to take his seat at the right hand of the Provost. The whole hall rose to their feet and cheered vociferously’. Later he joined Brown at the Automobile Club and the airmen signed autographs for the students. That evening the two dined at the St Stephen’s Green Club, and were guests for the night of the Chief Secretary at his lodge in Phoenix Park.

On Tuesday morning the airmen left Kingstown harbour on board HMS Ulster. In a final interview Alcock thanked the people of Ireland for the wonderful reception they had received. ‘It was really a bigger strain on us than the flight’, he remarked. Letters and telegrams of congratulations arrived from all over the world. The one that caused the most controversy was from Lord Northcliff who concluded by saying: ‘I rejoice at the good augury that you departed from and arrived at those two portions of the British commonwealth-the happy and prosperous Dominion of Newfoundland and the future equally happy and prosperous Dominion of Ireland’.

Knighted

Later in the month at a lunch in the Savoy Hotel in London the airmen were presented with their prize money by Winston Churchill, on behalf of Lord Northcliff. The following day at Windsor Castle they were knighted by King George V. In December of the same year Sir John Alcock was killed on a flight from England to France, at Cote d’Evrard, north of Rouen. He was buried in Manchester. Sir Arthur Whitton Brown, always a shy, reserved man, was greatly affected by the death of his friend and never flew again. He died in 1948. Lester’s field is today part of the city of St John’s and the site is marked by two plaques commemorating the flyers . A monument to mark the landing site stands at Errislannon on a height overlooking Derrygimla bog near Clifden.

Kathleen Villiers-Tuthill is a local historian.

Further reading:

K. Villiers-Tuthill, Beyond the Twelve Bens: a history of Clifden and district 1860-1923 (Galway 1986).