By Joseph E.A. Connell Jr

Marriage was often afforded high status as a societal stabiliser in newly established states, and the Irish Free State, operative from 1922, was no exception. Unlike Northern Ireland, which adopted the parliamentary system of divorce, the Irish Free State provided no mechanism for private bills of divorce to proceed. Although a range of opinions existed on divorce provision, the government sought advice from the Irish Catholic hierarchy, whose position was steadfast: there should be no mechanism for divorce in the new state.

Whenever divorce law arose at Westminster, Ireland was always excluded. There was an understanding that divorce wasn’t popular among the Irish—Catholic or Protestant—and an interesting belief, endorsed by the Irish themselves, that Ireland was matrimonially ‘purer’. The truth was that, what with famines, land wars, evictions and the long shadow of the penal laws, most Irish people probably had other concerns than whether some swell could dissolve his marriage. Daniel O’Connell was against divorce. William Gladstone was against divorce, and praised Ireland’s lack of it. Edward Carson was also against divorce.

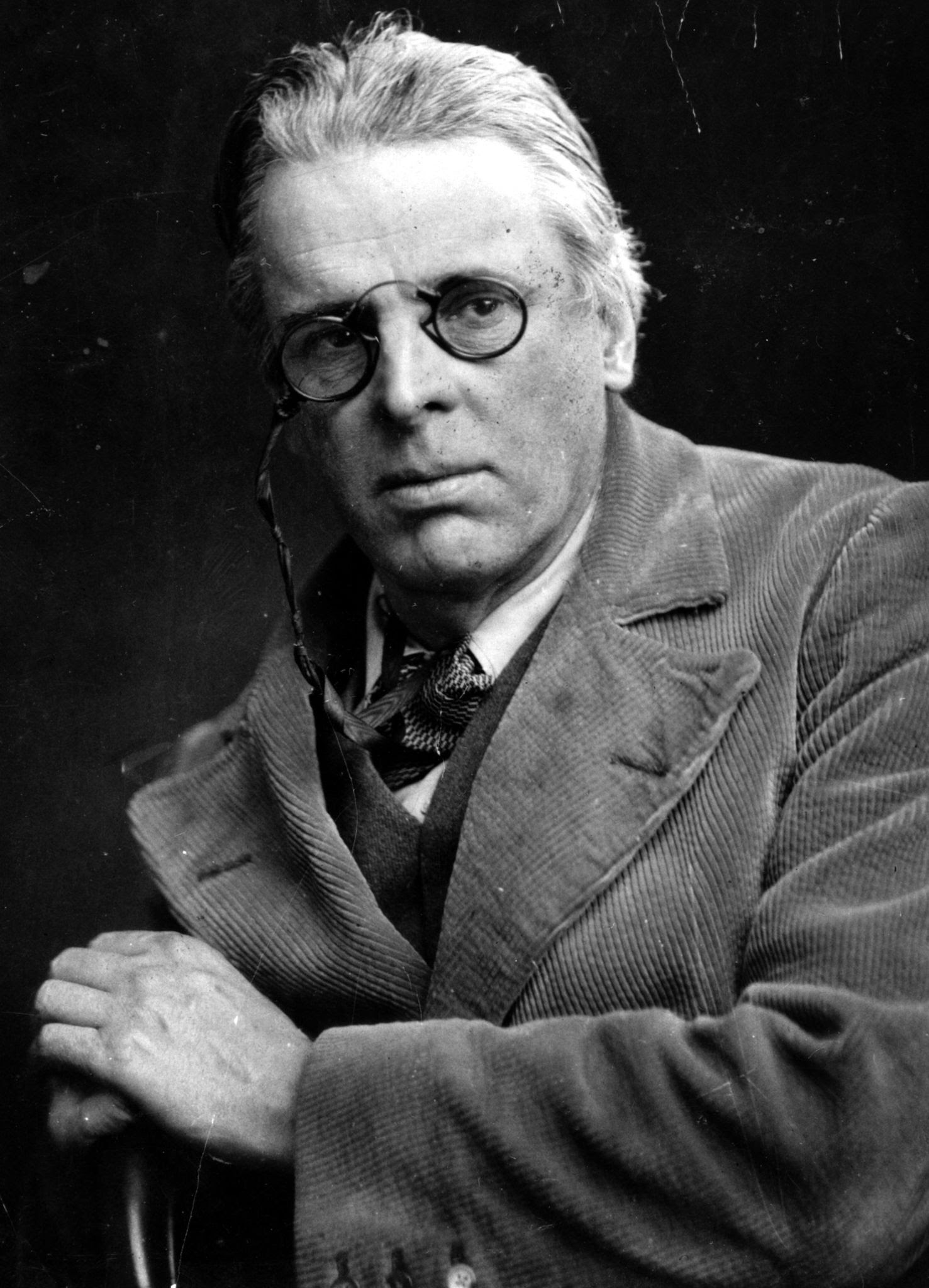

Although there was no popular call for divorce in the new state, as W.B. Yeats infamously highlighted, removing the already restrictive parliamentary route from Irish petitioners raised concerns about minority rights in the new state. Subsequent consideration of divorce was often religiously charged but, as in both Westminster and Northern Ireland, this lacked a regimented religious or party divide. Divorce was subsequently banned in the 1937 Irish constitution, and divorcees and those seeking divorce law reform were frequently lampooned by the Catholic Church as morally suspect.

Britain gradually moved towards more divorce accessibility, from parliament to the matrimonial division of regular courts. Ireland, North and South, remained reluctant, though Stormont finally passed an act in 1938. Much is made of the Free State’s ban on divorce from 1925 but, despite Senator Yeats’s famous protest, the prohibition broadly represented the values of the electorate.

There was an expectation of the inclusion of divorce in the 1922 constitution based on the principle of freedom of conscience, and Attorney General Hugh Kennedy aligned divorce with Protestantism, highlighting the nuances behind Roman Catholic Church interventions, which were sought out by W.T. Cosgrave to prevent the introduction of divorce bills. The interventions of Senator W.B. Yeats in the debates on divorce in 1925 assisted in the polarisation of positions between the minority Protestant and majority Roman Catholic population.

Yeats had been appointed to the first Irish Seanad in 1922, and was reappointed for a second term in 1925. Early in his tenure a debate on divorce arose, and Yeats viewed the issue as primarily a confrontation between the emerging Roman Catholic ethos and the Protestant minority. When the Roman Catholic Church weighed in with a blanket refusal to consider the opposing position, the Irish Times countered that a measure to outlaw divorce would alienate Protestants and ‘crystallise’ the partition of Ireland.

The Seanad’s debates clearly put Yeats in opposition, and he knew it:

‘An Cathaoirleach: The House might like to spend the rest of the day over this divorce business and if that is the universal wish of the House, the debate might be resumed. I call upon Senator Yeats.

Yeats: I speak on this question after long hesitation and with a good deal of anxiety, but it is sometimes one’s duty to come down to absolute fundamentals for the sake of the education of the people. I have no doubt whatever that there will be no divorce in this country for some time. I do not expect to influence a vote in this House. I am not speaking to this House. It is the custom of those who do address the House to speak sometimes to the reporters.’

A blacklist was made of those who voted for the motion, to be used against them when they sought re-election, and even abstention was no guarantee of safety, as those ‘hurlers on the ditch’ were derided as ‘defaulters’. Senator John Bagwell’s plaintive suggestion that ‘those who disapprove of divorce should abstain from divorce’ seemed so simple, but simplicity has never been a feature in marital conflict.

Joseph E.A. Connell Jr is the author of The Terror War: the uncomfortable truths of the Irish War of Independence (Eastwood Books, 2022).