By Jesse Harrington

In two parliamentary questions in June 2024, Clare TD Cathal Crowe called for a government task force to locate and recover the alleged crown of Brian Bóruma (Brian Boru), the Irish king mortally wounded at Clontarf in 1014. Crowe suggested that, if this crown existed, it might be found somewhere in the Vatican, and he urged the government to engage with the Holy See for its repatriation.

Historians have been rightly sceptical that any such crown will ever appear. Already in 1948 Fr Aubrey Gwynn SJ had pointed out that Irish kings did not wear crowns in Brian’s time, and thus that any such reference must reflect some later fiction. Crowns did not feature in traditional Irish expressions of inauguration nor of sovereignty, being favoured instead by kings and emperors in England, France and Germany.

It is only a century after Brian’s death that references to symbolic crown-wearing appear in Irish literature, in texts written for the kings of Munster. These include Bishop Gilbert of Limerick’s (d. 1145) De statu ecclesiae, a blueprint for the Irish church written for the Uí Briain kings, as well as Caithréim Cheallachán Chaisil, a royal saga written for their principal dynastic rival, Cormac Mac Carthaig (d. 1138). These are idealised depictions, consciously modelled on contemporary Continental and English practice. They were apparently innovative for their period, and it is not known to what extent they were followed in practice.

DONNCHAD MAC BRIAIN’S PILGRIMAGE TO ROME

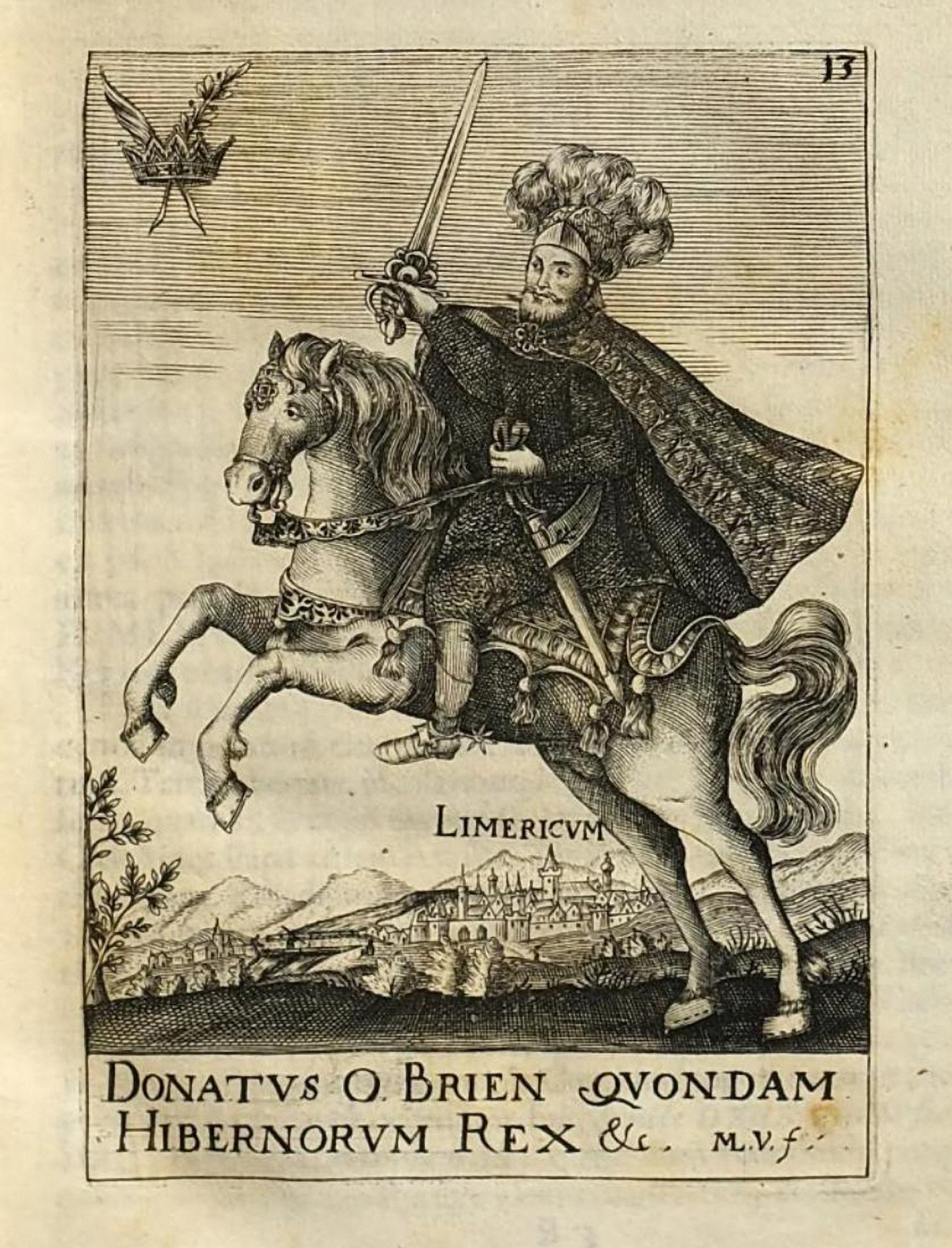

The legend of how a ‘crown of Ireland’ came to Rome dates instead from the later sixteenth century and focuses on Brian’s son, Donnchad mac Briain, who ruled Munster for five decades until his own overthrow in 1063. Then, perhaps already in his seventies or eighties, he went on pilgrimage to Rome, where he is said to have undertaken penance at ‘the monastery of St Stephen’. This probably refers to the grand basilica of S. Stefano Rotondo, situated on the Caelian Hill near an established community of Irish monks in Rome, and it was there that he would have died and been buried.

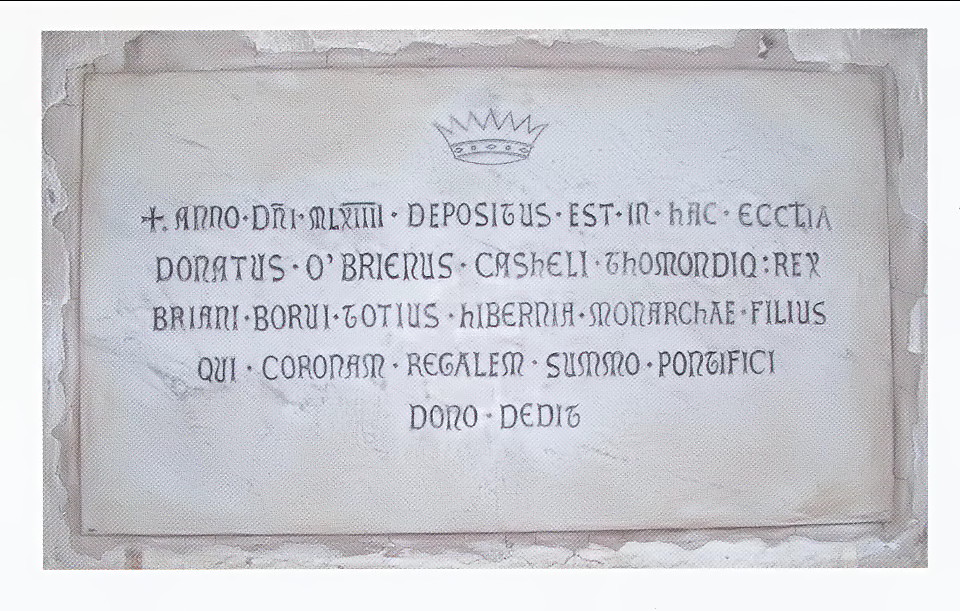

This much can easily be reconstructed from the medieval annals. In addition, a nineteenth-century commemorative plaque in S. Stefano, bearing an image of a crown, signals Donnchad’s burial there. As Denis Casey has recently argued, however, the earliest reference to a crown being brought by Donnchad to Rome appears in the later sixteenth-century bardic poetry and the seventeenth-century Annals of Clonmacnoise, which followed Henry VIII’s Crown of Ireland Act of 1542. The Act had created the new title of ‘king of Ireland’ and introduced into contemporary political discourse the idea of a crown as its symbol. According to the poems and Annals, Donnchad had surrendered this crown to the popes. The Annals were based on a medieval Irish source, but the only surviving version is Conall Mag Eochagáin’s translation into English of 1627. It has been reasonably suggested that Mag Eochagáin translated somewhat loosely, based on an understanding in the spirit of his times, supplying ‘crown’ for an Irish word that might more strictly be translated as ‘rule’ or ‘sovereignty’.

There were other early modern legends concerning Donnchad and Irish sovereignty. The Irish Catholic historian Seathrún Céitinn (Geoffrey Keating), writing in his Foras Feasa ar Éirinn in 1632, offered another version. Céitinn claimed that the nobles of Ireland, divided as to who should rule them, had in 1092 surrendered the sovereignty of Ireland to Urban II, the pope who famously launched the First Crusade. Céitinn’s account of Urban’s involvement was intended to explain the papal claim to dispose questions of Irish sovereignty during the later English invasion of 1171, as well as over the centuries down to Céitinn’s own time.

A similar political myth-making impulse appears to lie behind the story of the crown in the bardic poems and Mag Eochagáin’s Annals, which could then argue in a Catholic Reformation context that the papacy reserved the right to bestow an Irish Catholic ruler anew, so long as a physical crown had remained in Rome. Céitinn, however, placed the transfer of sovereignty three decades after Donnchad’s pilgrimage and made no mention of a crown, despite reporting other legends of the king’s adventures in Rome.

THE CROWN OF 1186

A different medieval event may offer a further interpretation of the tradition of the crown. In 1151 the senior male members of the Uí Briain dynasty were unexpectedly extinguished at the battle of Móin Mór, after which various rival dynasties vied in their place for the kingship of Ireland. The Uí Conchobair of Connacht, the Meic Lochlainn of the north and the Plantagenets of England all staked their claims over the course of the 1150s–1170s. Each attempted to co-opt the church apparatus through which the Uí Briain had supported their rule, along with other Uí Briain theories, tools and symbolic markers of kingship, which Bishop Gilbert had once proposed might include crown-wearing.

In 1176 King Henry II of England petitioned Pope Alexander III to send a crown for Ireland to confer on his son John, lord of Ireland. The pope declined to do so. Instead, Alexander sent a legate, Master Vivian, to mediate the question of Irish sovereignty. In 1185, following Ruaidrí Ua Conchobair’s abdication as king of Connacht, Henry wrote again, this time to Pope Urban III (r. 1185–7). Shortly after, a crown was brought from Rome, intended for John’s coronation. The English chronicler Roger of Howden describes a crown of gold-embroidered peacock feathers. This would have been a toufa, a plumed crown favoured by Byzantine emperors and Roman popes in twelfth-century ceremonial.

John’s coronation was perhaps intended to take place in Dublin in 1186 at Easter or Whitsun, two of the three times of the year that Bishop Gilbert had designated as suitable for crown-wearing. This event would have been preceded by John’s preparatory tour of Ireland in 1185–6 and the Lent Synod held in Dublin in 1186, which clergy from Ireland, England and Rome attended. Unfortunately for Henry, John’s tour proved a disaster. The planned coronation was shelved, and the hapless prince returned empty-handed to England. The crown later went unmentioned, presumably becoming an embarrassment for all concerned.

Could it be that this toufa crown, bestowed by Urban III on the Plantagenet lord of Ireland, lies behind Céitinn’s later story of the ‘crown’ of Irish sovereignty bestowed on Urban II by the Gaelic lords of Ireland? Urban III was not a prominent pope, reigning for less than three years, while Urban II was easily one of the most influential and best remembered of the Middle Ages. Urban II had also maintained good relations with the Uí Briain kings of Munster, who used his reformist church councils as models for their own. From a terse or misread record of the event, the two popes might easily have become confused, with a new version of events later introduced to account for the discrepancy.

- STEFANO ROTONDO

Notably, the crown of 1186, and the legate who bore it, had an indirect association with the site of Donnchad’s burial. This might have led later to a direct association being made between the twelfth-century crown and the eleventh-century king.

Historians have hitherto presumed that the crown of 1186 was brought by the papal legate Octavian, who was a cardinal-deacon in Rome. Octavian, however, never travelled to Ireland, but there is reason to believe that he was accompanied by a more senior legate who did. A Roman cleric named Gerard, who may be identified as the Burgundian cardinal Gerard d’Autun, attended Dublin’s Lent Synod on papal business. Gerard and Octavian probably travelled together to England, with Gerard continuing to Ireland as the more senior cardinal for the planned coronation, while Octavian remained behind, presumably partly to keep open the important diplomatic lines of communication between Ireland, England and Rome.

Crucially, Gerard d’Autun was cardinal-priest of S. Stefano. This same church appears to have provided no fewer than three consecutive cardinal legates to Ireland following the English invasion: Vivian (1176–7), Gerard (1185–6) and John of Salerno (1201–3). It was unusual for a single church in Rome to provide legates to a single Christian province in such close succession, which gives the pattern some significance.

Nonetheless, the fact that Gerard alone brought a crown with him from S. Stefano shows that the crown itself is unlikely to have been the principal reason why this church’s cardinals were chosen for these important missions to Ireland. Instead, it seems that S. Stefano had gained important Irish associations that made it pragmatically useful to those missions. One reason might have been the church’s proximity to Rome’s Irish monastic community, which appears to have been concentrated at S. Trinitas Scottorum (‘Holy Trinity of the Gaels’). Another reason may have been the reputed burial of Donnchad within the basilica, making S. Stefano a pilgrimage site of special relevance for the Irish in Rome, and especially appropriate to the question of Irish sovereignty. These associations may have made it seem plausible to successive popes that cardinals sent from the basilica would be well received in Ireland.

In short, in the century or so after Donnchad’s death, S. Stefano had gained sufficient associations with Irish pilgrims, monks and royalty to make it appropriate for a crown to be carried to Ireland by the cardinal who served as that church’s custodian. Later commentators, and perhaps even those who had intended to promote the aborted coronation of 1186, might have identified that invented crown as that of Donnchad himself, hoping to lend an aura of tradition to proceedings. Reports of the event may have survived as a somewhat garbled tradition into the sixteenth century, to be revived and reforged as suited to contemporary political needs. Thus the twelfth century’s historical connections of S. Stefano, Donnchad and Urban III transformed into the more mythical associations of S. Stefano, Donnchad and Urban II.

LOST FUTURES AND UNDYING PASTS

Ireland was not unique in being granted a peacock crown for a reign that was never realised as intended. A royal leaf crown with peacock feathers may have formed part of the iconography of Duke Frederick II of Austria in 1245, in preparation for a kingdom of Austria that similarly never materialised. Frederick died in battle the following year, without male heirs, and was the last of his ducal line. His crown, or one inspired by it, may have been appropriated by his later Habsburg successors for ceremonial occasions but, if it was, it does not survive.

Likewise, there is no record of what happened later to the plumed crown of 1186, whether in Rome or England. In either location it is unlikely to have survived, never having been used for its intended purpose. Nonetheless, a surprising echo occurs in the seventeenth century. In his Compendium of the history of Catholic Ireland, Philip O’Sullivan Beare reported the arrival of papal and Spanish legates in 1600. These accompanied the archbishop of Dublin into Ulster and brought with them from Rome ‘a plume of phoenix feathers’ with which to crown Hugh O’Neill of Tyrone for his military efforts against Elizabeth I of England.

This event followed earlier claims made on behalf of Hugh O’Neill’s grandfather, Conn Ó Néill (d. 1559), to the Uí Briain crown believed to have been brought to Rome centuries earlier. There could have been little doubt about what the plume represented. The peacock-feathered crown of 1186 was known from Raphael Holinshed’s influential Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland, first published in London in 1577. Plumed crowns additionally featured on the Tudors’ royal heraldic badges, such as in the three ostrich feathers that adorn the Prince of Wales’s Feathers to this day. As a Munster lord, O’Sullivan Beare would have been loath to acknowledge a northern lord as a crowned superior and is thus unlikely to have invented Hugh O’Neill’s plume. There is nothing to suggest that the crown of 1186 and the plume of 1600 were one and the same, but the visual language and symbolism are very much of a piece with the peacock crown and with the revived Gaelic kingdom that the phoenix represented.

In 1616, after the Flight of the Earls, O’Neill died an exile and was buried in Rome, as Donnchad had been five centuries earlier. No other mention of his plume has come to light. In any case, the survival or otherwise of either crown may be beside the point. In the Christian iconographic tradition that adorned the basilicas of Rome, the peacock was associated with the immortality of Christ and his undying martyrs. The phoenix, likewise, was a classical symbol of longevity and perpetual rebirth. In this sense, by the end of the Middle Ages the peacock feathers that had embroidered the crown of 1186 had arguably been reborn as a symbol of something that Henry II did not intend: an undying memory of Uí Briain rule in Ireland.

Jesse Harrington is a research fellow at the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies and has been a visiting researcher at the Norwegian Institute in Rome.

Further reading

D. Casey, ‘A man of no mean standing: the career and legacy of Donnchad mac Briain (d. 1064)’, Peritia 30 (2019), 29–57.

J.P. Harrington, ‘S. Stefano al Monte Celio, Donnchad mac Briain, and papal legates in Ireland, 1064–1203’, Irish Historical Studies 48 (173) (2024).

P.W. Lehmann, ‘Theodosius or Justinian? A Renaissance drawing of a Byzantine rider’, Art Bulletin 41 (1) (1959), 39–57.

B. Ó Buachalla, The crown of Ireland (Galway, 2006).