By Tim Carey

One of the best-known images of Dublin’s mid-twentieth-century cultural life is a cartoon called Dublin Culture. In it are nearly 40 people—all men—in the back room of the Palace Bar on Dublin’s Fleet Street. Among the tables and drinks there is a unique generation of journalists, writers and artists: Flann O’Brien is at the back of the room, looking slightly dazed; the almost child-sized painter Harry Kernoff is sitting at the front; there are writers Austin Clarke and Patrick Kavanagh, who seems to be about to leave (he was reportedly never happy in the Palace), painter Seán O’Sullivan, sculptor Jerome Connor and journalist Cathal O’Shannon. In the middle of this who’s who of the Dublin scene is the now-legendary Irish Times editor Bertie Smyllie, holding court. And in the front left is the bearded figure of Alan Reeve, the artist of this eclectic gathering. Dublin Culture was described by one contemporary as a ‘remarkable essay in pictorial criticism’. Since it was drawn it has featured in works about this era of Dublin’s history and the biographies of many of those featured.

The first time I came across the cartoon was in Costello and Van de Kamp’s biography of Flann O’Brien, but it kept cropping up whenever I read about that time in Dublin or about one of the people depicted. The most that was ever said about the cartoonist was his name and that he was from New Zealand. It had always seemed strange that Alan Reeve should remain almost anonymous. When I wrote my book Dublin since 1922 in 2016, I included more information about Reeve than had been provided previously but it was still scant. It continued to bother me that I knew so little about him.

Then a random social media post that I made about the cartoon led to a response from a niece of Alan Reeve and a suggestion from her to contact the New Zealand National Library. A scan of the online catalogue did not seem promising—it mainly seemed to hold material that I already had—so I left it. Then one idle evening I chanced sending an email to the Library to ask whether they had any additional information not in the catalogue. Shortly afterwards I received a reply from the brilliantly titled ‘Curator of Comics and Cartoons’, in which he said that a search of uncatalogued material had revealed albums that charted Reeve’s life in photographs, drawings and brief narratives from his birth in 1910 to just months before his death in 1962. Finally, the story of the person behind Dublin Culture could be told.

Born into a middle-class family in Wellington, Alan Reeve attended Wellington College before briefly pursuing careers in architecture and advertising. Art, however, was his true calling. In his late teens he founded the ‘New Zealand Amateur Arts and Literature Association’, into which he poured his energies. In 1933, at the age of 22, he held his first caricature exhibition, featuring notable Wellingtonians. In March 1934 he went to Australia for three years, where he made what he described as an ‘up-and-down living’ from the proceeds of the caricatures that he drew. He then headed off to Europe to see how far his skill would get him.

Arriving in Rapallo, Italy, he soon became friends with writer Ezra Pound and lived on the Riviera, selling caricatures in Monte Carlo’s Paris Hotel and then Marseilles. In March 1938 Reeve moved on to London, where he sold caricatures to various publications, including the Radio Times, worked in nightclubs sketching revellers, and in June 1939 put on an exhibition of his work. He found making a living there difficult, however, and shortly after the outbreak of the Second World War he decided to make his way home to New Zealand, starting with an intended three-month stay in Dublin.

The distinctive tall, red-haired New Zealander, now sporting a fine beard—a rarity in Dublin at the time—arrived with just £2.10 to his name, but the city proved to be very receptive to him and his talent. For Reeve his time in Dublin would always hold a special place.

He soon found himself in what was one of Dublin’s most interesting of cultural circles, usually found in the back room of the Palace Bar. It was here that he most likely met Bertie Smyllie, who commissioned him to produce a weekly Saturday cartoon series called ‘Drawing the Crowd’, which began on 25 November 1939. In his flat at 52 Merrion Square Reeve drew 34 of the great and the good, including theatre figures Hilton Edwards and Lennox Robinson, journalist Cathal O’Shannon, artists John Lavery, William Conor and Paul Henry, politicians Alfie Byrne and Erskine Childers, and writer Maurice Walsh, as well as the now more obscure Frederick Summerfield, ‘motor trade leader, industrialist, rotarian and golfer’, and J. Bronte Gatenby, Professor of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy in Trinity College.

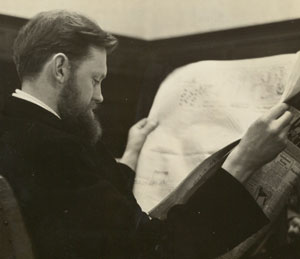

With his striking appearance, unusual accent and newspaper cartoons, Reeve became well known on the Dublin scene and was photographed attending exhibition openings and the Baldoyle races, was drawn by artist Harry Kernoff, gave talks to the likes of the Rotary Club, was interviewed on Radio Éireann, and was featured in several newspaper articles. In the archive is a photo of Reeve sitting comfortably in the Palace’s back room, appropriately reading the Irish Times. One newspaper article said that he had made hundreds of friends in Dublin; another simply stated that ‘to know Reeve is to like him, a lot’.

While all of his Dublin drawings were of men, it’s evident from a number of photographs that Reeve enjoyed the company of many Dublin women, including sisters Brenda and Ingrid MacDermot, Betty Aitken and Betty Dolan—a beautiful photograph of the two of them possibly suggests an intimacy deeper than friendship.

In June 1940, eight months after arriving for his intended three-month stay, Reeve left for America. Before taking his leave, he held an exhibition of drawings in Brown Thomas’s on Grafton Street. The exhibition was regarded as one of the most successful held in Dublin and sales not only funded Reeve’s trip across the Atlantic but also left him with $200 dollars to spare. Featuring nearly 80 drawings, the centrepiece was Dublin Culture. In the archive Reeve describes it as a ‘Group of Artists and Intellectuals and Old Cods in the Palace Bar’, but it was immediately regarded as an important work—‘the picture is worthy of preservation as a record of our times’, wrote one journalist, while another wrote of ‘the gravity and solemnity with which the group of poets, painters, playwrights, journalists attack the business in hand, obviously exchanging ideas of profound might and substance, to the music of clinking glasses’.

Strangely, despite the interest, it was one of the few pieces that did not sell on the night. For a time the drawing was displayed in the window of Combridge’s Gallery on Grafton Street. Although it is not recorded exactly when or how, Dublin Culture eventually found its way to its natural home, the Palace Bar, where it still hangs today in the back room.

One historical footnote is worth noting. When Dublin Culture is referenced, it is usually stated that it was first published in the Irish Times in 1940. This does not seem to be the case. Repeated searches of the Irish Times archive and a query sent to the paper have failed to find it published in 1940, except in the background of a photograph from the exhibition opening. It did not appear in full in the Irish Times until March 1953. In fact, its first publication was in early 1941, in the arts journal A-D, published in New York, where Reeve had arrived from Dublin a few months earlier.

The hundreds of photographs in the archive provide a wealth of information about the man who produced Dublin Culture and make it clear that Reeve’s time in Dublin was his most successful. And it is also clear that in Dublin Culture he has achieved what every artist desires—for their work to stand the test of time.

Tim Carey is the author of Dublin since 1922 (Hachette Books, 2016).