ROB GOODBODY

Wordwell Books in association with Dublin City Council

€17.99

ISBN 9781916742130

Reviewed by

John Gibney

John Gibney is Assistant Editor with the Royal Irish Academy’s Documents on Irish Foreign Policy series and worked as a tour guide in Dublin for fifteen years.

It sometimes feels that a proper consideration of Ireland’s industrial heritage can be pushed to one side by various factors. There have been some major surveys (notably by Colin Rynne), but the reality that most of Ireland’s heavy industries were clustered in the north-east before and after partition perhaps feeds the assumption that there was no industry of note elsewhere on the island. There was nothing comparable, admittedly, but that isn’t the same thing. Industrial heritage hasn’t been somehow ‘airbrushed’ out of Irish history but it certainly feels overlooked, even as its physical presence remains all around us. Take the multiple instalments of the Irish Historic Towns Atlas (IHTA): its mapping of Irish urban environments amply illustrates the footprint of industries in the towns it covers. It is probably unsurprising that one of the IHTA atlases of Dublin was written by Rob Goodbody.

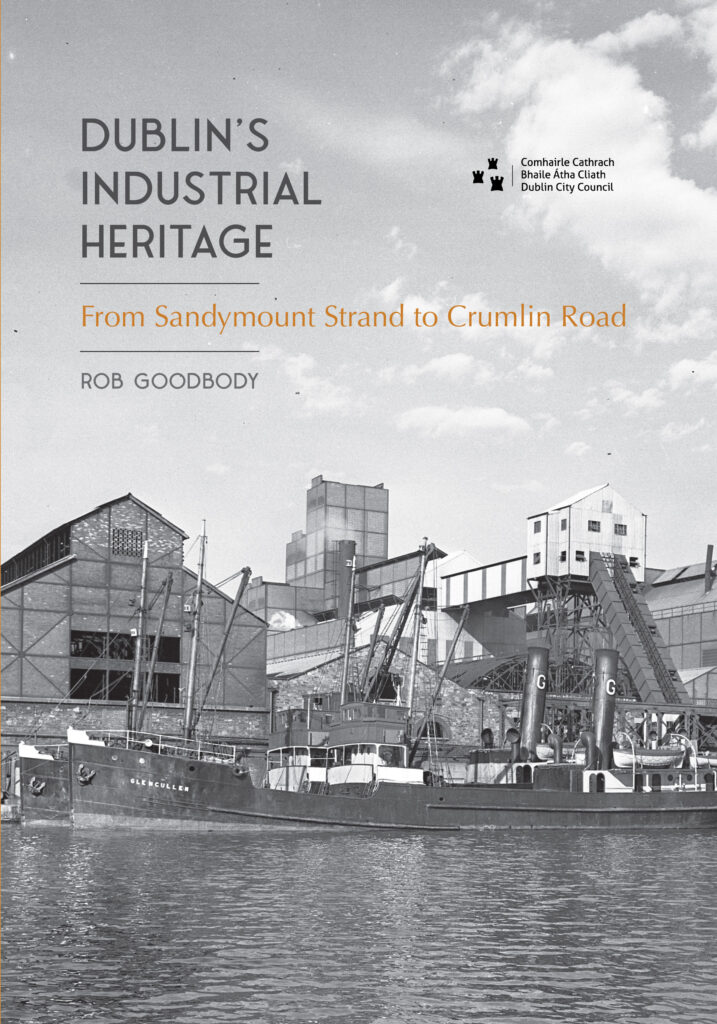

Prompted by the Dublin City Industrial Heritage Record, this book is the first of a projected trilogy and covers a broad sweep of Dublin city south of the River Liffey. This is a handsome and well-illustrated volume, sturdily made, as befits what will surely be used ‘in the field’ as a work of reference to be dipped into repeatedly. It is lively, well written and clearly structured, covering far more than the title might suggest.

Underpinning Goodbody’s book is a very broad view of what industrial heritage consists of, and it is all the better for it; one might define it as incorporating labour-intensive occupations that were industries in their own right, as well as feeding into and facilitating more familiar and visible industrial endeavours—cases in point being the production and processing of raw materials as much as what was eventually made from them. The book has a roughly chronological structure, beginning with the oldest industrial activities that can be traced in the city and ranging widely in time within the space that is its subject-matter. It is also illuminating on what was previously to be found in the city, as much as on what has been built over since, as Goodbody does not confine himself to what is still visible in Dublin. Who knew that in 1751 a quarry was operating at the junction of what is now modern-day Baggot Street and Fitzwilliam Place, making good use of Dublin’s calp limestone?

Goodbody has arranged his book thematically, with chapters dedicated to distinct categories, from geology and land reclamation to light and heavy industries (such as food-processing and shipbuilding respectively), along with the infrastructure of communications and utilities, and finally military installations. It gives a fresh perspective on the history of Dublin, one that is firmly located within the physicality of its urban environment. A particular strength is its alertness to even minor features still embedded in the Dublin streetscape. For example, if one stood outside a Georgian house in the city, alongside its architectural finery one might still see adjacent coal-hole covers on the pavement outside. Who made them? And where did the stone from which the house was built come from? Equally, the River Liffey looms large, from land reclamation on the south quays to its shipbuilding heritage, and it is explored in terms of such diverse features as the traces of major infrastructure around Grand Canal Docks and long-vanished rope-walks. The latter are described here as ‘a linear space somewhat longer than the length of rope being manufactured’; by their nature they are readily visible on older maps and point to the ancillary industries associated with the docks.

Taken as a whole, the book gives a holistic overview of its subject. Industry permeated Dublin: from quarries and brickworks to breweries and ironworks, to trains and even the products stocked in shops. There are plenty of flashes of what has been lost or superseded: a 1956 aerial photo of the Greenmount Spinning Mill at Harold’s Cross reveals a substantial and surprisingly elegant premises, now replaced by a business park. This might be emblematic of change, as the nature of economic activity in inner-city Dublin has inevitably shifted, but industrial heritage continues to evolve. Infrastructure continues to be constructed (eventually!). Dublin Port is still in operation (and has invested in its own heritage in recent years). To take the docklands south of the Liffey as another example, the older industries clustered there have been replaced by occupations like finance and tech, but the architectural features that these have thrown up, like Google’s premises on Barrow Street, might well qualify for inclusion in a future edition of this series. The same is surely true of the clusters of light industry and manufacturing that have emerged around the M50.

In short, this is an excellent short history of Dublin through the lens of industry and, as such, offers a fresh and invaluable perspective on the story of the capital. It also highlights Dublin City Council’s laudable commitment to investigating, recording and communicating the city’s heritage, as shown in multiple initiatives in recent years. While not every local authority will have access to the same resources, given differences in size and population, projects and publications such as this could be embarked on for virtually every county. In the meantime, this book should be essential reading for anyone interested in the history of Ireland’s capital city.