By Tim Ellis-Dale

On 2 May 1945 the streets of Monkstown, Co. Dublin, bore witness to the spectacle of Taoiseach Éamon de Valera entering Gortleitragh, a comfortable, if not overly grandiose, Victorian villa. From 1932 to 1936 it had been the residence of Domhnall Ua Buachalla, the last governor-general of the Irish Free State, but in 1937 it became the home of Eduard Hempel, the minister of Nazi Germany to the Irish state. De Valera’s visit to Hempel in May 1945 was an infamous one, its purpose being to offer condolences on the death of Adolf Hitler two days earlier. The visit was naturally widely condemned in the international press. What is also interesting, however, is the wave of extremely critical letters that de Valera received from across the world (but particularly from Irish-Americans) in the following days and weeks, some of which condemned his visit in very explicit terms. This fascinating body of sources (available in the de Valera papers in the archives of University College Dublin) highlights the complexity of de Valera’s relationship with the policy of neutrality and the Irish diaspora.

NEUTRAL ON THE ALLIED SIDE?

De Valera’s visit should be understood in the context of Irish neutrality during the Emergency (the euphemistic term applied by the state during the conflict). Ireland was one of a small handful of states (along with Sweden, Switzerland, Spain and Portugal) which did not declare war at any point during the conflict, were not invaded and did not take part in any form of military engagement. Nonetheless, the extent of the neutrality of the Irish state continues to be much debated by both historians and the wider public. In some respects, the state adhered to its policy of neutrality quite rigidly: during the conflict, Frank Aiken, as minister for the co-ordination of defensive measures, presided over a censorship regime that forbade newspapers from making any comment that could be construed in any way as partial to either side in the conflict. Moreover, throughout the conflict the state maintained diplomatic relations with both Allied and Axis powers. Yet an argument might be made that the state was discreetly slightly more partial to the Allies: Allied airmen who landed in the neutral Irish state were returned to Northern Ireland, while Axis servicemen who landed were interned for the duration of the conflict. This approach might be explained by the fact that de Valera gave assurances to the British government that the neutral Irish state would not be used as an Axis base for the invasion of the United Kingdom.

In another respect, however, de Valera can be argued to have shown partiality to the Axis powers, particularly in making his notorious visit to Hempel on 2 May 1945. The reasons for this visit are controversial. The official justification given by de Valera at the time was that, ‘so long as we retained our diplomatic relations with Germany, to have failed to call upon the German representative would have been an act of unpardonable discourtesy to the German nation and to Dr Hempel’. Nonetheless, critics have noted that a similar undertaking was not made to the American minister, David Gray, upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt on 12 April. For instance, one Irish-American, a Mary Mullaney, wrote to de Valera following the visit to Hempel to ask ‘if you made a personal call at the American Embassy upon the death of the grandest man of our time, our beloved and universally respected President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’. In fairness, tributes were paid to the president in the Oireachtas the following day, with de Valera declaring that ‘President Roosevelt will go down to history as one of the greatest of a long line of American Presidents’.

While it would be grossly unfair to suggest that there was any ideological partiality towards Nazi Germany on de Valera’s part, it is probably reasonable to suggest that on a personal level de Valera and Hempel enjoyed a good relationship. The Axis powers were, overall, largely content with the Irish state’s policy of neutrality and did not attempt to persuade or pressure the state to jettison it, as the Allied powers did. It is worth noting that de Valera’s relationship with David Gray was much more difficult. These difficulties came to a head in February 1944 with the ‘American note’ controversy, wherein Gray demanded the removal of Axis diplomatic representatives from Ireland. In comparison, de Valera and Hempel had a relationship that was at least cordial. Until Hempel’s death in 1972, the men sent each other Christmas cards every year. Indeed, in 2011 Hempel’s daughter suggested that de Valera’s visit largely happened ‘out of friendship … He visited because he knew my father, and the condolences were to my father because his position [as envoy to Ireland] was finished.’

In any case, de Valera’s visit to Hempel was widely condemned outside Ireland, particularly in the United States. De Valera’s relationship with the United States was a deeply complex one. In one respect his birth there and linkage to the Irish-American community was a source of strength. During his lifetime he made numerous visits to the US, in many cases for fund-raising purposes, most notably in 1919–20. He exerted a highly emotive influence over the Irish diaspora and often received correspondence from ardent supporters and admirers. A young Irish student in the United Kingdom wrote to de Valera in 1937, declaring that ‘I am one of your strongest supporters. I consider you as the finest leader Ireland has had yet … I have a picture of you in my room, it is taken from a journal, and I have had it framed.’

Yet it is also fair to say that this relationship with the diaspora was a source of difficulty for de Valera. The circumstances of his birth in New York City were and remain hugely controversial: no birth, marriage or death certificate belonging to his Spanish (or possibly Cuban) father, Juan Vivion de Valera, has ever been located. (See ‘Éamon de Valera’s mother-and-baby home’ in HI 31.5, Sept./Oct. 2023, pp 38–42.) His birth to a non-Irish father was occasionally the source of mockery and rebuke in Ireland. Indeed, during a debate on neutrality in the Dáil, Fine Gael’s John Dillon remarked that ‘My ancestors fought for Ireland down the centuries on the continent of Europe while yours were banging banjos and bartering budgies in the backstreets of Barcelona’. Nor did de Valera enjoy unanimous support among leading members of the Irish diaspora. During his 1919–20 tour of the United States he came into conflict with Daniel Colohan and the veteran Fenian John Devoy. In 1922 Devoy backed the Anglo-Irish Treaty, in opposition to de Valera’s stance, with the former even referring to the latter as ‘a Jewish b-stard’. This anti-Semitic abuse, which was occasionally directed at de Valera by his political opponents, arose largely out of suspicions about the circumstances of his birth.

HATE MAIL

While Irish-America was supportive of de Valera’s neutrality policy (which was aided by the fact that the USA was officially neutral until December 1941), it was also the case that many Irish-Americans served on the Allied side in the US armed services. Following the notorious visit to the German legation, one Caroline Burchell wrote to de Valera on 22 May 1945, remarking that ‘It’s very obvious you didn’t stop to think of the number of American boys of Irish extraction who’ve lost their lives fighting a war this fiend [Hitler] started’. Several Irish-Americans wrote similar missives. Similarly, an Irish-American serviceman stationed in the Philippines wrote exasperatedly: ‘You well know how many Irish boys are fighting and have died in this war … I have a mother in Ireland, I also have brothers fighting this war, but I guess Dr Hempel means more to you—maybe he’s a nice fellow … Have no more time, got to fight the Jap.’

Many of the Irish-Americans who wrote to de Valera expressed a sense of profound disbelief and disillusionment. For one Mary McGreevy, it was difficult ‘to express the regard in which I have always held the name of Eamon de Valera … It was therefore a source of great embarrassment to us, the descendants of Irish immigrants to have you—the Prime Minister of Eire [sic]—express regret at the cessation of existence of the man who caused us so much sorrow.’ Similarly, a Charles C. Thompson, based in California, felt ‘ashamed to be an Irishman when we have such men as yourself representing the Irish people … For any white man speaking the English language to act as you have done is a disgrace …’ The racial overtones of this letter were matched by an Angela Walsh, who expressed the belief that it was time he ‘stepped out of the picture and gave a real Irishman a chance’, a possible reference to de Valera’s parentage.

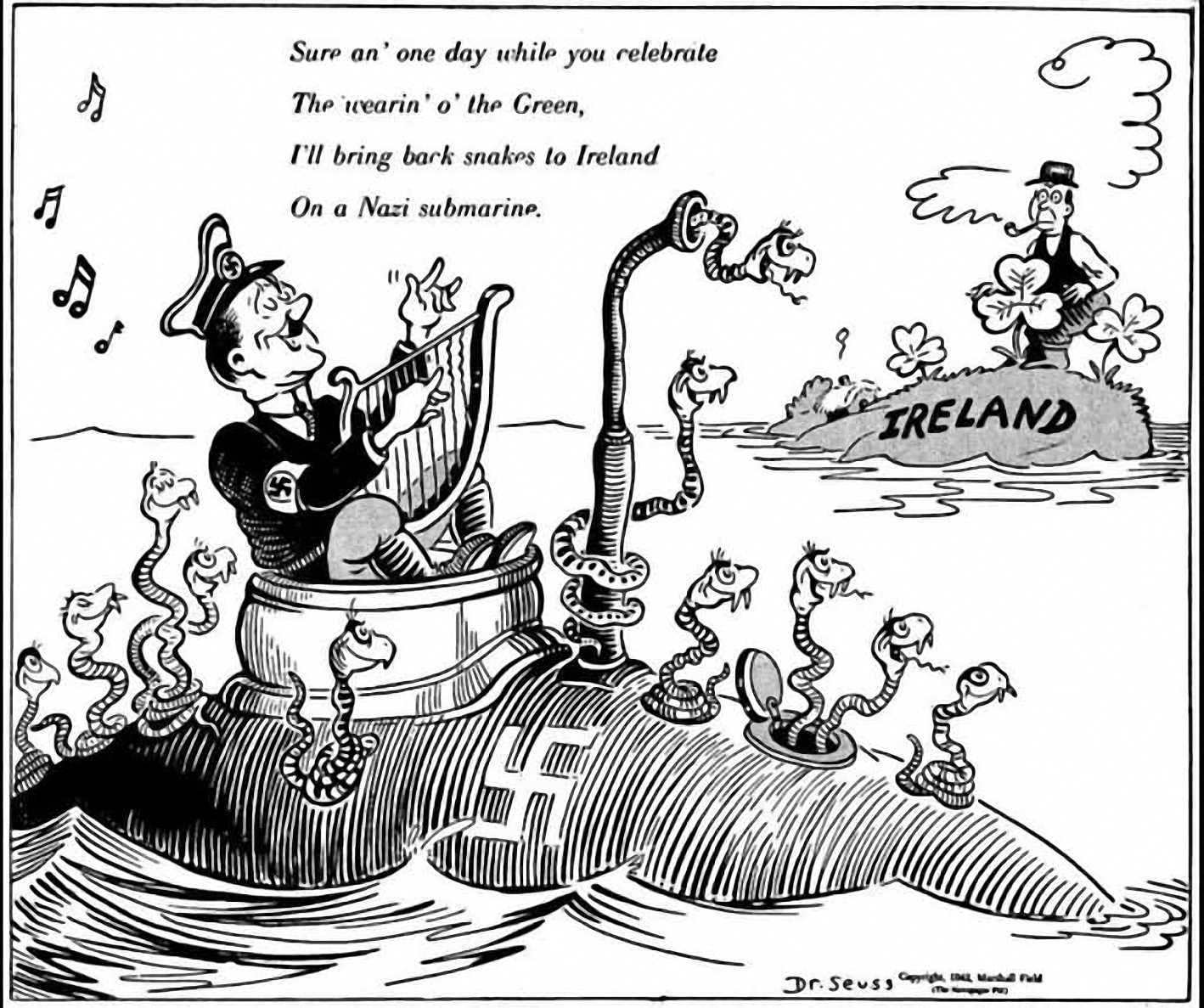

Some letters were even more explicit, with one anonymous correspondent declaring: ‘You are so low, you would not have to get on your knees to kiss the ass of a potato bug’. Letters from a James B. O’Leary and Jane O’Callaghan went so far as to call de Valera ‘a son of a bitch’ (again a possible reference to the circumstances of his birth and parentage). Perhaps one of the most vehemently critical letters came from a Mary Murphy of Brooklyn, New York: ‘St Patrick chased the snakes out of Ireland many years ago—but you’re one he overlooked. I wish I were near you right now. You dog—too bad your friends—the rats you expressed so much condolences for. The Irish people should tar and feather you—you dirty bum … Hoping to read about your own healthy end before long.’

DEV’S REBUKE OF CHURCHILL

Perhaps what is most striking about these letters to de Valera is the contrasting response he received several weeks later to his famous speech rebuking Winston Churchill for remarks made on 16 May 1945 on Irish neutrality. It is worth questioning whether de Valera’s rebuke to Churchill was indeed motivated by a desire to ‘set the record straight’, given the fact that Churchill argued that the British government allowed de Valera’s government to ‘frolic with the Germans and later with the Japanese representatives to their heart’s content’. De Valera’s response was markedly restrained, prefacing his speech with the declaration that ‘I shall strive not to be guilty of adding any fuel to the flames of hatred and passion which, if continued to be fed, promise to burn up whatever is left by the war of decent human feeling in Europe’. In response, he received a tranche of glowing letters, on this occasion mostly from correspondents on the island of Ireland. A Revd Anthony in California congratulated de Valera on his ‘strong stand, Christian forbearance, and magnificent reply to Prime Minister Winston Churchill’, while the executive officers of the American County Leitrim Club observed that ‘your scholarly dignified and devastating answer to the charges made recently against you and your people was received with universal approval by the millions of Irish blooded people in America’.

Ultimately, de Valera’s visit to Eduard Hempel is difficult to defend today, though it is explicable when we consider his own position and policies vis-à-vis Irish neutrality. That the visit should have generated such a negative response is indeed understandable. What is remarkable, however, is the extent to which significant numbers of the Irish diaspora felt able to write directly (and in some cases quite explicitly) to de Valera to express their thoughts. While the sheer variety of responses to de Valera highlights the complexities of his relationship with the diaspora, the extent of these responses also reveals how closely de Valera’s own political career was tied to this community.

Tim Ellis-Dale is a Senior Lecturer in History at Teesside University.

Further reading

J.P. Duggan, Neutral Ireland and the Third Reich (Dublin, 1985).

T. Ryle Dwyer, Irish neutrality and the USA, 1939–47 (Dublin, 1977).

B. Girvin, The Emergency: neutral Ireland, 1939–45 (London, 2006).

C. Wills, That neutral island: a cultural history of Ireland during the Second World War (London, 2007).