Marginal notes on manuscripts shed light on the life of an Anglo-Norman lord and his relationship with his scribes.

By Timothy O’Neill

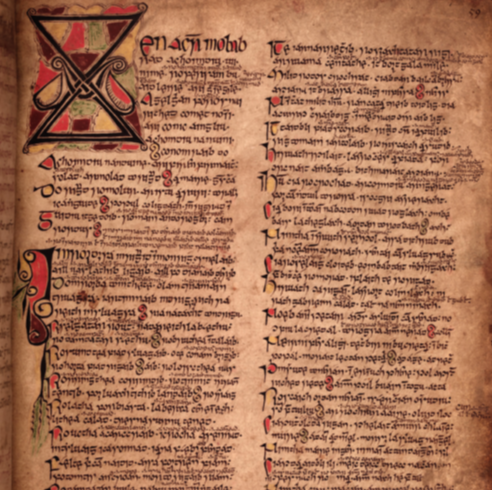

Night is falling on 21 December 1453, and in a castle in County Kilkenny a scribe peruses his manuscript. He writes a note about the heavy rain outside and his hope that his master’s son may soon be safely home. The scribe is Gilla na Naem mac Aedagáin and, with fellow scribe Seán Buidhi Ó Cléirigh, he has been transcribing texts for Edmund MacRichard Butler, adding sections to a manuscript that his patron inherited from his uncle, James Butler, the White Earl of Ormond. The material they have been copying is in the Irish language; some of it is of a religious nature, more is historical and genealogical. The texts are typical of many later medieval Irish manuscripts, but what makes this compilation special is that an Anglo-Norman lord has commissioned it and that he closely supervises the work. Judging by the unique series of 100 or so marginal notes, the patron seems to have developed a remarkably close relationship with his scribes.

Minimal privacy

MacRichard’s army was campaigning in late 1454, according to a report from his scribe who was embedded in the war party:

‘The year of the Lord this present Christmas is one thousand four hundred and fifty four, and we could tell much of the goodness of the owner of this book but that he does not wish to allow us to set it down. Nevertheless I cannot but tell of the hosting he made into Uí Peilme [Co. Carlow], for we were there for eight days and eight nights in despite of the Leinstermen. And my reason for mentioning this, beyond every rout and hosting and all the castles he has taken, is that I was with him there on this hosting, and the amount of wine and meat and whiskey and every good cheer that I got there as I lay with my lord.’

In the castles of the time there was minimal privacy and it appears that lord and scribes regularly shared accommodation, and not just while on campaign. In another note the scribe writes that Edmund sleeps long, and elsewhere that he is worried because MacRichard is sleeping in front of a draughty window. The lord seems to have shared the company of his scribes at table, as one of them comments on his late arrival for the evening meal: ‘I think it long for Edmund to be out in the frost while I wait for him without my dinner’.

The castle that MacRichard built for himself at Pottlerath near Callan, Co. Kilkenny, seems to have been a relatively comfortable place, distinguished from the ‘desolate places’ where much of the book was written. The scribe comments on the good wine and on his hopes of spending Christmas there. Nevertheless, despite their closeness, the patron made his scribes earn their keep. They sometimes had to write by candlelight, and they complain several times of being forced to work on Sundays, writing and colouring for him.

Land in Kilkenny, Waterford and Carlow

Edmund MacRichard appears in the surviving records for the first time in 1440, when the White Earl granted him the castle and manor of Polestown, in the strategically important eastern borders of the Butler lordship. In the following years MacRichard acted as the earl’s deputy and was rewarded for loyal service with land grants in Kilkenny, Waterford and Carlow. In typical medieval fashion, he and his entourage frequently moved between properties, as it was often easier to go to where provisions were rather than have supplies transported to some central location.

MacRichard traversed his territory, as the accompanying scribes recorded in a marginal note:

‘Today is the Saturday after Christmas and we are in Pottlerath after writing all that we found collected in the Psalter of Cashel … and all the new writing in this book was written for Edmund … in Pottlerath, and more of it in Kilkenny in his own court, and some of it in Dunmore and more of it in Gowran and the rest in Carrick …’

The latter is Carrick-on-Suir, where Edmund’s castle still stands on the bank of the river. Another note jotted down in August 1453 records that in the previous year Edmund built the castle at Buolick, near Urlingford in north Tipperary.

The Butler lordship was extensive, and because of the unsettled times MacRichard had to be ever ready to deploy his forces to defend the long frontier. In 1443, with his brother-in-law, the new leader of the O’Carrolls, he routed a force of O’Mores, MacGillapatricks and others who invaded Butler territory. In December 1454, as the scribe wrote, he was on the offensive in Carlow, and in October 1455 it was reported that MacRichard, his son James and James’s father-in-law, Mac Murrough, king of Leinster, ‘with banners displayed have ridden, burnt and destroyed the county of Wexford for four days and four nights’.

Wars of the Roses

From 1452 MacRichard continued as deputy for the 5th earl, who spent much of his time in England, where the Wars of the Roses had begun in 1455. Though the Butlers firmly supported the Lancastrian side, Ireland was not drawn into the conflict until after the battle of Towton in March 1461, where James, the 5th earl, was captured, and beheaded a few weeks later. He was succeeded by his brother John, who arrived in Ireland in the winter of 1461 to gather supporters for the Lancastrians, chief of whom was Edmund MacRichard. The earl appears to have gone back to England in 1462, returning that summer with what the Annals of the Four Masters called ‘a great number of Saxons’.

The earl and MacRichard captured Gerald, son of the Yorkist earl of Desmond, and took Waterford city. It was then decided to fight a pitched battle, and the site agreed was Piltown, about ten miles upriver from Waterford. It was convenient to both parties, as Desmond’s land came to the south bank of the nearby Suir and Butler’s territories stretched away to the west and north. John, earl of Ormond, however, would not fight on the chosen day, as it was a Monday, generally regarded as unlucky, but MacRichard had no such qualms and gathered his forces. Apparently, about 5,000 men fought that day and, by evening, MacRichard’s army had been defeated and he himself taken prisoner.

Books as ransom

The victor was Thomas fitz James FitzGerald, who succeeded his 80-year-old father as 8th earl of Desmond shortly afterwards. According to the Annals, Thomas was learned in Latin, English and Irish, and it was he who, as a scribe noted, demanded as ransom for his captive two books: ‘… this book and the Book of Carrick were taken in ransom for MacRichard. And it was MacRichard who had these books written for himself, and Thomas earl of Desmond captured them.’ Desmond’s centre of administration was the castle of Askeaton, Co. Limerick, which had only recently been enlarged and improved with the construction of a very fine banqueting hall, and hopefully Edmund was as well cared for as his manuscript while in Desmond’s hands.

The book was in Askeaton during the earldom of Maurice, son of Thomas, between 1487 and 1520, when a scribe from the learned family of Ó Maoil Chonaire restored some worn parts. It appears to have made its way back into Butler hands, according to a note of 1591, and presumably was collected by Sir George Carew, Queen Elizabeth’s lord president of Munster, soon afterwards. The manuscript was acquired from Carew’s son by Archbishop Laud and presented to the Bodleian Library, Oxford, in 1636, where it is catalogued as Laud Misc. 610.

MacRichard, the warrior and friend of scribes, died in 1464, the year in which his scholarly captor, Earl Thomas, founded a college in Youghal, Co. Cork. Thomas himself fell foul of the English lord deputy, Tiptoft, who, to the amazement of many in Ireland, arrested and

executed him in February 1468.

Meanwhile . . .

As they celebrated Christmas in Kilkenny in 1453, neither lord nor scribes suspected that a momentous enterprise was taking place in a workshop in Mainz in Germany. There, quietly, Johann Gutenberg and his team of printers were producing the pages, each with 42 lines of lettering, of what was to become the first printed book. It was an invention that would signal the end of the tradition of manuscript production on vellum and herald the arrival of the mass-produced printed book on paper.

Tim O’Neill is a calligrapher and historian and author of The Irish hand: scribes and their manuscripts from the earliest times (Cork University Press, 2014).