By Gerry Finnegan

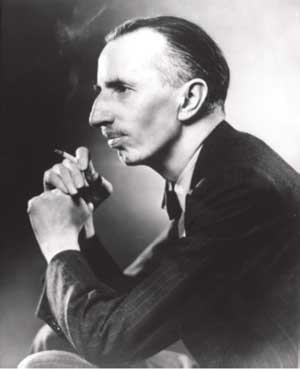

Membership of the League of Nations was the first major foreign policy objective of the new Irish Free State, achieved 100 years ago on 10 September 1923. With it came membership of the International Labour Organisation (ILO). An important yet unheralded figure in this achievement was Waterford-born Edward Joseph Phelan (1888–1967), head of the ILO’s Diplomatic Division.

In 1895, at the age of seven, Phelan accompanied his family in their move to Liverpool, where he was to complete his education at Liverpool University. In 1914 he joined the British civil service in the new Ministry of Labour. Shortly thereafter the First World War broke out. Once hostilities ended in 1918, the British government formed its team to participate in the Paris peace conference. Two worker-led revolutions in Russia in 1917 had alerted the victorious Allies to the demands of workers in their own countries. Furthermore, in the post-war period the labour market was flooded with unemployed workers—demobbed soldiers, released prisoners of war and those who had been engaged in supplying the war effort. Consequently, the peace conference accorded high priority to the plight of workers.

FORMATION OF THE ILO

Phelan was on the British delegation in Paris and was appointed secretary to the Commission on International Labour Legislation. The Commission’s discussions relating to the ILO were kept separate from those leading to the formation of the League of Nations. Although the ILO had a strong degree of autonomy, it was to depend on the League for its funding.

The creation of the ILO in April 1919 was a quick and tangible outcome of the complex negotiations at the peace conference, and a concrete result aimed at satisfying organised labour. Phelan was seconded from the British Labour Ministry to lead the formation of the organisation out of its temporary base in London. The ILO’s pace of progress led to its holding its first International Labour Conference in Washington in October/November 1919, at which several International Labour conventions were adopted.

The conference asserted the ILO’s autonomy from the League and took the bold decision to admit Germany and Austria as members although they were not yet members of the League. The Treaty of Versailles determined that members of the League automatically became members of the ILO, but not the other way around. The ILO’s constitution empowered it to admit any country as a member, and this applied again in 1934 when it admitted the USA, which never joined the League. The conference confirmed the French politician Albert Thomas as its first director with effect from 1 January 1920.

Director Thomas appointed Edward Phelan head of the Diplomatic Division—the ‘first international civil servant’. In 1920 the ILO’s governing body voted to base its headquarters in Geneva, alongside the League, and Phelan had responsibility for its transfer from London to Geneva. Under the leadership of Thomas, the ILO adopted the mantra of ‘social justice’ as its core strategy, and it remains central to the organisation 100 years later.

LONG-STANDING INTEREST IN IRISH AFFAIRS

During his years in Liverpool, Phelan had followed the fortunes of the Home Rule movement and the local Irish Parliamentary Party MP, T.P. O’Connor, the solitary Irish nationalist MP elected to Westminster outside Ireland. As an Irish-born British civil servant, Phelan kept a watchful eye on events in Ireland throughout the war—events leading to the Easter Rising, the War of Independence, the Civil War and the creation of the Irish Free State.

In 1918 the elected Sinn Féin MPs refused to take their seats at Westminster and formed their own assembly in Dublin, Dáil Éireann. Cork-born Michael MacWhite had been appointed to lead Sinn Féin’s delegation to the Paris peace conference, where they strove to present the case for Irish independence from Britain. They received no support from US President Woodrow Wilson and, predictably, none from Great Britain. Once the Irish Free State came into existence towards the end of 1921, MacWhite was transferred to Bern, Switzerland, as Ireland’s representative responsible for preparing the case for joining the League of Nations.

IMPRESSES SINN FÉIN’S MICHAEL McWHITE

MacWhite paid a courtesy call to the ILO in Geneva, where Director Thomas introduced him to Edward Phelan. MacWhite was impressed by Phelan and reported to Dublin that he had met ‘an Irishman of outstanding ability in the person of Edward Phelan’, acknowledging the possibility of having in him a valuable ally. This was Phelan’s first contact with anyone connected to the new Irish administration.

In January 1922 a Sinn Féin delegation travelled to Paris to participate in the Irish Race Congress, organised by the Irish Republican Association of South Africa. Phelan accompanied Thomas to Paris, where they met the Irish delegation with the intention of encouraging Ireland’s membership of the ILO. This was Phelan’s first opportunity to meet Ireland’s new political leadership and he presented his informal credentials as an advocate for Ireland, assuring the Sinn Féin delegation of his support in their aim of joining the League and the ILO.

The meeting in Paris invigorated Phelan. It was a homecoming for him emotionally, through reconnection with his Irishness, and politically, by providing opportunities to contribute to the advancement of the new Irish nation internationally, albeit from a distance. Phelan subsequently opened lines of communication with members of the delegation and officials in the Department of External Affairs, as well as with the president of the Executive Council, W.T. Cosgrave. His subsequent election as president of the International Club of Geneva further enhanced his role among Geneva’s diplomatic community. MacWhite was impressed with Phelan’s electoral success, prompting him to inform Dublin that ‘Our friend Mr Phelan has been unanimously elected as [the Club’s] first President—a fact that attests to his popularity and standing in this country’. Phelan was a relative veteran among the new breed of officials at the hub of international diplomacy and a valuable ally for the Irish Free State.

AN INTERNATIONAL CIVIL SERVANT WHO HAPPENED TO BE IRISH

Phelan bombarded his Irish contacts with information relating to membership of the League, urging them to make application at the League’s next Assembly in September 1922. Although his advocacy for Ireland was aimed at bringing a new member state into the ILO, there were times when he crossed red lines, his strident efforts were excessive and created problems for his close associate, MacWhite, who was Ireland’s official channel of communication with the League and the ILO. Phelan was an international civil servant who happened to be Irish, with no formal standing in the state’s administration. While his direct contacts with Dublin had undoubtedly been helpful and appreciated by the Irish administration, they were often conducted over the head of MacWhite, who was obliged to confirm to Dublin that Phelan was acting in a personal capacity.

The Provisional Government did not apply for League membership in 1922, as it awaited ratification of its new constitution. Undaunted, Phelan switched his approach to promoting membership of the ILO—‘an autonomous official organisation of 55 states … the activities [of which] are non-political’, and with a less complicated membership procedure. He reminded them that Germany and Austria had been admitted to the ILO, although they were not members of the League.

LEAGUE AND ILO MEMBERSHIP

Following Ireland’s joining of the League (and automatically the ILO) on 10 September 1923, Minister for Education Eoin MacNeill wrote: ‘I must put on record the invaluable assistance that our Delegation received throughout the session from Mr Edward Phelan. […] He was always watchful for the advantage of Ireland, and his advice never failed us and never misled us.’

Membership of the ILO, more so than the League, provided tangible evidence of Ireland’s separate identity and independence from Britain. When Ireland registered its adoption of ILO conventions, the documentation was communicated directly to the League for onward transmission to the ILO. It did not go through London, as Britain would have expected. Phelan would have been instrumental in the ILO’s adopting this bypass procedure. He was openly and determinedly Irish and was among the first to seek Irish citizenship. He was suspicious and ever vigilant of Britain’s intentions and motives in relation to the Irish Free State.

Membership of the League of Nations provided assurance to the fledgling state of its international status as an entity separate from the United Kingdom. Ireland sought further reassurance by registering the Anglo-Irish Treaty (1921) as an international legal instrument with the League. Britain opposed this procedure, as it viewed the Treaty as an internal arrangement between two members of the British colonial ‘family’. This was not a British decision, however, and the Treaty was successfully registered at the League on 11 July 1924. Once again, Phelan—the international diplomat—played a significant background role in advising the Irish government. There were occasions, however, when Phelan’s advice was not welcome, and even deemed to be ‘wrong’, leading to the occasional reprimand.

Phelan engaged in scholarly writing, submitting three learned articles to the Irish quarterly review Studies. The first of these, ‘The International Labour Organisation—its ideals and results’ (Vol. 14, 1925), provided contemporary commentary on the origins of the ILO and the League of Nations. The following year, Phelan penned a two-part article on ‘Ireland and the International Labour Organisation’ (Vol. 15, 1926), the first of which dealt with Ireland’s role as a full-fledged member during its first years with the ILO; the second part illustrated how Ireland’s membership of the ILO confirmed its autonomy and enhanced its status in international diplomacy. These articles demonstrate Edward Phelan’s role in championing Ireland’s nationhood—far beyond his status as a senior official in the ILO.

Gerry Finnegan is a retired official of the ILO (1988–2010).

Further reading

G. Finnegan, Edward Phelan and the ILO: the life and views of an international social actor (Geneva, 2009).

G. Finnegan, The Irish influence: building the League of Nations and the International Labour Organization (Belfast, 2023).