By Daniel Mulhall

I have often wondered where Arthur Griffith got the idea for his influential political tract The resurrection of Hungary, published in 1904. It led to the setting up the following year of the first Sinn Féin party, dubbed ‘the green Hungarian band’ by the caustic pen of Leader editor D.P. Moran. Griffith proposed a dual monarchy for Britain and Ireland along the lines of the Austro-Hungarian example.

THE HISTORY OF HUNGARY AND THE MAGYARS (1853)

In the ‘Cyclops’ episode of Ulysses, James Joyce, with tongue in cheek, has John Wyse Nolan claim that Leopold Bloom had given Griffith his Hungarian idea. Griffith may have taken inspiration from another Irish writer, Edwin Lawrence Godkin, whose book The history of Hungary and the Magyars was published in 1853. That work was highly sympathetic to Hungarian aspirations and deeply hostile to Austria and its ultra-conservative foreign minister, Prince Metternich, ‘one of the ablest high priests that had ever ministered at the altar of absolutism’, as Godkin memorably described him. Godkin added that Metternich ‘worshipped facts—he hated opinions. He was constantly occupied in building fortifications between them.’ In his contribution to the Handbook of Home Rule (1887), a publication Griffith could well have read, Godkin cited the Austro-Hungarian example from 1867 as a way of peacefully sundering a union. The creation of the dual monarchy had, he wrote, converted Hungary from ‘a discontented and rebellious province’ into ‘a loyal and satisfied’ part of the Habsburg Empire.

Godkin’s surname would have been well known in nineteenth-century nationalist Ireland, for his father, Revd James Godkin (1806–79), a Protestant minister, had been ousted from his vicarage when it became known that he was a supporter of O’Connell’s Repeal movement and a friend of Young Ireland leaders Thomas Davis and Charles Gavan Duffy. James Godkin moved into journalism, editing the Dublin Daily Express for ten years and publishing several books on Irish topics, including The Land War in Ireland (1870), which supported Gladstone’s land bill and also cited Hungary as a model for Ireland.

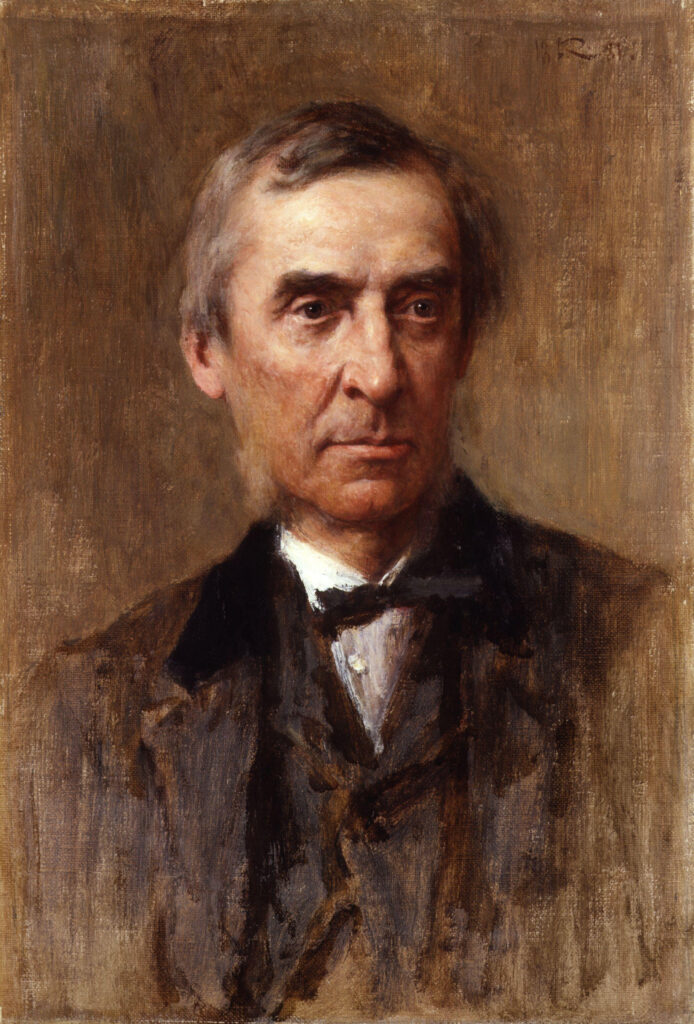

WAR CORRESPONDENT

E.L. Godkin (as he became known) was born in County Wicklow in 1831 and studied at Queen’s, Belfast, where, influenced by exposure to the writings of John Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham, he embraced the classic utilitarian liberalism of that era. He covered the Crimean War as a correspondent for London’s Daily News. While far less renowned than his countryman William Howard Russell of the London Times, Godkin’s dispatches gave ample evidence of the quality of his mind and the power of his writing. His focus was on the gore rather than the glory of war. Seeing the bodies of Russian soldiers strewn across an old cemetery, he wrote that they could be mistaken for ‘the peaceable tenants of the tombs’ who had risen ‘to ask the cause of the wild tumult which raged above their abodes’.

IN AMERICA

On his return from Crimea, Godkin briefly edited the Northern Whig in Belfast before emigrating in 1856 to America, where he married Elizabeth Foote, a cousin of Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s cabin. Following an extended tour of America’s southern states, Godkin expressed his opposition to slavery and supported the Union cause during the Civil War, which he covered for London’s Daily News.

In 1865 he became the editor and later proprietor of the Nation, a weekly publication whose title may have been inspired by the Young Ireland paper of the same name. Godkin’s Nation, with its high-minded reformism, was dubbed ‘the weekly day of judgement’. In 1881 the Nation merged with the New York Evening Post and, as editor-in-chief, E.L. Godkin became one of the most influential commentators of America’s Gilded Age, of whose excesses and failings he became a stringent critic.

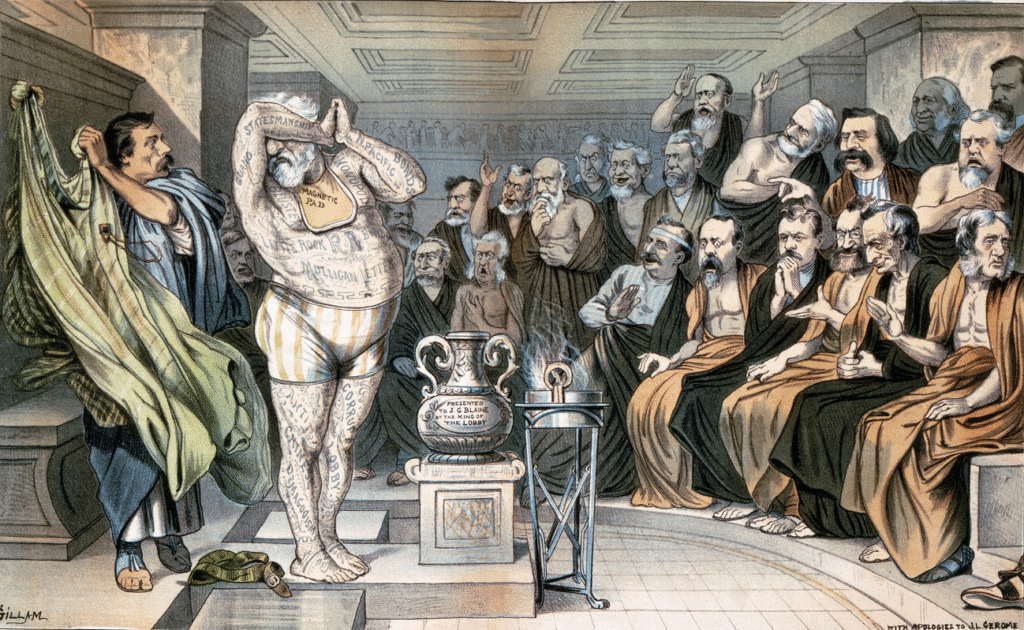

BEING A MUGWUMP

Godkin was a leading voice among the ‘Mugwumps’, reforming liberals who abandoned the Republican Party during the 1884 presidential election because of their aversion to the scandal-ridden Republican candidate, James Blaine. Blaine also blotted his copybook with many voters by describing the Democrats as the party of ‘Rum, Romanism and Rebellion’ and on account of his reliance on millionaire backers.

‘Mugwump’ support helped to elect Grover Cleveland, the first Democrat to occupy the White House since the Civil War, although Cleveland too had his problems, having fathered a child with a woman who was not his wife. Mark Twain rose to his defence, spiritedly dismissing arguments against ‘a bachelor’s fitness for President because he has had private intercourse with a consenting widow’. Aside from Donald Trump, Cleveland is the only US president to win two non-consecutive terms, having lost his first bid for re-election in 1888.

SUPPORTER OF HOME RULE FOR IRELAND

Godkin never lost his interest in Irish affairs and was an opponent of coercion, which he saw as ineffective. Coercion bills, he thought, were passed simply to satisfy English pride. Writing to the leading Gladstonian Liberal, James Bryce, in 1887, Godkin described one such bill as a reflection of ‘the worst and most unbearable side of the English character’ and of an unwillingness ‘to please anybody who cannot lick you’. He described Dublin Castle as a foreign stronghold in Ireland and believed that communities that managed their own affairs were more likely to be orderly.

Although Godkin saw himself as Irish by birth but of English heritage, he argued that the English people ought to take upon themselves ‘their share of the horrible burdens of Irish history’. He was a strong supporter of Home Rule, drawing on his American experience to answer conservative objections to Gladstone’s first Home Rule Bill (1886). In particular, he took aim at those who argued that recourse to agrarian violence during the Land War meant that Ireland was unfit for self-government, pointing to the many outbreaks of violence in American history which, however horrible they may have been, did not negate US democracy.

Godkin also took to task two arch-critics of Irish nationalism, James Anthony Froude and Goldwin Smith, describing the former’s history of Ireland as ‘a most discreditable performance’ and the latter as a purveyor of ‘Hibernophobic fury’. Godkin was gratified to be present in the House of Commons in 1893 to witness the passage of the second Home Rule Bill.

NOT A TYPICAL NINETEENTH-CENTURY IRISH AMERICAN

It would be wrong to assume that Godkin was a classic nineteenth-century Irish American. Far from it, but he was acutely aware of the political clout wielded by the Irish in America and counselled his readers in Britain not to expect anti-British sentiment in the US to end anytime soon. Many Americans would, he warned, be quite pleased to see American Fenians ruffling Britain’s feathers.

Irish influence in New York politics became a prime target of Godkin’s reformist ire. He engaged in an extended war of words against the bosses of the Irish-dominated Tammany Hall. The Nation regarded Tammany as an ‘extraordinary menace to both liberty and property’, two pillars of Godkin’s political philosophy.

Although he shared the initial optimism of the post-Civil War period, Godkin’s world-view darkened as the century entered its closing quarter. In particular, he became sceptical about popular democracy in a society like late nineteenth-century America, with increasing numbers of poor, ill-educated voters. He deemed municipal democracy a ‘ridiculous anachronism’. In the 1870s he took part in a commission that recommended property requirements for voters that would have disenfranchised two thirds of New York City’s voters, many of them Irish immigrants. Because of his view that democracy could only function properly in small homogeneous communities, he fretted that in America it had produced corruption and carried a risk of anarchy.

GLOOMY ABOUT GILDED AGE AMERICA

By the end of the century Godkin had become, in the view of one observer, ‘a praiser of past times and a disparager of the present’. With his increasingly conservative version of liberalism, his opposition to US expansionism and his belief in a gold-based currency, he was out of step with the buoyant spirit of that age. In the words of one historian, his posture ‘captured liberalism’s precarious intellectual condition and its rising association with wealth and privilege’. Now where else have I come across that idea? Teddy Roosevelt, the rising political star of fin-de-siècle America, had no time for Godkin. A man with sharp rhetorical elbows, Roosevelt described Godkin as ‘maliciously untruthful’ and ‘utterly untrustworthy’. Ouch!

Godkin’s high expectations for America, which had buoyed him when he arrived there in mid-century, dissipated as the years passed. By the time he departed at the century’s end, he felt a need to look elsewhere for a source of hope for humanity. Gripped by a gloomy despair about the direction of American politics, he returned to Europe and settled in Devon, where he died in 1902. His name lives on at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, which still hosts a prestigious annual public lecture established at the time of Godkin’s death by the philosopher William James, brother of novelist Henry James.

OUT OF TOUCH WITH THE SPIRIT OF A NEW AGE

Godkin’s career provides an illustration of how once-fresh political philosophies wane as socio-economic developments sideline them. As he got older, Godkin exhibited more and more of a narrowly conservative outlook and tended, in the view of one contemporary, to view democratic politics as ‘a stage for an unending morality play’ that he feared would result in an immoral denouement. Political developments in the years after his death defied his deep pessimism.

Democratic political systems often produce trends and outcomes that can bewilder even the cleverest and most serious of observers. Thus Godkin, for all of his literary/analytical abilities, found himself marooned in a fin-de-siècle America that was torn between the populism of William Jennings Bryan and the reformist zeal of Teddy Roosevelt. The whiggish north-eastern élite to which Godkin belonged had had its day. More robust versions of political activity were on the rise. Instead of the democratic anarchy that Godkin feared, in America the opening decades of the twentieth century spawned, in successive waves, progressivism, Wilsonian liberalism and a New Deal under the patrician Franklin Roosevelt. The political world can be full of surprises.

Daniel Mulhall is the author of Pilgrim soul: W.B. Yeats and the Ireland of his time (New Island Books, 2023).

Further reading

W.M. Armstrong, The Gilded Age letters of E.L. Godkin (Albany, 1974).

R. White, The republic for which it stands: the United States during Reconstruction and the Gilded Age, 1865–1896 (New York, 2017).